It’s not an easy task tracking WHO funding, especially this year with the fallout from Trump withdrawing his support. I find that the best way to make sense of it all is to write about it. So in this post, I’ll try to bring together the main threads of this complicated story. I summarise five ‘gaps’ in funding/financing: a financing gap in the base segment of the program budget 2024-2025; a funding gap from the withdrawal of the United States from the WHO; a staff salary funding gap; an operational funding deficit; and a funding gap in the program budget 206-27. The figures associated with each are not cumulative (i.e. adding the five gaps together does not give you one overall mega-gap), but they are inter-related.

If it’s possible to summarise what’s happening in a couple of sentences, I would say that the headline is that the Secretariat is facing a $450m financing gap in the base segment of the 2024-2025 program budget i.e. expenses are exceeding revenue. The main reason for this gap is that the United States’ outstanding assessed and voluntary contributions for 2024 (which together total $450-470m) are unlikely to be paid, and the WHO has formally written this loss into its accounts. As of March 2025, the base segment of the 2024-2025 program budget was 96% funded, which still leaves 4% or $210m to fund. If you combine that funding gap and the US shortfall, you get approximately $660m. This will hit salaries hard, and we’re seeing a big hole in the staff salary pot of money – $317m to be precise. However, it’s a bit more serious than that because of the lack of flexibility in funds that the Secretariat has at its disposal. This is resulting in an operational funding deficit of $580m. Given the urgency of the situation, the Secretariat requested and Member States approved this week a suspension of financial regulation VIII 8.2. This has allowed the DG to use up to $410m of the Program and Support Costs Fund (a Fund normally reserved for management and administrative support) for staff salaries. Although I’m now hearing rumours to the contrary, the latest audited financial statement concludes that “the liquidity position of WHO was found to be sound with the current assets being more than three times its current liabilities” (A78/25, p8).

Gap #1: Financing the 2024-2025 base segment – a $450m deficit

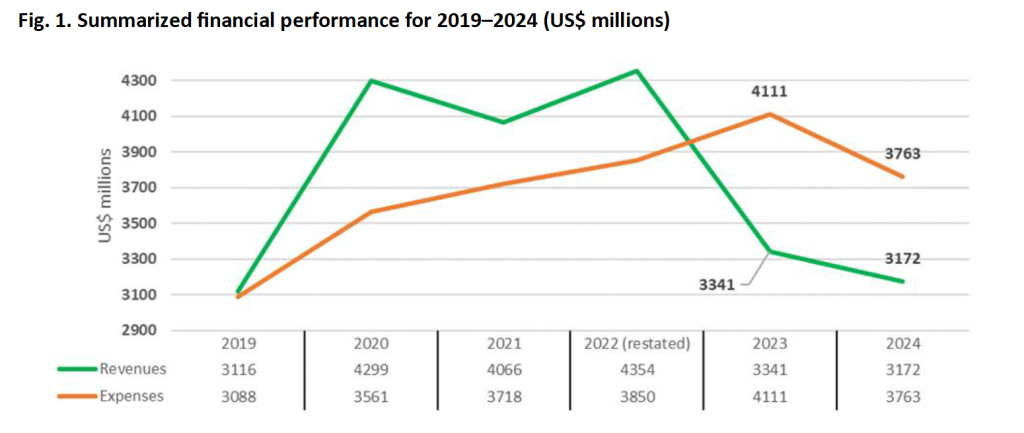

Moving from the general to the specific, let’s start with a few known knowns, beginning with revenue and expenses. For anyone interested in tracking WHO funding/financing, the best document to read is the WHO’s annual audited financial statements. These are published just before the World Health Assembly. The audited financial statement for the year ended 2024 (A78/18) was published on May 8th, for example. Below is a useful summary graph from that document that maps revenues and expenses for the past six years.

The WHO receives revenue from four main sources: Member States’ assessed contributions; Member States’ and non-State donors’ voluntary contributions; in-kind revenue; and ‘other sources’ (nothing sinister, just things like fees for services such as pre-qualification fees, hosting fees from organisations like UNAIDS, rental income, etc). That revenue covers expenses such as: salary costs ($1293m in 2024); contractual services ($1279m); transfers and grants ($423k); general operating expenses ($284k); medical supplies/materials ($261k); and travel ($206k). Most of the revenue goes to finance the program budget – $2990 of $3172 in 2024.

