The 76th World Health Assembly (WHA) is being held next week, which is good news if you’re in the Geneva rental market. Watching the WHA, the Geneva Global Health Hub (G2H2) is coordinating ‘WHA Today’, a daily “lounge for civil society exchanges” and various other meetings throughout the week. The Peoples’ Health Movement and Public Services International run the WHA Watch, an intensive two-weeks of WHA monitoring, advocacy, and lobbying by a dedicated group of global health activists. Underpinning their work is the wonderful resource WHO Tracker. A huge amount of work goes into all of this work, driven by the need to provide a ‘critical’ civil society voice to the proceedings at WHO HQ.

I was invited to a session this week as a ‘resource’ for the ‘watchers’ as they prepare policy briefs for the various items on WHA’s agenda (you can access all of the WHA documents on WHO’s governance webpage). My contribution to discussion was a garbled mess that managed to tick off all the classic ‘don’ts of your standard online presentation. Apologies, comrades! The remainder of this post is what I meant to say.

The replenishment mechanism

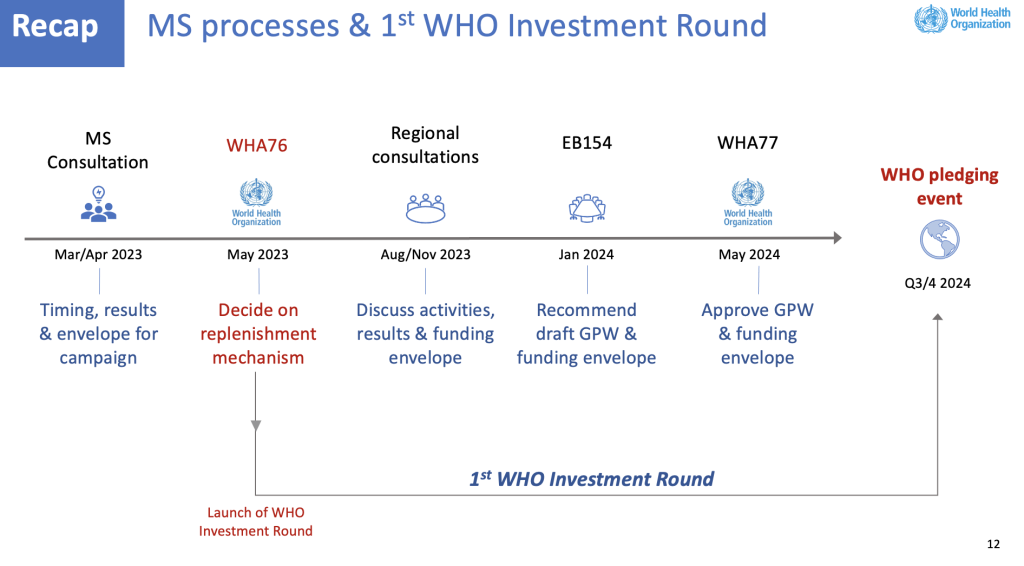

I’ve written about the conception of the idea of a replenishment mechanism for WHO previously. It has its origins as a recommendation in the Main Report of the Independent Panel on Pandemic Preparedness and Response (IPPPR). That recommendation was picked up and adopted by WHO’s Working Group on Sustainable Financing (WGSF). Member states approved the recommendation at last year’s WHA and it was taken forward to WHO’s Executive Board in January this year. Since January, there have been two member-state consultations (in March and April), with the feedback from those sessions feeding into a feasibility and options paper which will be discussed next week at the WHA.

It’s an understatement to say that A76/32 ‘Sustainable financing: feasibility of a replenishment mechanism, including options for consideration’ reflects a significant shift in thinking about the way that WHO should and will be funded in the future. WHO has also produced a PPT presentation for non-state actors, slides from which I’ll include below. Perhaps the best way to structure a critique of the document is through three key concepts that underpin the WGSF’s understanding of sustainability: flexibility, predictability, and priority setting. I think this is a more useful approach than to structure the critique around the WGSF’s six ‘principles’ because a) the document A76/32 does that for you, and b) focusing on sustainability helps you to answer the question ‘Is it worth it’?

