No, not the daytime quiz game beloved of students and the over 70s, I’m talking about the other Countdown – the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change which has just published its latest report. As with most reports on climate change, it’s long and takes time to digest, but I am privileged to be able to spend my weekend writing about it. In case you don’t know what the Lancet Countdown is or does, here you go. You can also read Ch7 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Working Group 2 report Health, Wellbeing and the Changing Structure of Communities and ask yourself why. As in, why do we have both?

Ok, so, where to start? How about with the newly-formed Lancet Countdown/World Health Organisation “strategic partnership”. I didn’t see that coming, did you? Funded for at least the next five years by Wellcome, we learn in the report that the Lancet Countdown is going to partner with WHO “to bridge the data gap by improving the availability of national-level data and delivering guidance, blueprints, and tools to support countries in standardised data collection and reporting” with the priority for that partnership being “to deliver rigorous and actionable scientific data and to move from tracking the soaring health threats of climate change to informing policies that enable a healthy future for all” (p8). Interesting, no?

By way of context, it is important to underline the fact that even though WHO prioritises climate change as a number one priority in its 14th General program of Work, for all intents and purposes the Organisation has zero money in its budget to fund its work (less than 5% of its budget supports WHO’s work on Environment and Health broadly defined, of which a tiny fraction funds WHO’s work on climate change). So, I can understand why the Organisation sees merit in partnering with a bunch of climate change researchers.

Still, it raises some red flags, doesn’t it – the most obvious one being that WHO has no money to spend on climate change and has to resort to other means to ensure that this work gets done! Another red flag is Wellcome. Wellcome funds a lot of climate change research. Why? Influence. This is Wellcome’s number one priority and it is now able to influence climate research within WHO via an enabler – The Lancet Countdown. Wellcome and WHO have very close ties, of course – Jeremy Farrar was the Director of Wellcome until February 2023 when he took up a new position as WHO’s Chief Scientist, and Wellcome has recently committed $50m to WHO’s Investment Round. People often cite the Gates Foundation as having undue influence over WHO’s priority setting (which it does) but I’d also be casting my gaze across Wellcome’s bow, if I were me.

Finally, the Lancet Countdown itself. Maybe not as red a flag as the previous two but still worthy of some critical hand-wringing. First, I am uncomfortable with an academic journal (owned by an aggressive publishing company – Elsevier – owned by an equally aggressive parent multi-national company RELX) driving climate and health research. At the end of the day, these are profit-making entities not generators of public goods. Second, publishing in the Lancet is good for CVs and, like moths to the flame, good academics can easily become enthralled by its glow. Result – a leaning towards group think. Hard to demonstrate, harder to prove, but – and this is especially true of a topic such as climate change – if putting your head above the parapet means you losing your position within the network, then would you do that?

I’m not necessarily referring to the research when I mention group think, but more of that below. No, I’m thinking here about strategy. Consider, for example, the thorny question of advocacy. You may be surprised to learn, for example, that the Lancet Countdown “is grounded on scientific rigour, non-partisanism, and non-advocacy”. Scientific rigour – check; non-partisan – check; non-advocacy – che…hang on a second, what!? The Lancet Countdown is non-advocacy? Which idiots said that? Oh, the Lancet Countdown leads Marina Romanello and Anthony Costello.

To be clear, there is no mention of advocacy in the report. The executive summary emphasises the report’s monitoring role and, later, the aim “to move from tracking… to informing policies” (p8). Nevertheless, the claim that the Lancet Countdown is “non-advocacy” is patently false as there are many, many examples within the latest report that are most definitely advocating a particular policy and/or approach to socio-economic development that governments should adopt – a ‘just transition’ for example. Tell me if this isn’t advocacy: “Importantly, a global transformation of financial systems is required, shifting resources away from the fossil fuel based economy towards a zero emissions future” (p3). Or what about the report’s support for Indigenous knowledge: “Furthermore, respecting, recognising, and promoting the use and transmission of Indigenous knowledge is not only crucial to safeguard Indigenous peoples’ health in the face of climate change but can also inform further adaptation policies that benefit society as a whole”. There are lots of examples of advocacy in the report, I’ve just picked out two. But, I mean, you only have to read its sub-title – “facing record-breaking threats from delayed action” – with its sub-text ‘hey, you, Governments, speed the fuck up!’ to get my point. This. Is. Advocacy.

