A paper by Clare Wenham and Sara Davies has just been published in Health Economics, Policy and Law. ‘What’s the ideal World Health Organization(WHO)?’ is a provocative essay about WHO’s mandate, scope, governance, structure, funding and domestic/international responsibilities/activities. Wenham and Davies are global health/IR experts of some repute: Wenham was Rapporteur of the Review Committee regarding amendments to the International Health Regulations whose Final Report was published in February; Davies’ book Global Politics of Health remains a must-read on the topic. If anyone knows what an ideal WHO should look like, it is likely to be these authors. The intention of their essay is to generate discussion, so I guess we might as well discuss it.

The short version

The authors argument could be summarised thus:

- WHO is struggling to fill a gap between what it was created to do and what it can get its member states to do;

- Furthermore, it faces a paradox: the very states funding WHO are acting in ways that undermine the Organisation’s health goals;

- This ‘tension’ may be unresolvable;

- The solution is to identify WHO’s strengths and weaknesses, measured in terms of those activities that attract the most compliance from states;

- And reconstitute WHO’s mandate to focus on the former and letting go of the latter;

- This will allow WHO to excel by doing less;

- While that means that WHO does not need additional funding, funding reform would still be required.

My response could be summarised thus:

- The gap the authors identify is an inherent tension within state/International Organisation relations, but states are being particularly misguided in this case. It reflects a more serious, current challenge to multilateralism that must be resisted if international cooperation is going to endure. Wenham and Davies’ argument won’t help in this regard, and may even exacerbate the problem;

- The paradox the authors identify is also an inherent feature of state/International Organisation relations, but it is particularly grotesque in a health context;

- The tension is not unresolvable. States can learn to behave differently. Less abstractly, governments can behave differently although this is contingent on ideology. It’s important to remember that there are 194 governments represented at the World Health Assembly and they don’t all speak with one voice. We should be careful not to amplify the voices of the most powerful states and their governments. The WHO ‘we’ want therefore begs the question – who is ‘we’?

- The solution is NOT to structure a mandate around what states are prepared to support. This will: a) ensure that WHO further reflects powerful state interests; b) reduce WHO to host and technical adviser; c) this will impact negatively on its authority as it will be associate with a perceived loss of status; d) it will further weaken WHO’s significance as a global health actor;

- If we start messing around with WHO’s mandate, the Organisation is finished. It is likely to be a moot point though because there would be little appetite from states to do this. The correct approach would be to identify areas of work where WHO is weakest and support those areas financially so that it can improve them;

- Member states need to grow up, recognise the importance of multilateralism and start funding WHO like they mean it;

- It is important to remember that we are talking about minuscule amounts of money. Funding options should be framed in terms of health benefits (i.e. what could WHO do with 100%, 200%, 300%, etc. more money) rather than identifying efficiency savings (i.e. how can we squeeze the most value out of an underfunded organisation). When it comes to global health, we should be thinking big not thinking small.

The long version

Framing

Nobody likes to hear how well you’re doing, and the essay starts with predictably negative framing: “The World Health Organization (WHO) is tasked with the ‘attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health’, yet, it is widely struggling to meet this mandate, and COVID-19 has revealed significant limitations of the organisation”. If you only read the first sentence of the abstract, this is what you get: WHO = struggle + limitations. At the most general level, the frame reinforces the argument: WHO is really struggling > there are serious limitations > profound reform is necessary. If WHO is broadly doing ok (not great, but not terrible either) in meeting its mandate, and COVID-19 has revealed that WHO can just about manage under almost impossibly difficult circumstances, then there’s less of a reason to spend 5000 words arguing for fundamental reform. If I was writing a similar essay to this one, my first two sentences would be something like: “The World Health Organization (WHO) is tasked with the ‘attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health’. Surprisingly, given the circumstances, WHO managed to meet its mandate in many respects. COVID-19 has revealed that the Organization can manage a pandemic quite well, albeit with some important limitations”.

Who is we?

