This is the title of a webinar I’m talking at on Wednesday 16 July hosted by PHM, TWN and G2H2. You can register here. The general focus of the webinar is to explore the consequences of the budgetary contraction that the WHO is now experiencing for people/communities, health programs, and WHO’s ‘core’ mandate. These are not easy questions to answer and I’m not necessarily the best person to answer them: you would need to ask program managers within the WHO these questions as they would be able to tell you directly what a reduced budget means in operational terms. My contribution to the debate is a familiarity with the WHO budgets, a broad reading of the historical records, and some understanding of the role of International Organisations (IOs) such as the WHO in the context of International Relations. The usual caveats apply: I’m not an accountant (neither the Andy Dufresne nor the Christian Wolff varieties) so could very easily be misinterpreting the budget data. Sometimes the data within the documents is contradictory; sometimes the accompanying text is opaque or ambiguous. I don’t have Raoul Thomas’ mobile on speed dial. All of this means that I can only give you a partial answer based on some knowledge and some experience. That aside, below are some main points that I hope to cover in my presentation on Wednesday.

History matters

The best resource for understanding why the WHO is facing a funding crisis is Nitsan Chorev’s book The World Health Organization: Between North and South. Fiona Godlee wrote a great series of editorials on WHO in the mid-1990s while an assistant editor at the BMJ. Thankfully, I don’t have to link to all of them because Gavin Yamey does that in his 2002 article Have the latest reforms reversed WHO’s decline? One further resource I would recommend you read is a document produced by the US Government Accountability Office in 1977 titled US Participation in the World Health Organization Still Needs Improvement. What do these documents tell us? The message is quite simple: because wealthy Member States like to control the amount of money they contribute to International Organisations, they constantly push for financial reforms. And because IOs’ management structures and systems (e.g. the WHO’s Executive Board) can work to impede wealthy Member States’ influence, Member States also constantly push for managerial reform. The bottom line is 1) there must be a strictly regulated amount of money going to IOs, and 2) the best way to manage the funds is to make the relatively fixed amount of money that is circulating work more efficiently. This is the ‘reality’ within which the WHO Secretariat operates and it is an immense source of tension for Director Generals. It’s interesting to compare Mahler in 1987 with Tedros at the WHA a few weeks ago. Here’s Mahler raging against the United States’ unpaid contributions to the Organisation:

“What crime has WHO committed against those who are withholding mandatory contributions? Surely it cannot be the influence of commercial lobbies who falsely believe the WHO is blocking their expansion…What crimes then has WHO committed? That it has saved them more than they have ever contributed to WHO by eradicating smallpox? That WHO has taken the international lead in the battle against AIDS…and that it has done so with very meagre means, scrapped from the bottom of the barrel…?”

And here is Tedros, venting his own frustrations about the minuscule budget he successfully wrung out of Member States:

For an organization working on the ground in 150 countries, with the vast mission and mandate that Member States have given us, US$ 4.2 billion for two years – or 2.1 billion a year – is not ambitious, it’s extremely modest. I hope you will agree with me, and I will tell you why: US$ 2.1 billion is the equivalent of global military expenditure every eight hours; US$ 2.1 billion is the price of one stealth bomber – to kill people; US$ 2.1 billion is one-quarter of what the tobacco industry spends on advertising and promotion every single year. And again, a product that kills people. It seems somebody switched the price tags on what is truly valuable in our world.

You will read in Chorev’s book (Ch 5) about the Geneva Group. Although open to any Member State that contributed more than 1% to the budgets of the UN Specialised Agencies, the Geneva Group was primarily a lobbying forum for the US, the UK, Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the Netherlands. The group’s main objective was “to re-establish the proper influence of the principal contributors in the process of programmes and budget preparation in the Specialised Agencies” (quoted in Chorev 2012, p136). The US was a particularly bellicose member, as a UK delegate observed in a report following an Executive Board meeting in 1983: “The American’s…obsession with reducing spending has led them to challenge all, even the most minor, increases” (quoted in Chorev 2012, p137).

