The fallout of the second Trump/Republican administration is now being felt, not just in global health but also public health and health-adjacent meta-challenges such as climate change. Trump appears determined to dismantle the international order and re-build it to suit his own interests and the interests of those nazi-saluting billionaires now in his orbit. It’s a very dangerous mix of wealth and political power that we underestimate at our peril. I don’t believe that Trump is especially susceptible to reason, so arguments about why it is beneficial for the United States (US) to remain a member of WHO are unlikely to dissuade him from withdrawing. It is still extremely important to articulate clearly, publicly, and at every opportunity, why the WHO is vital for international health cooperation, though, because there are 193 other member states of the WHO that may be getting jittery. Trump’s actions cannot be allowed to cause a domino effect.

Trump’s withdrawal is an obvious, if crude, strategy to secure leverage over the Organisation but the WHO’s Secretariat should resist any flexing from the US in the coming months. I hope that the WHO’s DG will politely but firmly remind Trump that the WHO is there for ALL its member states not just the US. There have been many good commentaries over the last couple of days (see Priti Patnaik’s recent Newsletter, Gordon Brown’s Opinion piece in The Guardian, and Ashleigh Furlong‘s writing for Bloomberg, for example) so I really don’t have too much to add. But the world is short of white, male opinion, so here’s my ten minutes worth of cod analysis.

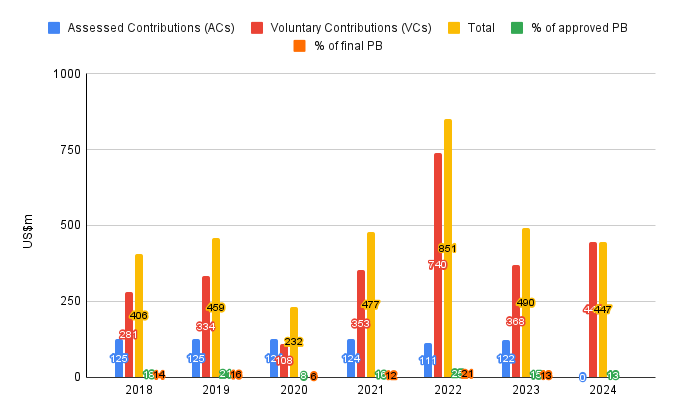

In case you missed it, here’s the video of Trump receiving for signature the Executive Order to withdraw from the WHO. “Oooo, that’s a big one”, he exclaims like a delighted child receiving a present. He then does that thing he does with his eyes – shiftily looking from left to right – pauses deliberately like some portly theatre ham, and shares with the world his little secret: “they [WHO] offered me to come back for $39m – in theory it should have been less than that”. No they didn’t, and no it shouldn’t! We then get some random numbers plucked out of the air to justify him having a go at China. Apparently, at the time of his first withdrawal in 2020, he had paid $500m to the WHO while China had paid just $39m. In fact, for the 2020/21 biennium the US paid a total of $680m and China paid $178m. Trump wouldn’t have had those numbers in May 2020, so we can only speculate where he got his from.