It’s not just that the Lancet Countdown does advocate; no, it’s also that it should advocate, shouldn’t it? Don’t we need a report that provides a compelling narrative about what governments should be doing that is grounded in the best and most compelling evidence? I thought that that was the Lancet Countdown’s USP? We already have a technical group doing work on marshalling the evidence together on climate change and health in WG2 of the IPCC (see link above). Do we really need another one? The Lancet Countdown is annual, so there’s that going for it I suppose. Still, I’m left scratching my head by the incongruity between Romanello and Costello saying that the Lancet Countdown doesn’t and shouldn’t advocate and then reading the report itself. I don’t know why they would come out swinging from the non-advocacy corner now, but I imagine it is linked to the newly-created strategic partnership and also its new funder.

In their letter, Romanello and Costello (neither of whom, by the way, were experts in climate change prior to their appointments at the Lancet Countdown – Romanello was/is a trained biochemist and Costello was/is an authority on maternal and child health) appear anxious to underline the science, rigour and reliability of the evidence the report provides to “inform policies”. Fine. But, are they really now drawing a line at wanting to change policies? If so, then that’s a real shame. I also wonder if this explicit clarification that the Lancet Countdown is non-advocacy is a sign of things to come? Should we expect a much more technical feel to the report over the next five years, for example? And, to return to the group think point mentioned above, should we expect internal disagreements about the advocacy function of the report to be settled by the pro-camp being shown the door? If so, expect much more conservative reports over time.

Actually, you can see this happening already. Gone are the frantic hand-waving exclamations that we should all ‘shout from the rooftops’ about the impending catastrophe of climate change (Costello’s words, not mine). Instead, take a look at the evolution of the report’s sub-titles over the last few years: 2021 – “code red for a healthy future”; 2022 – “health at the mercy of fossil fuels”; 2023 – “the imperative for a health-centred response in a world facing irreversible harms”; 2024 – “facing record-breaking threats from delayed action”. What might we expect in the coming years – 2026 – “indicator 3.2.2 showing a modest improvement but indicator 1.7 is 13% down on last year”?

One final reflection comes directly out of the correspondence myself and colleagues had with Romanello and Costello. In our letter to The Lancet, we offer a mild critique of the Lancet Countdown for being, in our view, too optimistic in its reporting of climate change. We note the relative absence of comment on tipping points in the reports (and little/no mention of their potential as an existential threat to civilisation). Just two Lancet Countdown reports refer to tipping points directly (the 2024 report doesn’t) and none cite any of the health literature supporting tipping points (see this paper for example). Here’s how the 2024 report describes what might be in store for us: “The impacts seen to date could, therefore, be only the beginning of an increasingly dangerous future, with devastating impacts on the natural systems on which humanity depend”. Scary enough, right? Maybe. I guess it depends on whether you would describe Nordic countries being completely wiped off the map by AMOC collapse as “an increasingly dangerous future” to anyone living in Scandinavia. Were that to happen, it would be an end point, with entire populations of multiple countries forced to migrate or face starvation. Describing that as a “dangerous future” in no way captures the calamity.