Obsessed with reducing the 10% rate of increase in the WHO’s budget during the 1970s, the Geneva Group successfully lobbied for for an annual growth of no more than “a real increase of up to 2% per annum, in addition to reasonable estimated cost increases” (Chorev 2012, p144). As Godlee describes, in the early 1980s the Group demanded a zero real growth of regular budget funds (what we now call Member States’ assessed contributions or ‘dues’). Later, in 1993, the WHO introduced a policy of zero nominal growth (i.e. the Secretariat could no longer factor inflation or exchange rate movements into its proposed budgets). Since the 2010s, Member States’ dues have remained at just shy of $1bn per biennium and it’s only recently that – thanks to the efforts of the Working Group on Sustainable Financing – that there has been a move to increase them. Historically, this has meant that the WHO budget has been made up mostly (upwards of 80%) of extra budgetary or voluntary contributions. Typically, these come with strings attached and donors specify what the funds can be spent on. This leads to all manner of problems, including some health issues receiving much more/less funding than others. And because they are voluntary, there’s no guarantee they will even materialise (or when they will materialise). The Secretariat has worked hard to make these voluntary funds more flexible – introducing categories of funds such as ‘core’ or ‘thematic’ VCs, but it’s still the case that most VCs remain tightly earmarked.

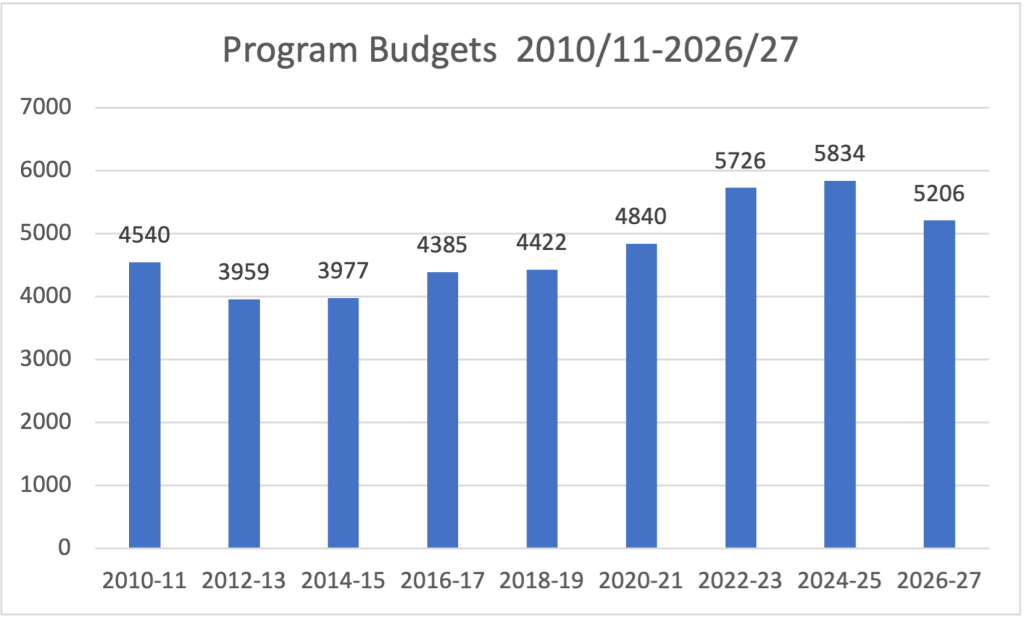

You can see a good illustration of the extent to which this policy has played out in the figure below. The total program budget (includes base segment, polio and special programs but not the Emergency Operations and Appeals budget line, which came into effect for the 2020-21 budget) has never stayed completely true to the principle of zero nominal growth. That’s because most of the funding is voluntary and the principle only formally applies to the assessed contributions. But when you look at the budget across the last 15 years, it’s striking is it not how consistent it is. There was a spike during Covid, of course, but you can now see it returning to levels last seen in 2020. It’s almost as if there is an unspoken agreement amongst Member States that the WHO can have some money, just not too much!. So, looking forward, I would expect the budget to continue to fall until it reaches the mid to high $4bns. I’m not arguing that it should, just that that is what I expect will happen over the coming biennia – unfortunately.