You can see the problem though: revenue dropped precipitously since 2022 but expenses continued to rise, began to fall in 2023, and are now falling sharply. You could describe this as a funding or a spending problem. Bjorn Kummel, who leads the Global Health Unit at the German Federal Ministry of Health (and who was Chair of the WHO’s Working Group for Sustainable Financing), criticised the WHO Secretariat at a side event organised by the Geneva Graduate Institute this week for not anticipating – and not making contingency plans for – a drop off of revenue after the Covid 19 pandemic. The result of all of this is a funding deficit of $450m.

The eagle-eyed amongst you will notice that $3763 – 3172 is $591m not $450m. That’s because the WHO also benefitted from finance revenue to the tune of $141m ($591m – $141m = $450m). You can see these workings out in the Financial Statements at a Glance (p6) or in the Schedule III Financial overview table on p96 of the audited financial statement. What Fig. 1. above shows is a pandemic funding arc where funding at the end of the pandemic has, almost exactly, returned to its pre-pandemic levels. Whether you want to describe the $450m gap between expenses and revenue as a ‘crisis’ is up to you. Either way, I think there is an important lesson to learn here for IOs preparing to fund the next pandemic.

Why is there a financing gap, and what is the Secretariat doing about it? As I’ve already mentioned, the graph shows a dramatic reduction in funding between 2022 and 2023. The WHO went from a net surplus of $598m in 2022 to a net deficit of $522m in 2023 (A77/20 p9)! The main driver of this deficit was a steep reduction in voluntary contributions ($911m). The Secretariat was able to finance this gap by revenue received in 2023, unspent revenue from previous years (aka ‘the accumulated net surpluses’), and by a significant increase in finance revenue ($247m – see 5.4 of A77/20 for a table that explains where this revenue comes from – mostly investment revenue. On investment revenue, see Fig 17, p21 of the audited financial statements A78/18). So, the $522m gap was filled but the alarm bells were beginning to ring (or should have been).

Gap #2: The United States withdrawal – a $453-470m hit to the WHO

The timing of this story is an interesting one, and a cautionary lesson for people like me who are following events closely. Note that the audited financial statements were published on the 9th May, just a couple of weeks before the WHA. Go back a few more weeks – to April – and the only document you had to go on was document A78/INF./3 Voluntary contributions by fund and by contributor, 2024. That document appeared to be confirming that the United States had paid its voluntary contributions for 2024 – hurrah, I thought! Things weren’t looking too bad.

But pace Andrew! As the audited financial reports now document, the United States withdrawal from the WHO has thrown a major spanner in the works. We knew that this was coming, but it’s only now formally accounted for in this document. Here’s the key text: “an increase in the allowance for doubtful accounts receivable, primarily as a result of a series of executive orders by the United States of America from 24 January 2025, which resulted in a decrease in net revenue for assessed contributions and voluntary contributions of US$ 123 million and US$ 330 million, respectively”. The audited financial reports explains the significance of the US withdrawal in detail right at the end of the report (70) and it’s worth quoting in full:

“Based on the information available at the date on which the financial statements were authorized for issue, including the issuance of the executive order, along with that of subsequent “stop work” and “termination” letters, the Organization deems it unlikely that the amounts currently outstanding from the United States of America are to be received. These have therefore been included in the allowance for doubtful accounts receivable in full; further details are given below for assessed and voluntary contributions” [my emphasis].

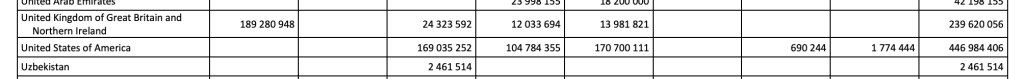

It’s probably also worth pointing out that in the quote above, the figure for the amount that the US owed in assessed contributions is $123m (p11) whereas later in the report it is $132m (p70), and the figure above for voluntary contributions is $330m while later in the report it is $337m. So, I’m going to say that the amount is somewhere between $453-470m. You’ll also have noticed that in the voluntary contributions image above, the total for the US is $446.98m. The audited financial reports document has revised this to $403.7m and adjusted it to $337m to account for $66.5m received from the US since 31st December 2024.

