According to WHO’s dedicated Investment Round (IR) webpage, the IR (which was launched in May this year) “aims to mobilise predictable and flexible resources from a broader base of donors for WHO’s core work for the period 2025–2028”. It has until the end of this year to secure pledges of approximately $7.1bn from state and non-state donors. Unfortunately, as I describe in this post, it’s having to do so at a time when its donors’ voluntary contributions (VCs) are falling significantly. I’ve evoked the metaphor of a sinking ship. To be clear, WHO is not an actual ship it’s an International Organisation, but for the purposes of artistic licence think of it as a ship that’s taking on water with its Secretariat desperately bailing. Currently, its efforts are keeping the ship afloat. But for how long?

2025-2028 is the four year period covered by WHO’s 14th General Program of Work (GPW), the latest draft of which was presented to the World Health Assembly in May. The GPW is a high level strategy document that includes an indicative financial envelope for the four year period it usually covers. For GPW 14, that envelope is $11.13bn. Note that this is just an indication of the amount of money required and is provided as a guide to donors. The detailed financing requirements for what WHO does continue to be provided in its biennial budgets (the relevant ones for the period of GPW 14 are and will be 2024-25, 2026-27 and 2028-29). The $11.13bn will support only the ‘base’ segment of WHO’s programs and will come from two funding streams: $4bn will come from Member States assessed contributions while the remainder ($7.1bn) will come from the voluntary contributions of state and non-state donors. As stated in the draft GPW 14, the objective of the IR is to raise the majority of these voluntary contributions before 2025, and “with a decisive shift towards flexible funding”.

The IR is a new name for an old idea. It was first mooted by the current DG of WHO Dr Tedros’ predecessor Margaret Chan back in – checks notes – 2011 (see quote below). It was then picked up again (and recommended) by the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response (IPPPR). The Working Group on Sustainable Financing adopted the IPPPR recommendation and in turn recommended to the WHO Secretariat that it encourage Member States to support it (which they agreed to do). And so, here we are. The IR was launched and the pledges are rolling in – just a bit slowly. As you can see from the IR webpage, pledges currently total about $1bn (thanks to a boost via the World Health Summit in Berlin last week). So, $6bn more to go by Christmas. It’s anticipated that much of the heavy lifting in terms of pledges will happen at the G20 Leaders’ Summit in Brazil next month, the last event on the pledging calendar for 2024 (so get your wallets ready, world leaders).

WHO will therefore seek to attract new donors and explore new sources of funding. In exploring new sources of funding, the aim will be to widen WHO’s resource base, for example, by drawing on Member States with emerging economies, foundations and the private and commercial sector, without compromising independence or adding to organizational fragmentation. WHO will also examine the advantages of a replenishment model for attracting more predictable voluntary contributions.

Margaret Chan addressing the 64th WHA in May 2011 A64/14 p13

It’s interesting to see who has got in quick with the pledges. Take a look on the IR’s ‘Commitments’ webpage. First off the blocks was Qatar with $4m followed quickly by the EU with $275m and Singapore with $18m. Voluntary contributions have, historically, come from the European Commission (EC) which is the executive arm of the EU. So, I’m going to assume that the EU and EC are being used interchangeably here. In the VC documentation, the EC is a major donor of VCs to WHO, typically donating approx $200m every year. Singapore has significantly exceeded its historical donations, pledging six times more to the IR than its entire voluntary contributions over the past decade. Similarly with Qatar, pledging twice as much to the IR than it has donated to WHO since 2011.

It’s noteworthy that one third (14/47) of the pledges so far come from African Member States. Slightly weird is the precise amount of $10m pledged by no less than 7/47 pledgers – like there’s some unspoken game going on around how much a donor should pay. Maybe the heads of the African, European and Islamic investment banks all met up at a coffee shop in Geneva back in May and agreed that $10m was how much they were each going to pay? Anyway, I’m sure WHO’s Secretariat will be pleased to see some new kids on the block as they are exactly who/what the IR is hoping to attract. So, welcome ATscale ($8m), Hamdard Foundation ($0.05m), the Institute of Philanthropy (aka the Hong Kong Jockey Club – $11.2m “cumulative”), Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development ($5m), Roche Africa ($1.6m), and Tamasek Foundation ($10m),

One thing that isn’t clear from the pledges is whether the amount is all that WHO can expect from each donor for the four year period of the GPW. For example, Germany has pledged $263m and Norway $94m, while the Gates Foundation has confirmed a “regional” pledge of $42m. We won’t know until next Summer exactly how much each of these donors contributed to WHO in 2024, but for the biennium 2022-2023 Germany’s VCs were a (relatively) whopping $826m, Norway $112m and Gates contributed $746m. Presumably, there is more to come from Gates as, year-on-year, it has contributed approx $200-400m to WHO. But it’s less clear how other donors will fund WHO in the future. I’m asking because one of the main reasons for having the IR is to increase the predictability of funding. It’s not going to achieve that goal if VCs just drip-drip into the IR over a prolonged period of time. For the IR to work, we need to have pledges upfront. Otherwise, what’s the point of it?

