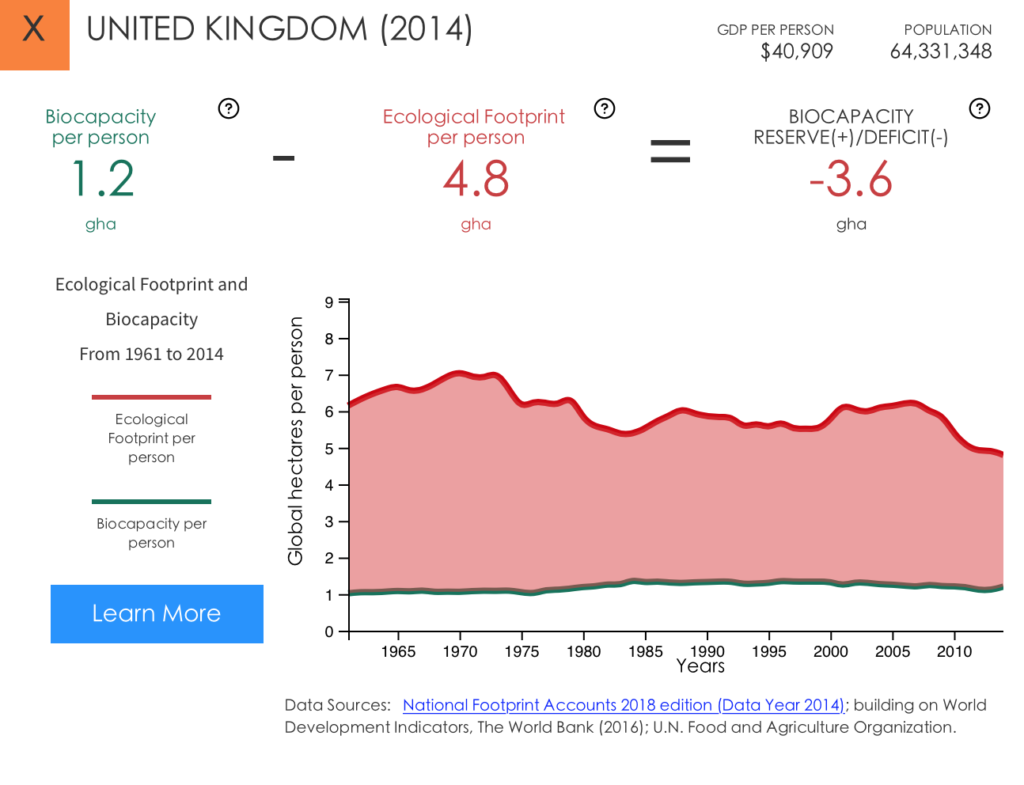

This is a screenshot from the Global Footprint Network. It shows a reduction in the UK’s ecological footprint. This is good news, right? Well, yes, the footprint is getting smaller, but it is exactly 4x the country’s biocapacity, leaving a significant ecological deficit.

An ecological deficit occurs when the Ecological Footprint of a population exceeds the biocapacity of the area available to that population. A national ecological deficit means that the nation is importing biocapacity through trade, liquidating national ecological assets or emitting carbon dioxide waste into the atmosphere. An ecological reserve exists when the biocapacity of a region exceeds its population’s Ecological Footprint.

I’m sharing these data because Earth Overshoot Day has just recalculated the date when “humanity’s demand for ecological resources and services in a given year exceeds what Earth can regenerate in that year” (link to quote). That date is now August 1st (back in the 1970s it was December 31st). Another way of putting it, and the way that Earth Overshoot Day likes to put it, is that we need 1.7 planets to support humanity’s demands on Earth’s ecosystems.

I say humanity, but some populations consume more than others. Per capita, Iceland, Norway and Bahrain (the highest consumers of electricity in 2016) consume more than Haiti, South Sudan and Niger (the lowest). Furthermore, The World Resources Institute have put together an interactive map of the globe so that you can see which countries emit the most CO2 over time. And it’s also important to point out that most of the heaviest emitters are not human at all, with one study suggesting that just 90 companies were responsible for two-thirds of all global CO2 emissions.

Earth Overshoot Day was reported in the Guardian a few days ago. It makes for the kind of depressing reading we’re becoming all-too accustomed to these days. But what caught the eye of some observers was a, perhaps throwaway, claim by the reports author Jonathan Watts:

The situation is reversible. Research by the group indicates political action is far more effective than individual choices. It notes, for example, that replacing 50% of meat consumption with a vegetarian diet would push back the overshoot date by five days.