Flexibility

Flexibility is the WGSF’s answer to the ‘structural defect’ underpinning the current WHO funding model. Everyone knows that the vast majority of WHO funding is voluntary. Recent analysis has shown that 88% of program funding is in the form of voluntary contributions, with the remaining 12% provided by member states through fully flexible assessed contributions (ACs). The WGSF recommended in its report that assessed contributions increase over time, with the “aspiration” that 50% of the base segment of the program budget (using the 2022/23 budget as a fixed baseline) be provided in this way (NB: that the IPPPR recommended 66%). Given that, currently, only 20% of the base segment of the program budget comes from ACs, this recommendation represents a significant advance in the pursuit of flexibly funding WHO.

What about that portion of the base segment not covered through ACs? Well, that’s where the replenishment mechanism, or ‘WHO Financing Mechanism’ to give it its preferred name, comes in. The Financing Mechanism (FM) will fund whatever amount is not covered by the staggered AC increases, meaning it would need to find more money early on but less over time until by 2028/29 it only needs to fund 50% of the base segment. How flexible will the voluntary contributions (VCs) secured through the FM be? The WGSF requested “fully unearmarked” VCs but document A76/32 only mentions that the FM has a goal of full financing of the base segment “with more flexibility” (para. 11). This is how this more limited ambition is described:

“the short timeframe for implementing the first WHO investment round requires that the primary goal should be the full financing of the base segment of the expected financing envelope for the draft Fourteenth General Programme of Work, with increased flexibility of that financing, rather than full flexibility at this time”.

Para 21

Furthermore, non-state actors (and remember that this will include significant donors to WHO such as the Gates Foundation) are not committing to provide fully flexible VCs (para. 22). Whether they commit to semi-flexible ‘themed’ VCs remains to be seen. Just in terms of flexibility, then, it is not clear that the FM offers any significant advance to what WHO currently receives: currently, there is some commitment by a few donors to increasing the flexibility through semi-flexible VCs. The main change in flexible funding in the future will come from MS commitment to increasing their ACs, but this is a completely separate agreement to the FM.

Predictability

Knowing how much money you’re going to receive is one thing; knowing when you’re going to get it is quite another. WHO’s ACs are known in advance and are given to WHO at the start of the biennium, so it loves those! But, as we’ve noted, only 12% of its program funding comes as ACs. So how can we make the VCs WHO receives more predictable? Answer – a replenish…sorry financing mechanism. WHO’s FM will replace the current unpredictable drip drip of VCs with “multi-year commitments”, the idea being that 4 years of funding (2025-2028) will be pledged by donors. This will be known as an ‘investment round’.

The new commitment from state and non-state funders will be facilitated by a couple of new tricks: first, a new forum will be set up, the investors forum, comprised of all funders, and where the WHO’s draft 14th General Program of Work will be discussed. The hope is that these discussions will ensure that the GPW is something the donors understand and can get behind, and so ensure a successful first ever WHO ‘pledging event’ in the latter half of 2024. The investors forum will meet each year to review progress of implementation of the 14th GPW.

It’s not clear how big a problem predictability is for WHO relative to, say, flexibility of funding. The most predictable funding is also the most flexible (member states’ ACs) because it appears in WHO’s bank account right at the start of the biennium. If funding pledged comes shortly after the pledging round, then I guess we are in a position where we can say that, yes, WHO has predictable – essentially up front – funding for the 4 years of the investment round. That would be a qualitative difference and an advance for sustainable funding. But if the pledge is more of a promise for the funding to appear at a certain point over the next 4 years, is that much better than the uncertain (but expected) arrival of VCs at some point during the current biennial model of funding? You can see how much VCs WHO receives midway through its biennial cycle in its annual Audited Financial Statement. For example, in 2022 WHO received $3656m in VCs.