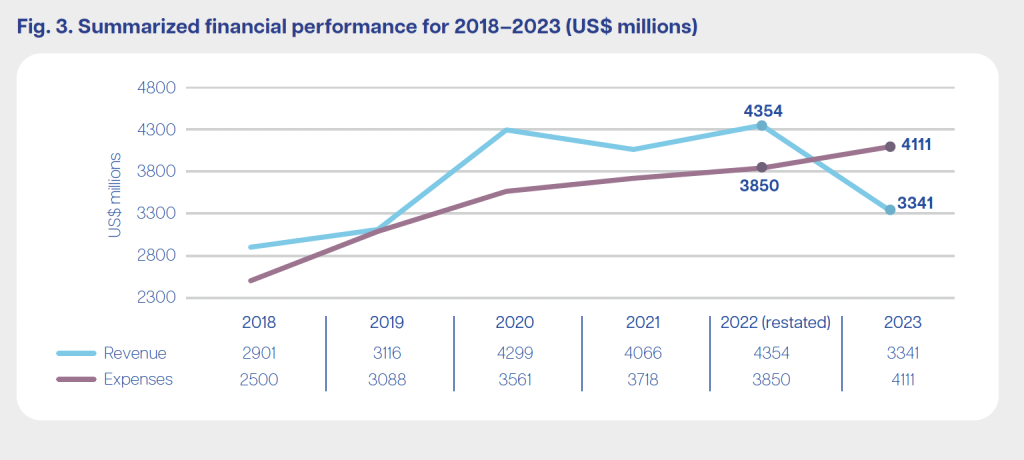

One major problem, as you will know if you have read WHO’s Audited Financial Statement 2023 (please tell me that, besides its author, I am not literally the only other person on the planet that has read this document – I am, aren’t I), is that donors are significantly reducing their VCs to WHO now that the pandemic has receded. Take a look at the figure below taken from the Statement. Revenue to WHO has fallen quite dramatically since 2022 mostly in terms of VCs from its major donors. For example, VCs from the US fell from $739m in 2022 to $368m in 2023 while Germany’s VCs fell from $597m in 2022 to $229 in 2023. Overall, between 2022 and 2023 VCs have fallen by $911m. Unfortunately, it’s not just a reduction in VCs that are causing headaches for the WHO Secretariat as collections for 2023 of Member States’ ACs were 73% of the total invoiced (down from 81% in 2022). At the same time that revenue is falling, WHO’s expenses are increasing and in 2023 were the highest ever at $4111m. Despite the financing gap, WHO was able to fund its activities thanks to unspent revenue from previous years. But that ‘buffer’ money has gone now.