It’s worth pointing out that this isn’t Watts’ best piece. It’s quite sloppy to be honest. For one, the research group doesn’t make this claim, and if it did it would contradict pretty much all of its subsequent analysis (all of the recommendations that flow from the group’s data are aimed at individual behaviour changes – ‘streamline your wardrobe’, ‘start a population conversation’, ‘travel with eco-sensibility’, etc). For another, individual choice and political action are not mutually exclusive. And, finally, the link to the 50% claim about switching from a meat to a vegetarian diet actually takes you to a different study reported in the Guardian in May 2018. But never mind that.

The distinction, wrong as it is, begs the question: What should we do about global warming? There have been various suggestions historically, and plenty on the table today. Perhaps the hardest thing to do, but also the most important, is to shift a gear from doing nothing to doing something. If you read little more than the Introduction to Naomi Klein’s fantastic book This Changes Everything, then at least you will have read her highly personal account of despair – how she would see something beautiful in nature but then immediately interpret it in apocalyptic terms. I’ve caught myself doing that this summer; maybe you have too? Klein’s response to this is honest and empowering:

“When fear like that used to creep through my armour of climate change denial, I would do my utmost to stuff it away, change the channel, click past it. Now I try to feel it…

Next, use it. Fear is a survival response. Fear makes us run, it makes us leap, it can make us act superhuman. But we need somewhere to run to. Without that, the fear is only paralysing. So the real trick, the only hope, really, is to allow the terror of an unlovable future to be balanced and soothed by the prospect of building something much better…

It’s too late to stop climate change from coming; it’s already here, and increasingly brutal disasters are headed our way no matter what. But it’s not too late to avert the worst, and there is still time to change ourselves so that we are far less brutal to one another when those disasters strike.” p28

Having conquered our fears and decided to act, there are things we can do in the immediate term. Next hardest: start talking about global warming like it’s actually an existential crisis and not just a minor inconvenience. This idea has been percolating global health discourse since Costello and Watts urged us all “to shout from the rooftops that climate change is a health problem”. That was five years ago – do you hear any shouting? No, well there’s plenty to shout about, as the PLOS Collections special series on climate change and health makes abundantly clear: sewage from storm water, heat-related mortality trends (see extract from the New York Times article below), wild fires, women’s health, ozone-related acute excess mortality, nutritional deficiencies, reduced cognitive functioning, the list of health-related impacts of global warming are without limit it seems.

“She had traveled for 26 hours in a hot oven of a bus to visit her husband, a migrant worker here in the Indian capital. By the time she got here, the city was an oven, too: 111 degrees Fahrenheit by lunchtime, and Rehmati was in an emergency room. The doctor, Reena Yadav, didn’t know exactly what had made Rehmati sick, but it was clearly linked to the heat. Dr. Yadav suspected dehydration, possibly aggravated by fasting during Ramadan. Or it could have been food poisoning, common in summer because food spoils quickly”.

(Somini Sengupta, In India, Summer Heat May Soon Be Literally Unbearable)

But it took an article in Climate Home News – My baby can’t sleep from heat, why aren’t we talking about climate change? – to hit a nerve with parents. The sound of collective pennies dropping echoed around social media. This is a good thing. Indeed, as Woodworth and Griffin’s book Unprecedented Climate Mobilisation argues, talking about climate change and global warming is at the heart of mobilisation (an eBook copy will cost you £7, which is money very well spent – 2 cups of coffee).

The problem is that the media should be taking the lead in this conversation, but it’s not – quite the opposite in fact. In a chapter called Media Leadership is Essential, Woodworth and Griffin provide a list of things that corporate media should stop doing, a list that includes ignoring “the connection to climate change while reporting extreme weather events” (p61). Which is precisely what the UK’s BBC has been doing for years, and continues to do in the face of a sustained heatwave. This is unacceptable and an abrogation of the Corporation’s responsibilities detailed in its Royal Charter.

Ok, so now we’re talking. What’s next? Klein again: “Well, we do what we can. And what we can do…is to consume less, right away”. On its own, these kind of small-scale, individual behaviour changes – of the kind described on the Earth Overshoot Day pages – won’t make much difference without complementary, large-scale “comprehensive policies and programs that make low-carbon choice easy and convenient for everyone” and which, most of all, are fair (pp90-91). Klein’s book is full of examples of action, so just get a copy, read it, and be inspired.

Meanwhile, you will have noticed that there is a growing, global, climate litigation movement. Plan B for example, brought the UK Government to Court for failing to set a safe climate target for 2050. It lost that battle last week but plans to pursue the case through appeal. Plan B’s response highlights the stark and bewildering disconnect between the reaction from established institutions (the Courts, the media, the Government) and what, frankly, you, I, the whole world and its cat, can see from our kitchen windows.

“As with other legal campaigns confronting powerful vested interests it takes time to break through, and time is not on our side. We’ll be doing everything possible to accelerate the process. Wildfires raging in the Arctic Circle must surely be a wake-up call”.