The bottom line is that the US withdrawal has – essentially – resulted in the WHO ‘writing off’ at least $453m of funding and possibly as much as $470m. It’s important to note that this amount is incorporated into the $450m deficit for 2024, it’s not additional to it. But what it means is that all the benefits from gains in increased voluntary and assessed contributions from other Member States – the flexibility and predictability – has been wiped out. This is how the WHO summarises it:

“Assessed contributions, the most flexible funding, accounted for US$ 470 million of total revenue in 2024, down from US$ 494 million in 2023, primarily due to the increase in the allowance for doubtful accounts receivable. In relative terms, assessed contributions represented 15% of total revenue in 2024, no change from 2023″ [my emphasis].

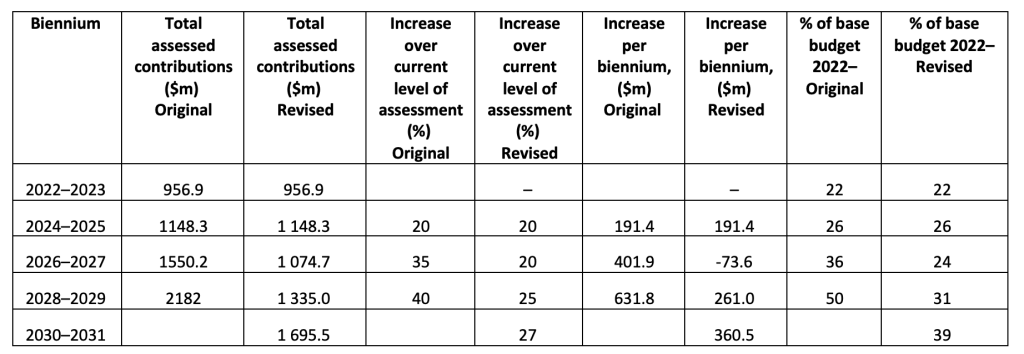

It was very good news that Member States this week approved a second tranche of assessed contributions for the program budget 2026-27. But what is perhaps not fully understood is that the US withdrawal will impact the other Member States’ aspirations significantly. The Secretariat knows this, of course, and has even produced a handy table summarising the revised AC increases (Table 12 of A78/6). It’s sad to see how the original aspiration of a 50% increase in ACs (50% increase of the 2022-23 base segment – $4364 – by 2030-31) has been compromised by the US withdrawal. The table below compares the revised figures from that table with the original figures approved by Member States in 2023 (see A75_REC1 p68). If you look at the 2nd and 3rd columns, you can see that if everything had gone as hoped, and the US was still with us, come 2028-2029 the WHO would funded with $2182m of assessed contributions (the most flexible funding). As is, the WHO is now looking at only $1335, assuming further assessed contribution increases are forthcoming.

Gaps #3 and #4: How a $210m budget gap plus a $453-470m hit from the US can lead to a $317m staff salary gap and a $581m operational funding deficit.

As of 31st March 2025, the 2024-2025 budget of $4968m was 96% funded, although note that this includes $198m of ‘projected’ voluntary contributions. A 4% gap sounds like nothing but actually equates to $210m. As you can imagine, it’s therefore disastrous news that Trump has decided to withdraw from the WHO, taking with him the $453-470m he owes the Organisation. As Tedros notes in his report Financing and implementation of the Programme budget 2024–2025 (A78/19): “The Secretariat [is] fully aware that this reduction poses a risk to the delivery of the Programme budget” (p3).

The main impact of both the program budget deficit and the Trump withdrawal will fall on staff salaries. But the problem goes wider than that to impact the operation of the budget. The media has been reporting a figure of $600m, and I guess it is easier to round it up from $581m reported in the official documents. Here’s how the Secretariat describes the problem:

“the conjunction of the above points [program budget deficit and the Trump withdrawal results in a forecast salary funding gap of US$ 317 million for occupied positions (US$ 581 million aggregated operational funding deficit including activities). This operational deficit differs from the high-level funding gap of US$ 210 million (as measured against the approved budget), mainly owing to the largest portion of funds available being highly specified. Both financing and operational deficits triggered the introduction of immediate cost-containment measures and a prioritization and realignment process for the Proposed programme budget 2026–2027 with a view to defining a sustainable and fit-for-purpose WHO”. [my emphasis]