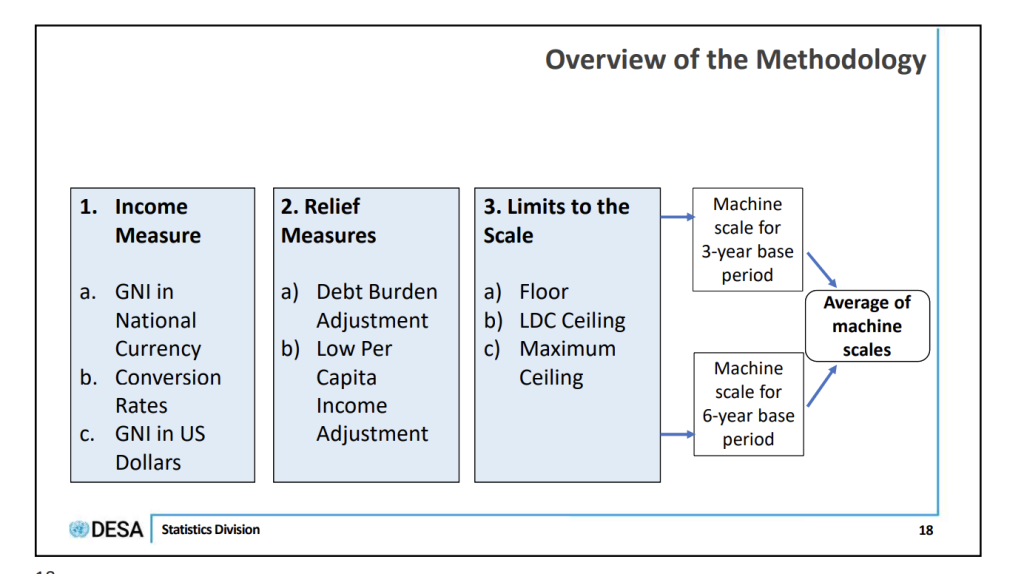

But his main beef seems to be that China has a much larger population than the US so should pay more to WHO. For the purposes of determining how much each Member State pays the WHO each year in ‘membership fees’ – aka Assessed Contributions (ACs) – population size is relevant only in relation to calculating a country’s per capita Gross National Income (GNI). Clift and Rottingen’s 2018 analysis is good on this. So, while it matters that China’s population is 1.4bn and the US’ is 350m or 325m (or whatever the fuck number Trump thinks it is – the US Census Bureau has it at 335m), it’s not for the reasons that Trump thinks it matters. Just because your country has more people doesn’t mean you have to pay more membership fees. The WHO uses the United Nations’ scale to determine how much each of its member states pay it each year. The methodology for that is below. GNI not Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the main criterion.

According to the scale, the US pays 22% of the total amount of assessed contributions paid to WHO by all its member states. China currently pays 15% (WHA76.8). For the biennium 2024/25, the total ACs due to the WHO is $1148m, so it’s an easy calculation: $252m from the US, $172m from China. WHO’s budget portal and summary document has slightly higher figures: $261m from the US and $175m from China. Unlike the voluntary contributions (VCs) that member states make voluntarily to WHO, if the US wants to continue to be a member of WHO, then its ACs are the price it has to pay – and that’s not up for negotiation.

The decision by Trump to withdraw from the WHO means, of course, that there’s going to be a funding shortfall. When estimating exactly how much that shortfall is, we should be cautious about using a single year of US VCs as being indicative of what the US typically pays or would have continued to pay into the future had Trump not won the election. As of March 2025, the US has paid $450 in VCs for 2024-25, a slightly-above-typical amount (see my earlier post and the figure below). There is also a clear desire amongst the WHO’s members (and WHO’s Secretariat) to return to a pre-Covid budget trajectory. So, I stand by my super-approximate guesstimate that a figure of around $500m total in ACs and VCs per annum from the US to the WHO is about right. Sure, the ACs would increase a bit over time but the VCs are not fixed but contingent on lots of different factors. With that in mind, then $500m would be the shortfall that other donors would have to make up – each year – when Trump exits in 2026. That might sound like a lot to you but it’s less than $3m extra if $500m is divided equally between the other 193 member states.

I don’t think that Tedros is going to go round with a cap/mobile app asking each individual member state to pay $3m, of course. I’m just making the point that $500m is not a huge amount of money in and of itself for member states to cover, if they wanted to. So, what is Tedros going to do about the shortfall? In the short-term, we have been given an insight via a leaked email scooped yesterday by Furlong and further reported by Devex’s Jenny Lei Ravelo. The gist of the email is that there’s going to be a recruitment freeze, travel is going to be strictly curtailed with the default being online meetings, replacement of IT will be limited, and major contracts are going to be renegotiated. I’m not surprised that the DG is taking these cost-saving measures. Hey, I work at a UK university, so I’m very familiar with recruitment freezes when budgets are tight. But this decision will likely impact one of the Key Performance Indicators (KPI 6: Quality of work: attracting talent) developed by the Secretariat to keep track of progress on its sustainable financing. It’s also worth noting that over the last ten years, investment in staff has not kept up with the budget increases, meaning that more is being done with fewer resources. The freeze on staff recruitment will add pressure on WHO’s existing workforce.

Travel expenses were $231m in 2023 (6% of total expenses) of which 45% were staff. The average cost of a ticket in 2023 was $1149 and per travel $1766. In 2019, travel costs = 7% of total expenses, so there’s been some improvement here. Taking advantage of digital technology and virtual meetings seems like an easy win to me (Covid showed the world that it could still function without having to get on a plane), but consultants won’t be pleased (21% of total travel costs). The quote that struck me most from the email was this one from Tedros: “WHO’s people have always been, and remain, our greatest asset, and we will do everything possible to support and protect you”. One reason why Amazon shouldn’t ever do global health!

Longer-term, it’s clear from reading WHO’s midway update on financing and implementation of its 2024/25 program budget and its draft 2026/27 program budget that the Secretariat has been thinking a lot about – and has planned for – a Trump withdrawal. The Secretariat is well aware of the risks: “Losing any major donor would create a significant funding gap for the specific outcomes that are dependent on these funds, which the Secretariat would not be able to fill due to limited sustainable and flexible financing” (EB166/26 p16). And it has a clear plan for responding to and mitigating risk that is much more developed and integrated into its strategy documents than the snippets of text in an email from the DG might suggest. For example, there is a whole section of the 2026/27 draft budget detailing WHO’s risk management strategy.