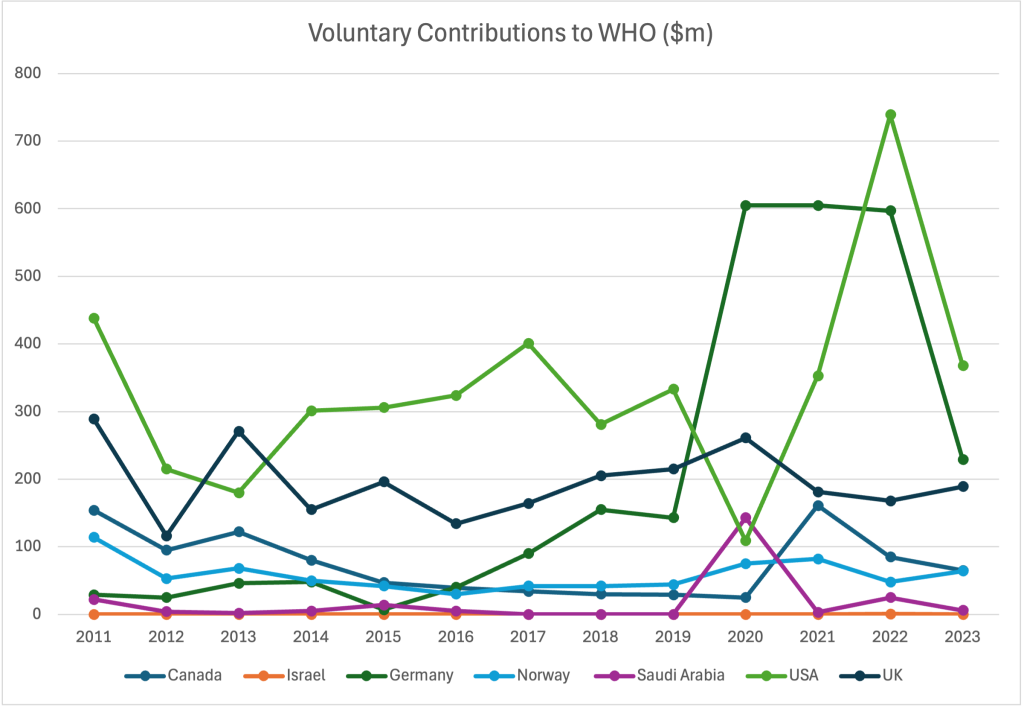

The Secretariat is framing the funding gap as a ‘we-told-you-so’ example of the vulnerability of WHO’s reliance on a small number of big donors. It points out that 82% of the reduction in revenue comes from amongst its top ten donors. While this is true, most – but not all – Member States have reduced their VCs to WHO. For illustrative purposes, I’ve compiled VCs from a selection of donors in the figure below. Norway and the UK are examples of MS’ that have increased their VCs (Norway from $48m in 2022 to $64m in 2023; the UK from $168m to $189m). But you can see how precipitous the fall is for donors such as Canada, Germany and the US. I’ve added two other MS to the graph: Saudi Arabia and Israel. Given their wealth, both donors have been extraordinarily stingy in their contributions to WHO. Saudi Arabia typically gives either no VCs or VCs in the single digit millions. 2020 was the exception when it gave WHO $143m (!) Israel (a country that never struggles to spend billions on arms which it then uses to destroy other states’ health infrastructure) voluntarily contributes to WHO each year anywhere between a flat zero to $50k – (yes, that’s a k not an m). In case you’re interested, Palestine doesn’t typically contribute to WHO with the exception of 2020 when it contributed $276k (more than Israel has contributed to WHO in the last 15 years). The point I’m making is that you often hear apologists for such stinginess (I’m giving Palestine a pass here for obvious reasons) claiming that Member States are in financial dire straits and can’t afford to pay more. For the millionth time, this is 100% bullshit.

Ok, so where does that leave the IR? Well, it’s here after nearly 15 years in gestation! Unfortunately, its birth coincides with deep uncertainty around the political future of its number one donor – the United States – and also a potential financial crisis. It’s not at all clear to me how WHO will manage the evident drop in revenue and continue to do what it wants to do at its current scale. This is why I evoked the metaphor of a sinking ship. WHO’s Secretariat know that WHO’s finances are in a precarious position (not dire but not buoyant either). There are a lot of moving parts and I wouldn’t be surprised if there is a Special Session of the Executive Board in December to discuss this, as well as the IR. But let’s see. We will have a better understanding of the IR after the G20 in November. At the very least, Member States need to reaffirm their commitment to financing WHO’s GPW 14. I’m not expecting the IR to reach its $7bn target by the end of the year but, again, let’s see. For now, the Secretariat just has to keep bailing.

Andrew

It’s November 22nd, 3 days after WHO announced at the G20 that it had secured $3.8bn of the $7.1bn target of flexible, voluntary funding for its 14th GPW via its first ever Investment Round. I can already see the detailed percentages in this announcement of increases/improvements of this or that amount for this or that aspect of the strategy by this or that time compared with x years ago. WHO always spins their results in this way – I don’t know who writes this stuff, but they are impressively imaginative! I don’t have the energy to dive into the details but, fortunately, I don’t have to because other, and better, commentators have started to do that already.

For starters, Garcia and Benn reiterate the upbeat message of the WHO announcement and Priti Patnaik has a Geneva Health File post on it. I like this quote in her post from ‘a developed country diplomat’: “Why is there limited engagement from the biggest emerging economies? They just talk about multilateralism without wanting to pay for it”. Well, quite.

Part of the reason why I struggle often to find the energy to report on WHO funding is because the sums of money involved are so tiny and I find it genuinely pathetic that donors won’t contribute more. For example, the UK is one of WHO’s most generous donors and has pledged £392m to WHO through the Investment Round for the period 2025-28 (£98m pa). It also provides £10.5m pa in ‘membership fees’. So, in total, the UK donates approximately £108m pa to WHO. But you may be surprised to learn what other worthy causes the UK supports. Today, for example, we learn that it pays £500m pa for the privilege of having a monarchy!

Often you will hear governments whinge and whine about cash-strapped they are; how they couldn’t possibly pay more to WHO because ‘they can’t afford it’. As I’ve said many, many times before, this is bullshit. As the diplomat says, they want multilateralism but don’t want to pay for it.