As is well known, the Secretariat has embarked on a series of cost containment measures to address the funding gap: travel restrictions, a freeze on selected procurement activities, not replacing retiring staff, etc. These measures haven’t been enough, and so – in the cold language of WHA documentation – further measures were necessary, including “major organisational redesign, improving horizontal alignment across the three levels of the Organization, and downsizing the workforce across all levels based on prioritisation and realignment” (A78/19 p11). But even this isn’t sufficient, at least not immediately, which led to ‘last resort’ measures such as including for approval a draft decision suspending Financial Regulation VIII, 8.2 (A78/17 Add 2). This was approved by Member States this week and means that the DG can use the Programme Support Costs fund “to reimburse expenses beyond indirect costs up to a maximum amount of US$ 410 million, to cover the indemnity costs and salaries needed to ensure the financial sustainability of the Organization”. The DG will be able to use this fund until mid 2026 but note that $410m is not enough to cover the $581m operational deficit.

Gap #5: Funding the 2026-27 program budget – $1.7bn

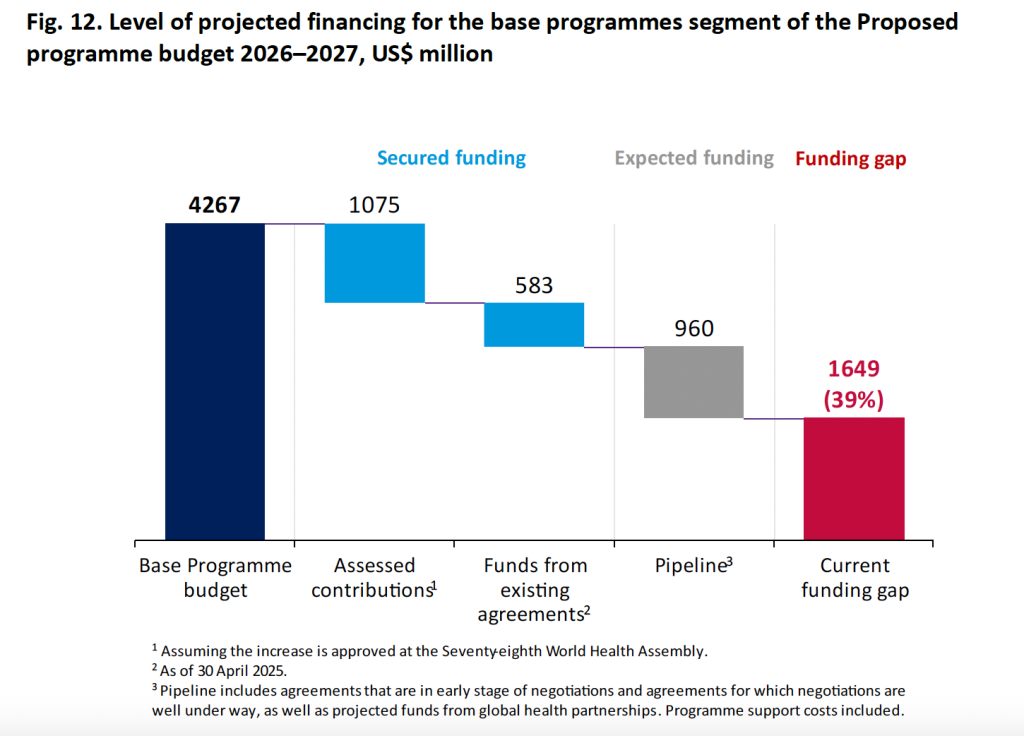

I wrote about this gap in a previous post but it’s worth reviewing it in the light of events at the WHA this week. Here is the key figure from the Proposed (now approved) Program Budget 2026-2027 (A78/6). The good news is that a 60% funded budget at this early stage in the funding cycle is pretty incredible. Previous biennial budgets were nowhere near as advanced.