In the context of constrained funding within WHO, it may not be possible to tackle all risks at the same time. The principle of risk-based prioritization will be applied when investing the efforts needed to implement the programme for change. For that reason, the Secretariat will prioritize resources to manage risks that are recognized as critically affecting WHO’s work at the country level. By prioritizing these risks, we can achieve maximum impact at the country level while prioritizing scarce resources.

The WHO’s Global Risk Management Committee has identified a list of principal risks for 2026/27, with the top five being: unsustainable financing, simultaneous grade 3 emergencies, abuse of power and harassment, fraud and corruption, and sexual misconduct and harassment not prevented or addressed. It will be the Secretariat’s job to prioritise resources and implement systems to manage these risks.

I’ve been asked a few times recently what I think could be the financial impact of a Trump withdrawal from WHO. I always start by emphasising that I’m an outsider – I don’t work for WHO and have no insider knowledge. I imagine that WHO staffers reading outsiders’ accounts of what they do must roll their eyes at our misinterpretation of how decisions are made. That aside, and in no particular order, here are a few things I think/fear might (but hope won’t) happen.

All the hard work that the Working Group on Sustainable Financing did to successfully persuade member states to increase their ACs by 50% by 2030 – a monumental achievement – could be undone if Trump’s decision to withdraw causes other members to walk away from their commitments. WHO is aware of this risk: “the Secretariat is cognizant that such an increase [in ACs] will not be automatically granted”. During regional committee discussions last year, member states re-affirmed their commitment to increasing their ACs, but nevertheless it remains a possibility.

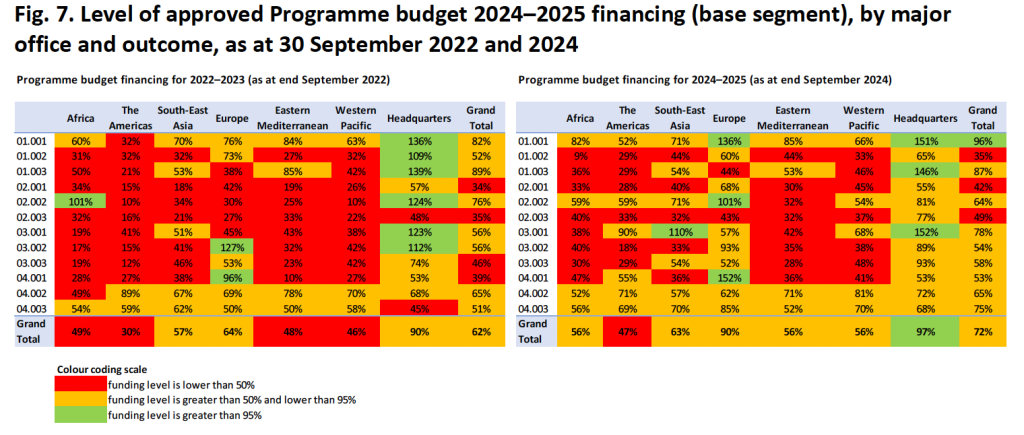

ACs are fully flexible and thus the most valuable to WHO. Generally, they cover staff costs (see Annex 1) but can also plug gaps in under-resourced health priorities. There is evidence that WHO’s so-called ‘heatmap’ is getting greener “largely due to the increase in flexible funds, most of which have been allocated to the regional and country levels” (Figure 7, p10). Without these flexible funds, ongoing efforts to fill ‘pockets of poverty’ across WHO’s health priority areas could dry up.

Because ACs are predictable, more money up front allows the Secretariat to spend its money more quickly. There is evidence presented in EB156/26 that expenditure is increasing earlier in the biennium thanks to increased flexible funding – things are getting done! But that progress is contingent on a constant (and increasing) flow of flexible funding.

Unfortunately, EB156/26 also reports a funding gap in VCs of $564m. This will make it harder to fully fund the base segment, 60% of which is funded by VCs. The report notes that there was high hopes that the recent Investment Round would attract sufficient VCs to fully fund WHO’s 14th General Program of Work, but these hopes were only partially met (less than $2bn of the $7bn required have been raised so far).