Previously, Costello and Romanello (and others from the Countdown team) have written with alarming clarity about the dangers of climate change for health. Their Comment “Climate change threatens our health and survival within decades” published in The Lancet in 2023 (not cited in the Countdown report, btw) ends with a quote from the IPCC: “half measures are no longer an option…and any further delay risks our missing a brief and rapidly closing window to secure a liveable future”. A dangerous future? A liveable future? Whatever that means, it needs to be spelled out to us – and pronto! Not doing so strikes me as irresponsible. Climate scientists such as Stefan Rahmstorf know all about the reticence by some in the climate science community to talk openly about worse-case scenarios. Here he is in a recent interview with Jonathan Watts of The Guardian: “Some colleagues say we shouldn’t talk about extreme possibilities like an AMOC collapse because it sounds alarmist and might distract people from more certain impacts of global heating, which are bad enough”. I’m unsure whether Costello and Romanello fall into this camp or not as they seem to want their cake and eat it – to appear scientifically respectable in their grown-up reports but also ‘go crazy’ in the comments section.

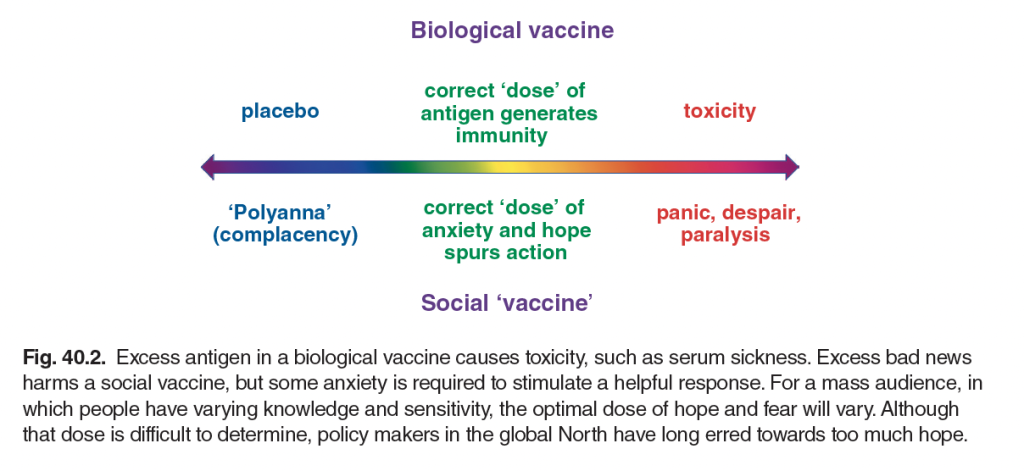

We also note that there is an uncritical presentation of Net-Zero policy in the Countdown reports, even though this policy has been widely criticised in the climate science literature. Here’s one example from the 33 mentions of net zero in the 2024 report: “A swift and just transition to a net zero greenhouse gas economy is, therefore, crucial to limit economic and health-related losses and damages but requires profound structural and economic changes and substantial capital investment”. The reader is directed towards the challenges of achieving net zero without being encouraged to reflect critically on the policy itself. We wondered out loud in our letter whether this uncritical stance had, inadvertently, contributed to the delays described in the reports. Visually, and by way of a constructive way forward, we introduced the concept of a ‘social vaccine‘ (also see the figure below) that adjusts the dose of messaging so that it is neither too doom-and-gloom nor overly-optimistic.

We were expecting a ‘thanks but no thanks’ response from the Lancet Countdown lead authors; instead, we got a tragi-comic ‘how very dare you‘ reaction where, bizarrely, we were accused of wanting to manipulate people’s mental health and emotional wellbeing, of “challenging the integrity of the scientific community” and of diverting attention away from (and absolving the responsibility of) “those truly responsible” for the delays we described. This was quite mild criticism compared to the correspondence we received in private (as often goes on behind the closed doors of academia – you’d be surprised where egos dare via email). It may be that this undeserved hostility towards criticism is a product of the tense and pressured backroom politics of the Lancet Countdown: it’s a big project and had, until recently, an uncertain future regarding its funding. Or, when you read our letter, you might also conclude that Romanelo and Costello were right, that we were indeed having a go at climate science and that we wished nothing more than to fuck with peoples heads. You decide, but recall that Romanello and Costello are the same two people who have no problem arguing that climate change threatens our health and survival within decades.