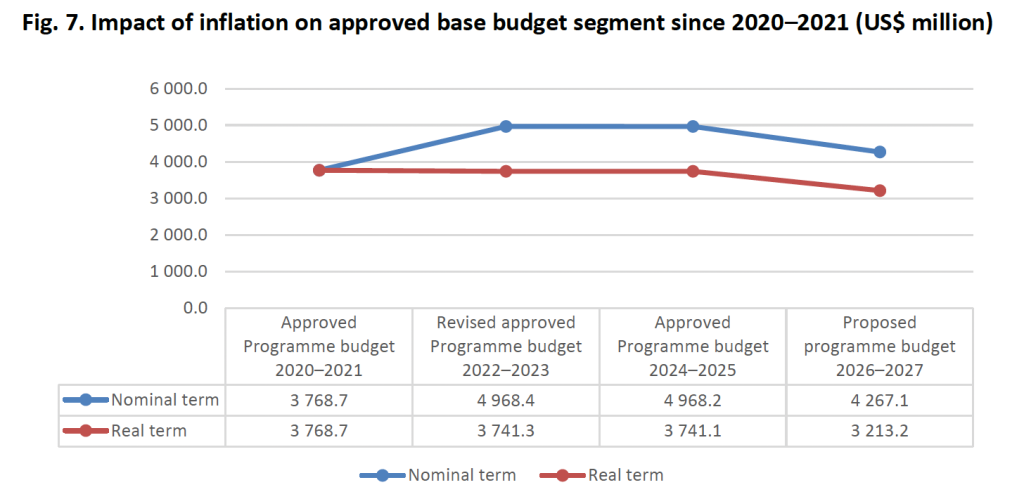

But if you want to see the impact that the ‘unspoken’ zero nominal growth policy is having on the WHO, see the figure below reproduced from the WHO’s 2026-27 program budget. I’ve shared it many times and it shows that, in real terms, the budget is worth far less. As the document notes, the base segment of the program budget would have to be $5bn (rather than $4.2bn) just to keep up with inflation.

So, to wrap up this point about why history matters, what I think we’re seeing is an institutional ‘correction’ whereby the additional funding that WHO received during the Covid pandemic is being clawed back to return to its pre-pandemic trajectory. In my previous post, I termed this a “pandemic funding arc”. And the reason why this is happening is because of a perceived ‘reality’ about the relationship between wealthy Member States and the UN’s Specialised Agencies, in this case the WHO. Over time, a shared understanding amongst Member States has emerged such that the WHO will only ever be allowed to have a modest amount of funding – this is a combination of unconvincing arguments from wealthy Member States that they can’t afford to continually increase their contributions and concerns from the same Member States about the extent of control they wield over IOs. It’s not just wealthy Member States who have bought into this narrative, though. During the 1970s, a coalition of delegates from African, Araba and Asian countries pushed for more money (60% of the total) from the regular budget to be diverted towards technical assistance and services for developing countries. Crucially, there was no expectation that the management of resources would be accompanied by any additional funding. What we are seeing now with the increase in Member States assessed contributions – you’ll recall that these are to be increased over the coming biennia to cover 50% of the 2022-23 base segment by 2030-31 – is reminiscent of the 1970s re-allocation of regular budget funds to technical assistance and services. The unstated assumption now, as it was then, is that there will be no additional funds. If the assessed contributions increase, then expect a corresponding decrease in voluntary contributions.

The scale of the crisis

I’m describing what is happening at the WHO as a funding crisis. Arguably, as per my comments above, one could equally describe it as simply a return to the status quo. People like Helen Clarke of Independent Panel on Pandemic Preparedness and Response (IPPPR) fame have argued that the crisis is actually a crisis of speed rather than a crisis of quantity of funds. Others such as Bjorn Kummel, who was Chair of the Working Group on Sustainable Financing have pointed the finger at Tedros and said, basically, that he should have seen this coming and planned better. In other words, if there is a crisis, then it is one of the Secretariat’s making. Maybe, but that sounds a bit like criticising the captain of the Titanic for not doing a u-turn moments before hitting the iceberg. Anyway, what is the scale of the challenge?