‘We’ crops up in various guises in the essay, but needs clarification. In the abstract, we read: “in this perspective we lay out the obstacles WHO face to become the WHO ‘we’ need”. If we’re going to talk about the WHO we need, then it’s important to be clear who ‘we’ are. “We” is rightly put in inverted commas to show that the authors recognise that it is contested, so that’s fine. But they then proceed to equate ‘we’ with the standard unit of analysis – the state – used by International Relations (IR) scholars. The authors cite Gostin’s 2020 article, presumably as inspiration for the ‘WHO we need’ phrase that the authors use, but it’s an odd choice. Gostin doesn’t write in his article about states but writes about “the world’s people”, and also emphasises that “Governments have the WHO they deserve”. Personally, I think it’s too abstract to answer the question ‘what’s the ideal WHO’ in terms of states. It requires us to believe that states have ‘agency’? Theoretically, they do, but as a matter of praxis it’s not ‘the state’ that makes decisions, it’s governments. So it feels less meaningful, practically, to talk of an ‘ideal WHO’ from a state perspective. On agency, see Braun et al’s Special Issue: Rethinking Agency in International Relations.

States aren’t the only actors that appear in the essay – civil society is given a big shout out (which is great) as is the private sector and IFIs like the World Bank. But this makes it hard to attribute agency. This is quite normal in IR writing. As Colin Wight observed: “attributions of agency can change, not only within theories, but also within the space of a sentence”. And so it is in Wenham and Davies’ essay. I think that if the question is “What’s the ideal WHO?”, then the answer is going to be different depending on whether the referent point for ‘we’ is states, governments or people. If the referent point is governments, then for sure you can argue what governments might consider to be an ideal WHO, although this would very much depend on the ideology of the particular government. But it’s also important to note that 194 governments represent their constituencies at WHO’s World Health Assembly, and they don’t all speak as one. Civil society organisations also don’t all speak as one, but these views should also be taken into account.

There’s a distinction to be made between the WHO we ‘need’, the WHO we ‘want’ and the WHO we ‘deserve’. These are quite different concepts requiring all manner of un-packing. Need, want and deserve again depend on the referent point. Here, we would do well to focus less on states and governments, and more on people or, in public health terms, ‘the population’ by which I mean the global population. Those who most ‘need’ a public health-oriented, socially conscious international organisation such as WHO generally have no voice. We will never hear what ‘they’ want because they are poorly represented at any level of society, and as a consequence of privilege we are likely oblivious to their ‘needs’.

Can we change the world or not?

It’s unlikely that agreement could ever be reached on what constitutes an ‘ideal’ WHO because it really depends, as does everything, on your understanding of what is/isn’t possible. For example, the authors argue: “It is possible that no reform can fix the structural problem that WHO faces as a technical international organisation: the tension between the best public health approach and the most politically salient offering”. I’m not sure why the tension is described as a “structural problem”: why are public health and politics being juxtaposed as structurally incompatible? Whatever the reason, it’s hard to imagine that the problem is completely resistant to reform.

For me, talk of structure inevitably leads to another of IR’s key concepts, the metaphysical ‘anarchy’. From a ‘neo’ Realist perspective, anarchy denotes an invisible, intangible structure within which states are compelled to act, guided by self-interest, and typically employing power to achieve their ends. Because of the ‘reality’ of anarchy, so the argument goes, some things are much more likely than not – cooperation, for example, or support for anything that might interfere with a state’s sovereignty (conditions attached to membership of an International Organisation, for example) are unlikely (or at least unlikely to occur unless specific conditions apply, and even then will be transient – here today, gone tomorrow). Thankfully, there is disagreement within the discipline about this assertion. Constructivist IR scholars disagree with Neo Realists, arguing that states don’t exist within a structural straight jacket but are capable of learning to behave differently within a social system. If that’s the case, then reform is possible.