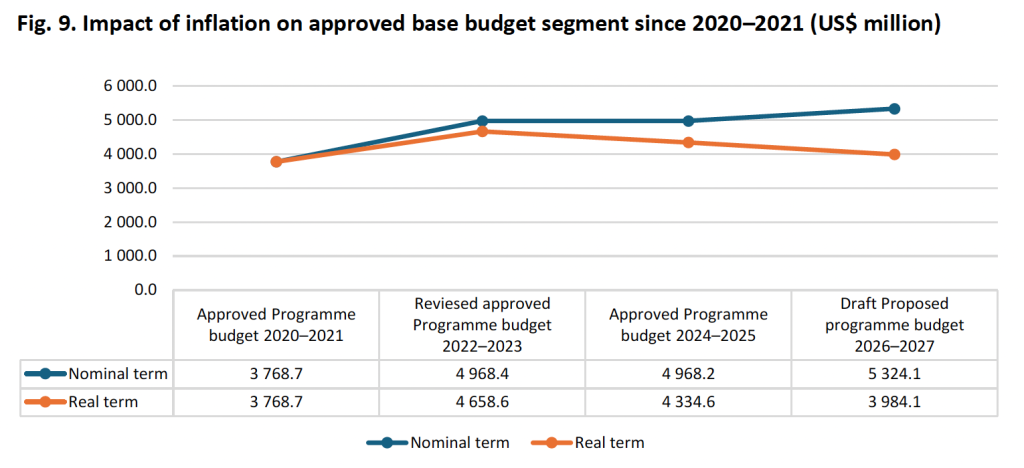

For the first time in a long time, there is an increase in the proposed program budget. The budget freeze could be lifted – yay! The draft 2026/27 program budget that will be presented to member states for approval at the WHA in May is $355m more than the previous biennium. This increase is being justified in terms of inflation. Figure 9 of EB156/27 is quite an eye-opener as it shows that in real terms the base segment of the program budget has increased by just $216m since 2020/21. Nevertheless, the Secretariat is clearly feeling confident to propose an increase. The concern now is that Trump’s withdrawal (and the impending shortfall) might mean that the increase in the draft budget is not approved in May.

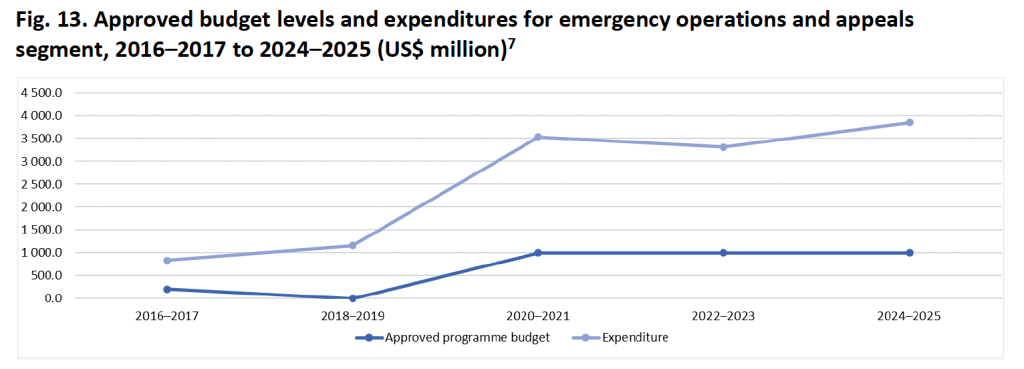

Finally, referring back to the main risks to WHO identified by its Global Risk Management Committee, 2025 is likely to see an increasing number of health emergencies. The 2026/27 draft budget goes to the trouble of pointing out to its readers that there is a “disconnect” between the nominal US$ 1 billion budget line for Emergency Operations and Appeals and the actual amount of funds spent “which has grown significantly”. The figure below is, in my opinion, a good visualisation of the global health polycrisis we are currently experiencing. Member states should be looking hard at this figure because these crises are, sadly, exactly why we need a World Health Organisation. International coordination and cooperation is necessary to respond effectively to these crises, and the WHO is the best arrangement states have to do this. What is concerning, however, is the Secretariat’s reluctance to increase its EOAP budget line above the $1bn, preferring instead to accept the guidance from regional committee discussions “that at this point in time it is wiser to keep the current practice in order to avoid the perception of a large budget increase”. The evidence suggests that WHO will need more money for its EOAP, but budget sensitivity now made worse by Trump means it can’t ask for the money up front to help it firefight emergencies it knows are coming.

Yes, the title of this blog post is a tired play on words. Obviously, the WHO does not need Trump. I could vent my frustrations in this closing paragraph with a long list of expletives describing that human ball sack. But that won’t change the outcome. I think Trump will try to use the decision to leave WHO as leverage to reform the Organisation. If that happens, I hope the DG will resist. What happens next depends very much on what the other 193 member states decide to do. Sweaty global health law professors will tell you that there is no appetite amongst member states to fill any financing gap left by Trump, but I think they’re wrong. I agree with Gordon Brown here: “Member states in each region of the world should step up and make sure WHO is sustainably financed”. As Brown points out, if a World Health Organisation did not exist, we would have to create one. We must not let the one we currently have drift away.

Andrew

One comment on “WHO needs Trump?”