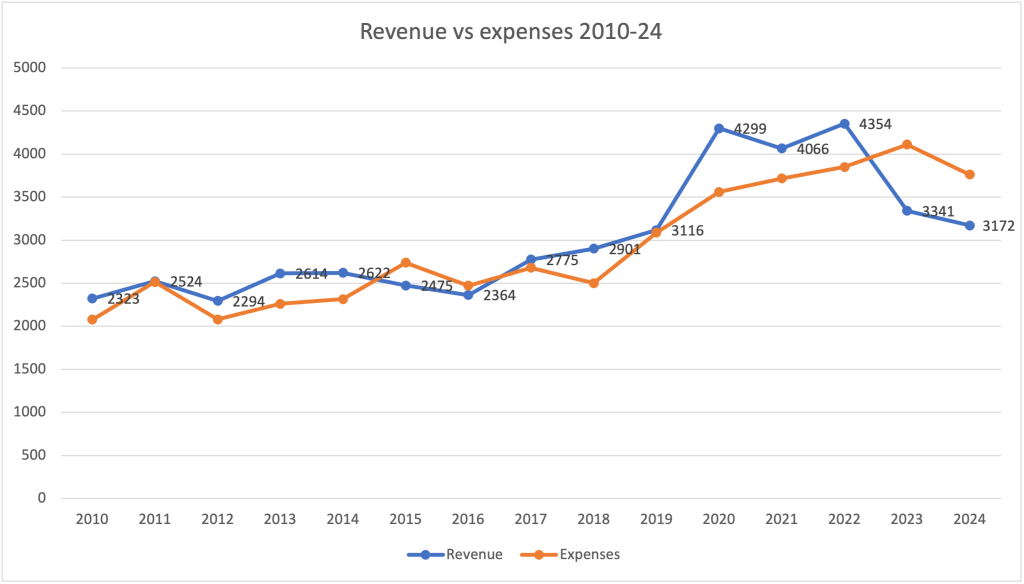

The following figure illustrates how revenue to the WHO has fallen off a cliff since 2022 as expenses have continued to increase. The WHO went from a net surplus of $598m in 2022 to a net deficit of $522m in 2023 (A77/20 p9)! As described in my last post, my understanding is that the funding gap for the 2024-25 program budget is approximately $660m. This figure comes from adding a $450m deficit in expenses vs revenue (thanks mainly to Trump’s withdrawal and the US owing the WHO $450-470m in assessed and voluntary contributions) and 4% of the budget ($210m) yet to be covered by any funds. Some urgent disaster management was undertaken during the WHA to free up some funds by suspending Financial Regulation VIII, 8.2 (A78/17 Add 2). This allowed the DG to use the Programme Support Costs fund “to reimburse expenses beyond indirect costs up to a maximum amount of US$ 410 million, to cover the indemnity costs and salaries needed to ensure the financial sustainability of the Organization”. It doesn’t cover everything but it must have been a relief to get that suspension approved.

And what we also know is that the 2026-27 program budget has been reduced significantly. Tedros announced a reduction in the 2026-27 program budget from the $4.9bn recommended by WHO’s Program Budget and Administration Committee (PBAC) in February to $4.2bn in May 2025. The 2026-27 program budget gives a bulleted rationale (para 60) for this reduction which includes “loss of a major donor” (the US) as one main reason. But it is striking how quickly decisions were made – just a few months between the PBAC and the announcement of a further $600m reduction in the budget! I can only assume that there were some private conversations between the Secretariat and major donors which strongly indicated that a $4.9bn budget would not be approved. But that’s just speculation. Maybe the ghost of the Geneva Group ‘had a word’? Whatever, the fact is that Tedros has slammed on the breaks – the question is whether he’s done it in time to avoid a fatal collision.

Impact on WHO staffing

It’s one thing to point out that the WHO’s budget has shrunk significantly in a very short period of time. But what does that mean for ‘the world’? That’s a big question! We should probably start at the grass roots of the Organisation and then work upwards. A useful document to read when thinking about the consequences of the funding crisis is A78/19 Financing and implementation of the Programme budget 2024-2025. The immediate impact is being felt by the Organisation’s main asset, its staff. Most of the flexible funding that the WHO receives goes on its staff. Expenditure related to workforce (long and short term staff costs and contractual services) = $1038m for the 2024-25 biennium. Staff costs alone = $921m (A78/19 p10). Cost containment measures enacted by the DG this year have saved about $148m but “further and more structural adjustments are needed and are under development” including “major organizational redesign, improving horizontal alignment across the three levels of the Organization, and downsizing the workforce across all levels based on prioritization and realignment” [my emphasis].