Just to be clear, and by way of a reminder, the $4.3bn is referring to the base segment of the program budget. Member States approved it this week without any objections. I watched the proceedings and I was struck by how they all seemed super happy with the actions of the DG. Of course, the budget is a significant reduction from the budget discussed at the Regional Committee ($5687m), which became $5324 proposed by the Secretariat, which became $4900m at the recommendation of PBAC, which then became $4.3bn via a March 2025 announcement from Tedros.

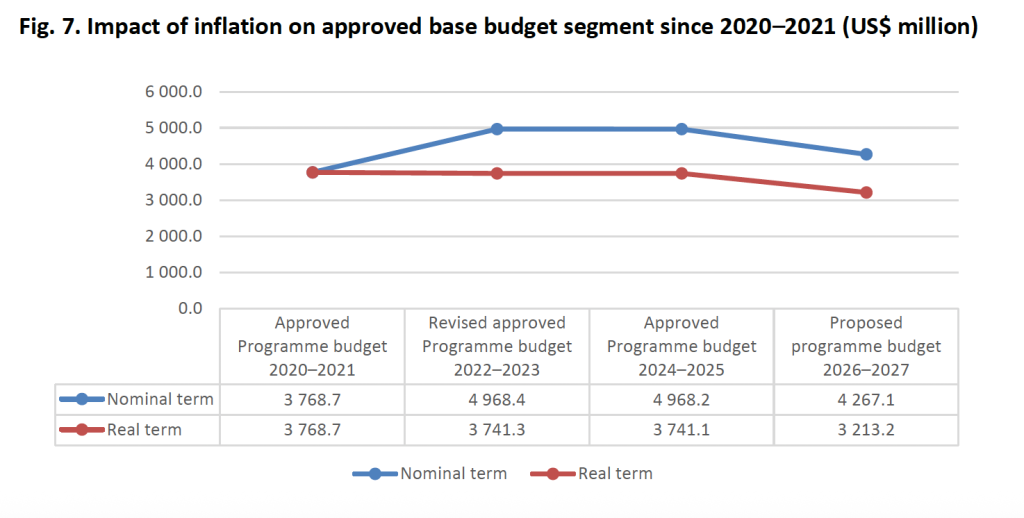

As I’ve pointed out before, you could see this as an increase of approximately half a billion $$ over the 2020-2021 base budget if you wanted to salve your feelings of existential dread – whatever WHO did then, it can do again. But you can also lament the fact that ‘growth’ seems to be all-but impossible for WHO – a bit like that play where it proves impossible for any of the characters to leave the house not matter how hard they try. And you can express grave concerns – as Helen Clarke did yesterday at a side event hosted by the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research – at the devastating speed of the cost containment measures (6 months rather than 6 years) and the impact that is having, and will have, on WHO’s workforce. AND you can underline the point – as PBAC did in February – that the approved base budget of $4.3bn is worth $1bn less in real terms if you take into account inflation. Here again is the important figure from the Program Budget document linked above.

There’s a lot of talk in Geneva this week about how the world has changed – less international aid for health; the wealthiest donor no longer contributing to global health, period; more actors all competing for a diminishing pot of money; countries beginning to think seriously about aid independence. Ergo, the argument then seems to suggest, a leaner WHO that focuses on its comparative advantages (normative work, technical assistance, convening capacity) would be better placed to navigate these changes. But then the WHO DG drops this depth charge into the water:

“an organization working on the ground in 150 countries, with the vast mission and mandate that Member States have given us, US$ 4.2 billion for two years – or 2.1 billion a year – is not ambitious, it’s extremely modest. I hope you will agree with me, and I will tell you why: US$ 2.1 billion is the equivalent of global military expenditure every eight hours; US$ 2.1 billion is the price of one stealth bomber – to kill people; US$ 2.1 billion is one-quarter of what the tobacco industry spends on advertising and promotion every single year. And again, a product that kills people. It seems somebody switched the price tags on what is truly valuable in our world”. (Tedros addressing the WHA, 19th May.)

It seems to me that in a world increasingly characterised by war, with a narcissistic madman presiding over the United States, with a world rapidly warming beyond 1.5C, and a concerted, deliberate attack on science and learning, we need an appropriately (i.e. more funds not less) funded WHO now more than ever. Member States can afford it but are using the ‘changing world’ argument as an excuse not to spend their money where it’s needed most.

Andrew

2 comments on “Mind the gap! Tracking WHO funding.”