Wenham and Davies refer to ‘political salience’. Salience refers to the importance attached to an issue by whoever is affected by it, usually voters. The phrase ‘political salience’ is, therefore, something of tautology. Wenham and Davies refer to it, although I’m not sure quite what they’re getting at: what’s a ‘politically salient offering’? Presumably, it’s an offering that is politically important? Often, salience is invoked as a reason to not do something (i.e., if something is perceived to be not salient, there’s no point doing it because, ‘realistically’, it’s not going to happen). Happily, history is replete with counter-examples of people who have made it their job to make something that isn’t politically ‘salient’, salient.

Ultimately, talk of ideals invites us to answer a fundamental question – can we change the world or not? Or in this case, can governments be encouraged to support WHO’s broad mandate, or not? Your answer to that will be deeply personal, reflecting who you are. Crucially, it is not determined by the existence of some hidden structure that makes change ‘unrealistic’.

Mind the gap!

For Wenham and Davies there is a gap “between what the WHO was created to do – offer technical guidance and best practice for a range of health concerns in ‘routine’ times and health emergencies – and what it is able to secure states to do in practice”. We’ll come to the question of what WHO was created to do below, but the gap is a legitimate problem: what use is/are International Organisations if some of their member states refuse to play ball? But is it too much to expect WHO to ‘secure’ states to act? How would it do that, exactly? Isn’t it the function of rules, laws and regulations to confer responsibility? The norm of international law – the International Health Regulations or even a Pandemic Treaty, for example – is a glue that helps hold the relationship between WHO and its member states together. It’s not the only factor at play, of course, but it’s quite significant in determining the extent to which WHO can function. If law is deficient, then isn’t that the problem, not WHO?

WHO’s mandate

What is WHO meant to do? Wenham and Davies aren’t the first to ask this question. Nearly a decade ago, Charles Clift wrote an influential Chatham House report What’s the World Health Organization For? which itself drew on analysis conducted a couple of decades prior to that led by Dean Jamison. Wenham and Davies’ analysis closely mirrors Clift’s and many of the arguments presented in these early studies are in evidence in Wenham and Davies’ essay. An important distinction is between ‘core’ and ‘supportive’ functions, with Jamison, Clift, Wenham and Davies all focusing attention on the need for WHO to concentrate on its ‘core’ functions – typically understood as the provision of global public goods. What should/shouldn’t constitute ‘core’ is not just contested in and of itself, though. For example, even if we agreed that ensuring global health security is a core function, we would still have to agree what ‘security’ meant.

Wenham and Davies are clear what WHO is not: “The mandate of WHO is as a technical and normative organisation…What it is not is an operational body”. But is that really true? Article 2 of WHO’s mandate lists 22 functions, some of which lend themselves to operational work. A paper just out by Gostin et al has a different take on this: “The world needs a global health leader that has the resources, authority, institutional credibility and evidence-based policies to effectively carry out its normative, technical and operational functions” (emphasis added). The ‘et al’ list of authors that contributed to this paper include such luminaries as Helen Clark, Bjorn Kummel, Benjamin Meir and K Srinath Reddy. So it’s not exactly a fringe view that WHO is an operational body. To be fair, Gostin et al are referring specifically to WHO’s emergency operations but, nevertheless, this is evidence that there is room to disagree about whether WHO is an ‘operational body’ or not. With climate change becoming an increasingly urgent global health threat, one wonders whether this is an area of future work where an Organisation such as WHO could or should have strengthened operational capacity?

And, anyway, why shouldn’t WHO be an operational body? Because it doesn’t have the resources. Hmm, ok, well, maybe we give it the resources it needs? But member states won’t do that. Which states? And do you know why? And if you know why, are you happy with the answers? It comes back to the question of the WHO ‘we’ want. Wenham and Davies put their argument thus: “Our point is that either the funding model designed in the 1940s is no longer fit for purpose for an increasingly operational body, or the activities of the organisation need to be reduced to fit the financing model”. OR the original funding model IS fit for purpose but has been corrupted (thanks to some ill-advised revisions to it in the 1980s) and needs to go back to how it was originally conceived. There’s no need to start messing around with WHO’s mandate when we could just fund WHO how we used to, ramp it up a bit and ensure that it is fully resourced. But Wenham and Davies don’t buy into that argument. Rather than do what is necessary but difficult (fully resource the broad WHO mandate), they would prefer to do what is expedient (cut WHO’s mandate to just those issues most ‘salient’ to its funders).

