“Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. This is the principle on which I bring up my own children, and this is the principle on which I bring up these children. Stick to Facts, sir!” (Dickens, Hard Times. p1.)

Hans Rosling died of pancreatic cancer in 2017. It was a sad day for those of us working in global health. Who doesn’t remember those funky computer-generated visuals designed by his son Ola and daughter-in-law Anna Rosling Rönnlund? You don’t? Then you have to watch this presentation Rosling gave in 2007 (now viewed by 2.83m people).

Rosling was every bit the showman. In his book Factfulness, he confesses that his childhood dream was “to become a circus artist”, and there is an x-ray in the book of him sword swallowing (who knew!). It wasn’t just those floaty spheres that could amaze you. Who else would even think of using hotel crockery to demonstrate global population growth? (see from 4m 24s)

No surprise then that Rosling is considered to have been one of the great global health educators: his public lectures were entertaining and his enthusiasm was infectious. But I would argue that his pedagogy left a lot to be desired.

The problem I have with Rosling, as my reference to Dickens’ character Thomas Gradgrind unsubtly indicates, is his obsession with facts. Apparently, there are facts in the world of which most of us are blissfully unaware. And if we were aware of them, we would have a much less pessimistic view of global health.

Rosling liked to test his audience with questions like: What is the life expectancy of the world today? Is it 50, 60 or 70 years? Invariably, the audience would guess wrong; worse, they would make an un-educated guess and skew the results such that a bunch of chimpanzees would have fared better. Everyone would laugh at their collective ignorance. I’ve tried this question on my own students, and sure enough they guessed wrong.

Personally, I don’t find the revelation particularly surprising. So what that most people have no idea that global life expectancy is 70? I only knew because I watched one of Rosling’s videos. Why would I know otherwise? Generally, I don’t retain this kind of information easily. And if I’m unsure, I just look it up on DuckDuckGo.

I’ll return to the ‘facts’ in a minute. First, take a look at the sub-heading of the title of his book Factfulness : ‘Ten reasons we’re wrong about the world – and why things are better than you think’. Rosling was being polite – what he means is ‘ten reasons why you’re wrong‘. There is no self-doubt in his analysis. But in my humble opinion no teacher worth their salt should start from the presumption that you are wrong and they are right. But that was essentially Rosling’s starting point. He had a handle on ‘the truth’ and wanted to put you right.

While writing this post, I had in the back of my mind that classic book on education by Paulo Freire The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, so I had a re-read of Ch2. Here, Freire describes the narrative character of teaching. The ‘task’ of the teacher, Freire argues, is categorically not to fill the student with the contents of his narration, like depositing money into a bank. This is because it leads “the students to memorise mechanically the narrated content. Worse yet, it turns them into ‘containers’, into ‘receptacles’ to be filled by the teacher”. And it results in entirely inappropriate measures of educational success: “The more completely she fills the receptacles, the better a teacher she is” (p52-53).

By contrast, a liberatory approach to teaching “must abandon the educational goal of deposit making and replace it with the posing of the problems of human beings in their relations with the world…The students – no longer docile listeners – are now critical co-investigators in dialogue with the teacher. The teacher presents the material to the students for their consideration, and reconsiders her earlier considerations as the students express their own” (p61-62). In other words, critical reflection.

Humility, not certainty, in the face of a complex world. Things are never as straight forward as you think, and the skill one hopes a student of global health will hone is their critical faculty. ‘Facts’ don’t get you very far in that pursuit. “How can so many people be so wrong about so much?” asks Rosling in the Introduction to his book (p10). Well, consider the following question: “In the last 20 years, the proportion of the world population living in extreme poverty has a) almost doubled, b) remained more or less the same, c) almost halved?

Did you answer C? If you did, congratulations you’ve learned absolutely nothing! The correct answer, of course, is not A or B or C; the correct answer is ‘what do you mean by extreme poverty’? Anybody who sat through one of Rosling’s presentations will have come away thinking that the correct answer was C. None will have come away doubting the Word Bank’s definition of extreme poverty on which this ‘fact’ is based, and which allows one to proclaim its rapid decline.