Where does that leave us? A regrettable and undesirable research partnership between WHO, an analytics corporation and an influence-seeking financing entity; a climate change and health report that advocates for a better world while wanting to distance itself from advocacy; and a couple of over-sensitive report leads who warn us with one breath about the end-of-the-world within decades but cry foul with another breath when anyone suggests that maybe this kind of warning needs to appear a bit more in their flagship Countdown report. We (by which I mean the climate change and health community) need space for open and frank dialogue with the Lancet Countdown reports team. Without it, when they ask ‘does my bum look too big in this’ – as I hope they do – who is going to tell them if it is?

Andrew

Thank you Andrew.

The latest (2024) Lancet Countdown (LCD) Report on climate change has been released. It cites 367 articles, making a total of 2107 references in the 8 LCD reports to date. None of these 2107 papers are to work for which I have been first author. Indeed, only one is to work that I have contributed to at all. (Smith et al., the health chapter in the 2014 IPCC report, was cited in the 2017 LCD).

In my opinion, given the number of my peer reviewed publications on climate and health (which date to 1991) an obvious selection bias is revealed in all 8 LCD reports. I also think it should be possible to show statistically that these 2107 refs. are biased to the work of the authors who contributed to the LCDs.

I find this bias very troubling, as the LCD reports – arguably – are regarded as the most prestigious and influential annual publication on climate change and health in the literature. I also do not think any method has been reported in any LCD report that explains how its authors screen the literature, how its authors are selected, and how the final reports are reviewed. I certainly have never been invited to review any of them.

As you note, our recently published letter (to which you contributed) in Lancet argued that the first 7 LCD reports were biased to optimism (doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01491-0). (BTW this letter is cited in my “grand challenges in planetary health” paper now in press (doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1373787)) .

As I started by saying, the most recent LCD report is similarly biased to optimism. This 8th LCD led to additional private correspondence with some of the LCD authors, with – I think – an outcome more positive than would be gleaned solely by reading the published response to our letter by Romanello and Costello. Time will reveal whether this will translate to a more representative (i.e. more scientific) cited literature in future LCDs. I won’t be holding my breath.

I also believe that there is considerable literature bias in Lancet Planetary Health. I hope that journal’s editorial staff consider the arguments in my paper now in press in Frontiers, especially the last 3 of the “grand challenges” that I describe.

These three are:

4. Foster nuanced, mutually respectful discussions about population and consumption

5. Clearer discussion of links between conflict, displacement, and planetary health

6. Stronger regulation of synthetic biology and bioweapon capacity

WRT to the sixth “grand” challenge: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-14113769/Covid-obviously-Chinese-lab-leak-covered-Beijing-British-expert-says.html is relevant. In this is stated: “Professor Tim Spector, who co-created the Zoe symptom tracker app and was given an OBE for his work during the pandemic response, questioned whether the virus could have been manipulated by scientists before it was allegedly leaked.” (For the record I published an editorial in 2020 suggesting COVID could have been from a lab – see 10.12924/johs2020.16010053).

The corruption and dishonesty in much of the global health academic community is mind-boggling, including by WHO’s recent appointment of a chief scientist who definitely contributed to suppression of a scientific discussion of the cause of the pandemic. (See our greatly delayed 1200 word letter in response to one that was fast tracked in Lancet, whose deeply conflicted co-authors (many of them, not all) include someone who became the new chied sci. for WHO: doi 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02019-5.)

Finally, the first “grand challenge” is to “reduce self-censorship, challenge power”. I hope the LCD authors do this, even if they never cite my papers.

I refer to the AMOC in my post. Please watch this 15m presentation by Stefan Rahmstorf, Professor of Physics of the Oceans, given at the Arctic Circle Assembly in Reykjavik on 19 October 2024. He provides a succinct and clear summary of what we know now about it, including its tipping point which, according to some models, may be crossed in the first half of this century.