Paradox, paradox on the wall, who is the fairest of them all?

Wenham and Davies rightly point out a paradox at the heart of WHO, namely that it relies on funding from members whose actions directly contradict the good things that WHO is trying to do. The example they use is ensuring universal access to vaccine technology during a pandemic: “WHO has argued that free and universal access to vaccine technology is essential to end this pandemic; meanwhile, WHO depends upon funding from the very states that are preventing universal access and use of this technology”. But this paradox isn’t restricted to universal access, and it’s a paradox that any IO dependent on state funding has to deal with. The reason (and I’m still running with the authors’ ‘state’ terminology here) is because states do bad things as well as good things. Russia remains a member of WHO despite its unlawful and brutal attack on Ukraine; Uganda is a member despite its horrific anti-LGBTQ legislation; the UK is still a member despite its disgusting and illegal anti-migration legislation; China, the United States, Hungary, Indonesia, etc, etc., are all still members of WHO despite all the awful things they’ve done historically and in the present. States are brutal and have – during the lifetime of WHO – been led by some of the most evil creatures on the planet. And WHO accepts funding from all of them while attempting to secure the ‘highest possible level of health” for all peoples. For WHO, it comes with the job that states will support and, by their actions, undermine it concurrently.

Reform or revise?

It’s quite clear, I think, that WHO is in a seemingly endless and destructive cycle of reform. This may be a desirable position for WHO to be in from the perspective of some of its members, and perhaps has been deliberately orchestrated by them. But it’s a contradictory and self-defeating position because many of the ‘reforms’ being required of WHO result in it becoming less efficient. A couple of colleagues and I discuss this in a paper that came out in the BMJ a few weeks ago, but others have pointed it out too (see Browne 2017; Schmid et al 2021). So while I understand the need for reform, reform is an over-used term. Sometimes, all that is required is revision. My own view is that the Organisation should be given time to breathe, and be allowed to make some revisions to the way it works rather than perpetually being asked to jump through hoops.

Achieving more with less

To meet its technical and mandated function – to provide advice to states in the interests of public health and health for all – reforms are required. We lay out below provocative ideas for reforming WHO’s own ideals of what it can achieve in the area of global health, and indeed call for the organisation to embrace the political status it has as a UN organisation. This is a radical step: it is not an argument for WHO to have more but possibly for WHO to do less to enable it to excel as the lead international organisation for health. States have designed ‘natural’ limitations around WHO in areas such as funding and governance; and there is little evidence that states desire to change these conditions to empower WHO. It is possible, we contend in this piece, to make the case for WHO to maintain its status of an authoritative public health figure that is finite in its capacity and political reach. As always, WHO will have to be what states want it to be (emphasis added).

Wenham and Davies, 2023 p2

This argument is one that is gaining some traction: WHO does too much and can’t do everything sufficiently well, so it is better for it to do less but do that to a high standard. The reason for this is because of the “natural limitations” that states have imposed on WHO with regard to funding and governance, and there’s no reason to think that states are going to revise these limitations anytime soon. I’m not sure to what ‘natural limitations’ Wenham and Davies refer (my bad), but there is a counter argument. The reason why WHO is not ‘excelling’ in all areas of its broad mandate is because it is not being funded sufficiently; and/or it tries to do something on meagre rations, unsurprisingly doesn’t do it very well and then is not given a second chance to do it better; and/or tries to do something, screws up but isn’t given a second chance because it’s enemies jump on that failure as an opportunity to further limit its resources.