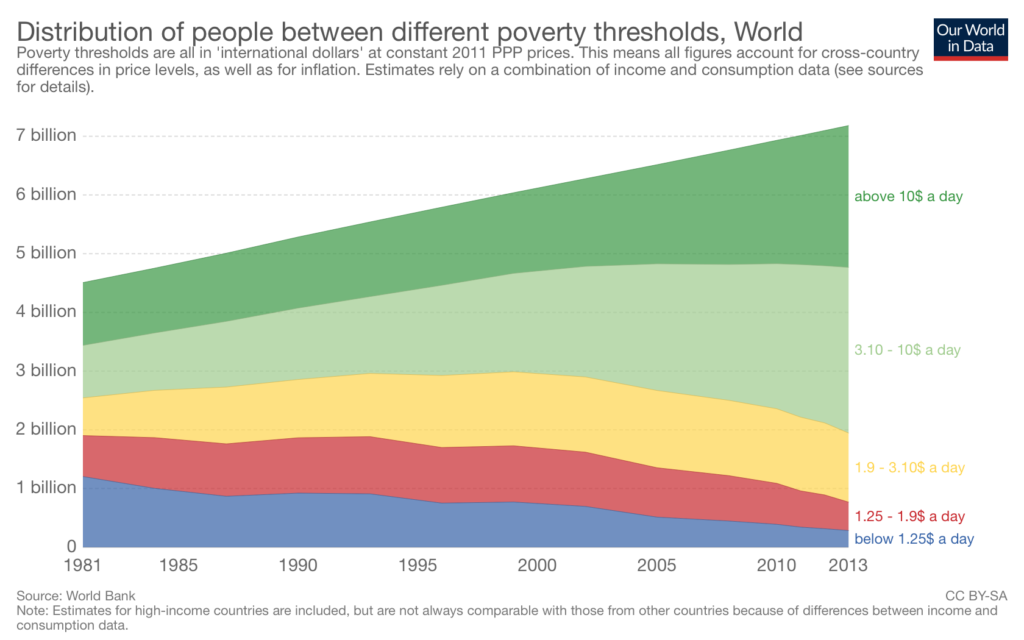

Take a look at the graph at the top of this post. It comes from a post by Diana Beltekian and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina that compares the total number of the world’s population against a range of different poverty measures, ranging from below $1.25 to above $10 per day. You’ll notice that the number of people living within the $3-10 per day band has increased in the last 4 decades from 894m in 1981 to 2.82bn in 2013.

Notice too the difference in the measures of data between this graph and Rosling’s poverty question: total numbers vs proportions. Also note that there is a range of poverty measures from which you can choose, all of which you might well want to argue are extreme! Ironically, the one measure of extreme poverty that Rosling chose to focus on is the most problematic. As Jason Hickel points out in a recent post, living on $1.8 a day is not even enough to buy you the calories you need to avoid starvation. In that respect, $1.8 is way beyond ‘extreme’ – it is an immoral measure – horrific even. But Rosling doesn’t tell you these ‘facts’.

To return to Gradgrind: “You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them”. Dickens knew this was a pile of horseshit, hence the absurd caricature he sketched in his book – a book first and foremost about poverty. It is a critical appreciation of facts that will best serve those wishing to learn about global health. Facts do exist in the world, of course (while I consider myself to be a constructivist, for me it’s not ‘ideas all the way down’). You can add up the ages of population x , and divide that number by the total population to derive an average age at point y. But, ultimately, all that that gives you is a number. And numbers out of context are a very dangerous thing.

To return to Freire: if you believe that a teacher teaches and the students are taught; if you presume to know everything and the students know nothing; or prefer to talk while the students listen (meekly); or you choose and the students comply; or if you become the subject of the learning process and the students the objects. If you do or think any of these things, then I’m afraid you’ve confused the authority of knowledge with the authority of your profession. And therein lies the road to oppression.

Andrew