Across the Atlantic, efforts to hold fossil fuel companies financially accountable for the impact of climate change to major US cities (New York, San Francisco and Oakland) also stumbled. As with most assertive action these days, we have ‘the youth’ to thank for taking the lead, and so it is with litigation mobilisation. Take the Children’s Climate Lawsuit, for example, which – since 2015 – has sought to bring both Democrat and Republican government to account, accusing both “of perpetuating policies that favor a fossil-fuel based energy system and of failing to adequately regulate greenhouse gas emissions”. The case continues.

Feeling energetic? Court rooms not your thing? Well, get out there and start marching because… #ThisIsZeroHour. The BBC didn’t cover the march, but it was yet another expression of a youth movement whose time has come. This is the paradox anyone born this century now faces:

“As young people, we find ourselves in this really awkward place in history where we are going to be alive for the worst effects of

#climatechange, but we’re not old enough to make the decisions right at that tipping point where they need to be made”

If marching is your cup of tea, then make a note of the date – September 8th – and join the global day of action inspired by #RiseForClimate.

Marching in itself is an awesome spectacle, but if the kinds of policies that Klein talks about – radical, far-reaching, emissions-busting policies – are going to be passed, and quickly, then marches on their own will not be sufficient. Recall that movements such as #ThisIsZeroHour don’t necessarily have the ear of government even if they are a powerful expression of dissatisfaction with the status quo. We now know who – or what – does have that ear. According to a new study, the fossil fuel industry has spent $2 billion this century lobbying US Congress – an amount 10x that of environmental organisations. Add that to the fact that governments across a small section of the political spectrum are supporting development projects that take us in precisely the opposite direction to where we need to be going – I’m talking specifically about the UK’s cross-party support for a third runway at Heathrow airport but there are so many other examples – and it is unsurprising to find many people looking for more direct action.

Perhaps the best example of direct action across the UK, and globally, is the anti-fracking movement. Adam Vaughan’s comprehensive overview of anti-fracking protest in the UK notes that “The past 12 months [i.e. all of 2017] have not been kind to the embryonic industry” and public support for this dirty, polluting industry has fallen to a record low. Direct action – blockading entrances to sites, physically chaining oneself to the floor to deny heavy plant access – works in a way that marches do not. That is not to say that the latter don’t have a place in political action; clearly they do. But, as Roger Hallam argues, governments can ignore marches, but they tend to take more notice of direct action (you can watch one of his ppt-free lectures here). Arrests and, better still, imprisonment, is – in Hallam’s opinion – the most effective act a person can do if they want to effect a change in policy (think Freedom Riders during the civil rights protests in the U.S; The Ploughshares Movement actions to disable Hawk fighter jets; or the recent coordinated hunger strikes and planned direct action by the social movement Rising Up! as a response to global warming).

So, to return to the distinction that prompted this post – political action or individual choice – and whether one is more effective than the other in responding to global warming, I think it’s a false distinction. The challenge facing all of us, Naomi Klein tells us, is not to prevent global warming – it’s too late for that – but to avert the worst of it. That requires an initial, individual choice: to decide to do something, or not; to act, or not act. If you choose the former, congratulations, you have evolved into a political animal.

Andrew

The Guardian reported yesterday – 24th July – that UK Energy Minister Claire Perry has issued a permit to Cuadrilla to start fracking in Lancashire, at the Preston New Road site.

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/jul/24/cuadrilla-gets-go-ahead-to-start-fracking-at-lancashire-site

Respect to the six protestors who locked themselves to the entrance to the site.

https://drillordrop.com/2018/07/24/first-lock-on-challenge-to-cuadrilla-fracking-protest-injunction/

Perry said: “Our world-class regulations will ensure that shale exploration will maintain robust environmental standards and meet the expectations of local communities”.

George Monbiot had a slightly different take, tweeting this morning: “As the world burns, the government uses the last day of parliamentary business to sneak through approval of #fracking in Lancashire, against massive public resistance. This government does not work for us. It works for oligarchic capital”. https://twitter.com/GeorgeMonbiot/status/1022032796636930048

On the plus side, Plan B have filed their appeal wit the Court of Appeal – the UK Government has 14 days to respond from today (26th July) https://planb.earth/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Plan-B-v-BEIS-Skeleton-Permission-Appeal-SEALED.pdf

Here is some further reading on hydraulic fracturing and health:

Elizabeth Reap’s study – ‘The risk of hydraulic fracturing on public health in the UK and the UK’s fracking legislation’: https://enveurope.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s12302-015-0059-0

MEDACT’s report – ‘Health and Fracking’: https://www.medact.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/medact_fracking-report_WEB3.pdf

Update – Guardian – 5th August 2018 ‘Climate change battles are increasingly being fought, and won, in court’ reports on successful court case in S.Africa that has prevented the SA Government from building a new coal-fired power station https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/mar/08/how-climate-change-battles-are-increasingly-being-fought-and-won-in-court