We’ll get to the funding issue a bit later, but an obvious parallel presents itself: think of the WHO as the UK’s NHS. Over time, the Conservative government has deliberately run that institution down, split it up, chipped away at some of its ‘core’ functions because, fundamentally, the Conservative government does not want a publicly-funded and delivered health service. Similarly with the WHO: if certain governments (or wealthy individual donors – it’s no secret that Gates doesn’t like the way that WHO is run) don’t want a public-focused, democratic and representative IO leading global health, then reducing its mandate would be one way to diminish its authority (arguably WHO’s strongest suit). Wenham and Davies argue that a reduced mandate could ensure, perhaps even enhance, WHO’s authority. But that’s a major gamble and the stakes are very high. It’s not an evidence-based position and I wouldn’t take the bet because the risks are too high.

I know, but at least they’re good at convening!

In a recent BBC program, a reporter asked – apparently with a straight face – what the UK’s newly appointed King King Charles III’s “superpower” was! Surprisingly, they didn’t identify as a superpower his ability to remain popular with the masses while squirrelling away a vast fortune from owning vast tracts of our land. No, the King’s superpower was, in fact, his ability to convene. Who knew? And so it is with WHO, apparently. Convening is always rolled out as WHO’s superpower. Here’s Wenham and Davies’ take on it: “The strength of WHO is the organisation’s convening power as the lead international health authority: the WHO, unlike any other organisations in global health, can bring states to the table and can create meaningful agendas and work plans – ranging from mental health to tobacco control, UHC, SDGs to clinical trial guidance and assistance”. WHO – in essence – provides an important administrative function. Is it good at anything else? Well, the authors argue, WHO retains its “technical prestige” through its Emergency Use listings, coordination of technical advice and as the forum for agreeing international health standards. The authors are clear – well, sort of – where the gaps are: “The gaps that WHO cannot overcome through reform are in implementation, funding and securing government commitment to WHO standards. We suggest that rather than seek powers that states do not wish to give it and see it fail, WHO should audit and enhance the governance areas that achieve greatest state compliance”.

If implementation, funding and securing commitment to standards are not reformable then that means that we’re stuck with what we’ve got, right? There is no room for funding reform and no chance of WHO securing government commitment to WHO standards (even though standard setting is supposed to be one of WHO’s core strengths?) I must be missing something here because in the following paragraph the authors offer this recommendation: “A dedicated review of WHO’s structure and mandate should be accompanied by a renewed commitment to assessed contributions to the organisation”. So funding reform is possible as long as – and how many times have we heard this before – it is accompanied by “a renewed system-wide reform”? This is a standard quid pro quo narrative that underpins WHO’s principal/agent relationship – something for something. Neither side wants the other to gain too much control, but some of the principals in this relationship (some wealthy states) really don’t want the agent (WHO) to get ideas above its station. Their preferred method for keeping WHO in check – as I mentioned previously – is to constantly keep it in a state of reform.

Something is structurally defective in the heart of Denmark

I think most people are agreed that there is a structural defect at the heart of WHO’s funding model, one consequence of which is ‘pockets of poverty’ where some health issues are over-funded and some under-funded. Because the funding is conditional, WHO can’t just move it around to fill the empty pockets. But this is an argument about the model of funding, it’s not an argument about whether WHO needs more/less funding overall. As we argue in our paper linked above, we really know very little about why member states prefer to fund WHO through voluntary contributions – there is some research on this, but not that much.

The corollary to the ‘do less’ argument about WHO’s mandate is the argument that WHO doesn’t need more money. The group (and you’d be surprised-ish to read who was in that group) led by Clift in 2014 argued along these lines: “The WHO’s problem is not inadequate income…a WHO focused on its core tasks could do more good with less money” (px). This argument was also rehearsed by Richard Horton recently during a panel discussion we both attended, and also one that sounds very similar to the arguments around comprehensive and selective primary health care during the 1970-80s. ‘Doing too much is too expensive’, governments wail, ‘we must be selective’! Certain health issues lend themselves to precise targets which are much easier to measure, which in turn aligns with results-based financing, which makes it easier to demonstrate ‘value-for-money’ and thus easier to justify expenditure to governments with a horribly skewed list of priorities.