Priority setting

Predictability and priority setting are two-sides of the same sustainability coin. With VCs, it’s not just about when the money arrives but about what strings are attached to it. It’s unpredictable in the sense that WHO doesn’t know what the donors stipulate the money must be spent on. As is well known, this has led to ‘pockets of poverty’ in financing the triple pillars of health that underpin WHO’s current GPW. So, if the pledges are forthcoming in a timely manner and there is more flexibility in what the money can be spent on, then we’re heading in the right direction in terms of sustainable funding. Except that as was noted above, there doesn’t seem to be much interest, yet, for donors to be more flexible in their VCs.

But priority setting has an importance distinct from (even if related to) sustainability: power. The WGSF report highlighted the desire from non-state donors to have a say in what WHO prioritises in its GPW. It’s not fair, non-state donors say, for us to cough up the dosh but not get to say what it should be spent on. Except that it’s totally fair, of course. But we should park that debate for a minute.

Member states already have a say in the health priorities of the WHO budget because WHO is, after all, a member-state-led organisation. But NSA’s don’t. The Gates Foundation currently contributes a lot to WHO, the most by far of any NSA, but most of its money goes to specific health issues (67% of the $900m it has given to WHO for the 2022-23 biennium goes to Polio, for example). If the Foundation is going to continue to spend similar amounts of money to WHO once the polio transition has been completed, won’t it want to have a say in what it spends its money on? Of course, it will. And if it doesn’t, then maybe it will decide to fund other initiatives, partnerships, whatever? So you could interpret WHO’s Funding Mechanism and Investors’ Forum as architecture designed to satisfy key NSA donors’ wishes but under the guise of a sustainable funding agenda. It is about ensuring sustainable funding, but it’s also about power: the power for NSAs to have a more explicit role in shaping the funding priorities of WHO’s budget and – more fundamentally – its priorities.

Is it worth it?

The reforms about to be approved will commit WHO to a LOT of work. This is what WHO is going to have to do in just twelve months:

- Scrap its current GPW and redesign a new one, from scratch;

- Further conceptualise and design all of the architecture associated with the new Funding Mechanism: investment rounds, pledging events, investors’ forum.

- Implement said architecture.

But for what? Luke warm commitment from MS to increased flexibility in the medium-term (post 2028) but not in the short term (2024-2028), and cold commitment from NSAs; the potential for upfront funding for four years, although that’s not clear; and the prospect of its budget priorities further diluted and politicised through an investors forum? And this doesn’t even include the risks briefly described in the report: political, economic, and reputational risks to the Organisation.

It seems like a lot of effort for little return. The big advance in the sustainability debate is the aspirational commitment from MS to increase their ACs to 50% of the baseline 2022-23 base segment of the program budget by 2028. That at least is something clear that we can hold our political leaders to account for. But this WHO Financing Mechanism? I guess time will tell. At least if it fails to meet expectations, we’ll know who to blame. Won’t we Helen, Ellen, Mark, Michel et al?

Andrew

Priti Patnaik reported on 23rd May some significant revisions to the wording of para 2 of A76/32, p6, including a new para 2b which seems to row back and contradict previous MS commitments to ‘unearmarked’ VCs: https://genevahealthfiles.substack.com/p/the-us-allegedly-threatened-to-withhold

Here is the revised A76/32 text:

(2) to urge Member States[2]and other donors[3] to ensure the full financing of the base budget segment of the Fourteenth General Programme of Work, and to continue to strive to provide WHO with unearmarked voluntary contributions consistent with the recommendations of the Working Group on Sustainable Financing adopted by the Seventy-fifth World Health Assembly;

(2bis) to continue for WHO to accept, alongside unearmarked voluntary contributions, voluntary contributions[4] that are earmarked and/or single-year contributions from Member States and other donors and further increase transparency of reporting on voluntary earmarked contributions and on their impact and allocation across the three levels of the Organization