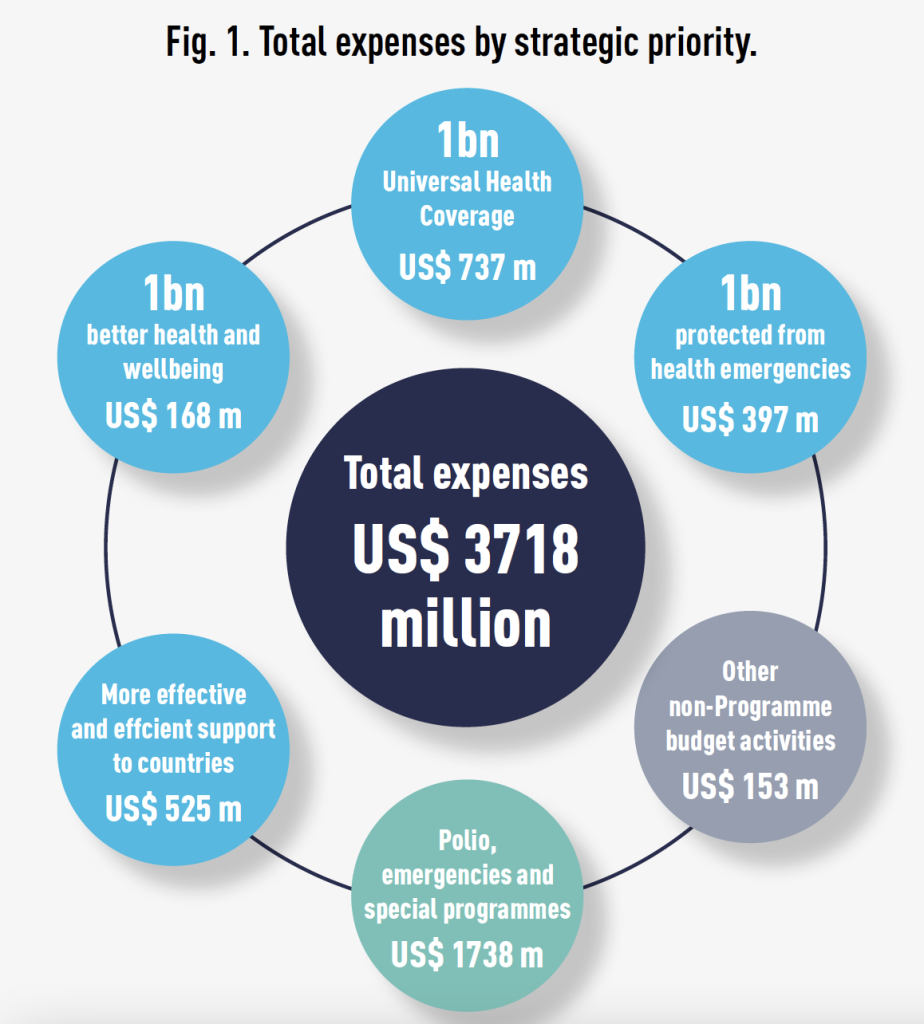

Wenham and Davies are in the ‘do less’/’no additional money for WHO’ camp. They make the following ‘provocation’: “This is the challenge that may create discomfort for WHO advocates: not more funding but more alignment between states expectations of WHO and WHO compliance, pull and expertise”. In other words, no more money for WHO and instead make sure – somehow – that there is alignment with what the funders want to fund and what WHO is good at. If there’s a gap in funding for something like universal health coverage, Wenham and Davies’ suggestion is – in effect – for states to just stop funding it through WHO and fund recipient countries directly. Similarly, I guess, for the other unfilled ‘pockets’ – health emergencies and better health and wellbeing. Hypothetically, if that happened and donors just stopped funding UHC, health emergencies and health/wellbeing, would they match the money not spent on these issues to those other health issues they do like to fund? Or would we just see a spectacular budget reduction? As Figure 1 below from WHO’s audited financial statement 2021 summarises, we’re talking a significant portion of WHO’s budget here: $1.3b.

These are very broad categories of health promotion, protection and prevention which states prefer not to fund. I would argue that it is better to try to understand why these health issues are less funded than other areas, and work to resolve any issues relating to that rather than throw in the towel and remove them from WHO’s mandate altogether. Having raised the question, the authors then seem to demonstrate that it is moot anyway because of governance challenges and no appetite from donors to ‘decouple’ health emergencies from WHO – so I’m not sure why we are even discussing this as an option?

Show me the money! No, really, where is it?

The main point to emphasise as loudly as possible, and one which just seems to get ignored in discussion of WHO funding, is that we are talking about tiny amounts of money. I mean, really tiny. I don’t think people realise just how little funding WHO receives. It’s so laughably small, that even discussing budget cuts is an insult to one’s intelligence. It’s beyond frustrating to observe working groups like the Working Group on Sustainable Financing scramble around trying to achieve modest increases in member states’ assessed contributions, or to watch WHO embark on yet another round of reforms in order to satisfy its calls for essentially minuscule sums of money. Wenham and Davies know that WHO is absurdly under-funded, and provide their own example to illustrate this fact: WHO’s budget = annually “about how much it costs to run the NHS across England for 6 days”! Just think about that for a minute: the economies of 194 countries won’t cough up more money than that!?

The final contribution on funding from Wenham and Davies is a bit confusing to me: “Addressing the funding shortfall through more voluntary funds or assessed contributions, for it is clear the WHO can’t have both, is a vital question for WHO and its members states to consider”. I agree that we need to address the shortfall, although I thought that the authors were arguing against more funding? This sentence suggest that additional funding is still on the table as an option? That aside, it is possible – indeed entirely desirable – that WHO have a healthy mix of both ACs and VCs. Nobody wants a WHO fund entirely by ACs. The problem, as we all know, is that we have gone way too far towards the VCs – 88% of WHO’s budget in fact.

Concluding thoughts

“It is important to note that the WHO, however ideal we might envision it as an institution for realising the right to health, is not a panacea, and at times of crisis these institutions will fail”. It’s extraordinary to read such a statement. To return to the key terms we started with – ‘we’ and ‘need’, ‘want’ and ‘deserve’ – surely, surely, if nothing else, in times of crisis we – and by ‘we’ I mean the global population but especially the most vulnerable – need our institutions to succeed not fail? And not just succeed, but excel. This is also what Wenham and Davies want; they want WHO to excel. Unfortunately, their solution would lead to a race to the bottom. It would start with a genuflection to those states who would do WHO down; identify what they want from WHO and structure the Organisation around those priorities; set WHO on a path of fundamental reform – so fundamental that its mandate would fall away; pair back the Organisation’s remit in order to remove entirely its political function, leaving it to perform an administrative, convening function and issue technical advice. The race would end with a denuded actor, shorn of whatever authority it currently has, watching from the wings as a smorgasbord of private-leaning IOs, IFIs, partnerships, etc, fail to do all the things WHO could have done much better if only ‘we’ were enlightened enough to fund it adequately. At the end of the day ‘we’ – and here I mean you – have to decide whether we want WHO or not because we are in danger of losing it. Do we want an organisation at the heart of global health that can hold – or at least try to hold – states to account for their health commitments? Do we want an organisation with a sufficiently broad mandate to ensure the highest possible health for all? Do we want a public health-oriented organisation that has the authority and resources to not just succeed but excel in times of crisis? ‘We’ deserve a fully-resourced WHO that can do what it was mandated to do 75 years ago. Our governments need to grow up and make that happen.

Andrew

One comment on “The WHO that “‘we’ need”?”