Table 3 of A78/19 shows where the salary gap is greatest across the WHO Regional Offices with Geneva HQ worst hit ($159m) followed by Africa ($63m). We know a little about where exactly the axe will fall from this HR document circulated via Health Policy Watch, and also some great reporting from HPW journalist Elaine Fletcher. It’s not clear why Tedros expanded his senior level team to such an extent during his tenure (it’s reminiscent of a swelling of the ranks during Nakajima’s term when he increased directorial positions from 66 in 1988 to 114 by 1994, and doubled senior positions from 7 to 13, as Godlee reported). But we know who the losers will be. Fletcher reports: “WHO’s budget for 2026-27 could reduce the agency’s global footprint by about 20% from a total of 9,463 staff as of December 2024, to 7,525 – with the biggest cuts in entry-to mid-level professional staff who are ranked as P1 to P3”. This is likely to impact significantly on the operational capacity of the Organisation, not just in terms of numbers but also the general morale of those staff who remain employed. That low morale was very evident talking with staff in WHO’s Health Workforce Department during the WHA this year, with many acknowledging that this would be their last Assembly.

Impact on programmes

The General Programme of Work is WHO’s main strategy document. GPW 13 came to an end last year and GPW14 now covers the period 2025-2028. The GPWs are guided by principles and approaches, structured around objectives (that are supported by outcomes), and describe outputs that the WHO will deliver (and be evaluated against). Everything is based on some key assumptions and ‘enablers’ (political commitment, sufficient funding, an ‘optimised’ Secretariat, etc). If those assumptions don’t apply, then the GPW will fail. The question is whether a reduced budget is going to impact negatively on the WHO’s ability to do all of the things it lays out in its GPW14.

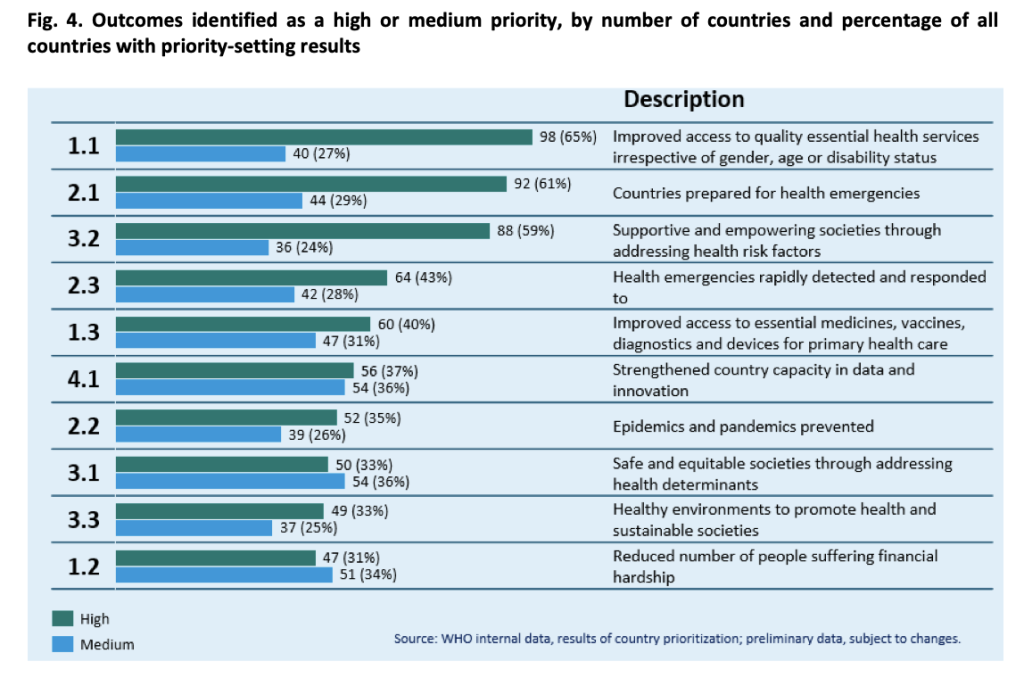

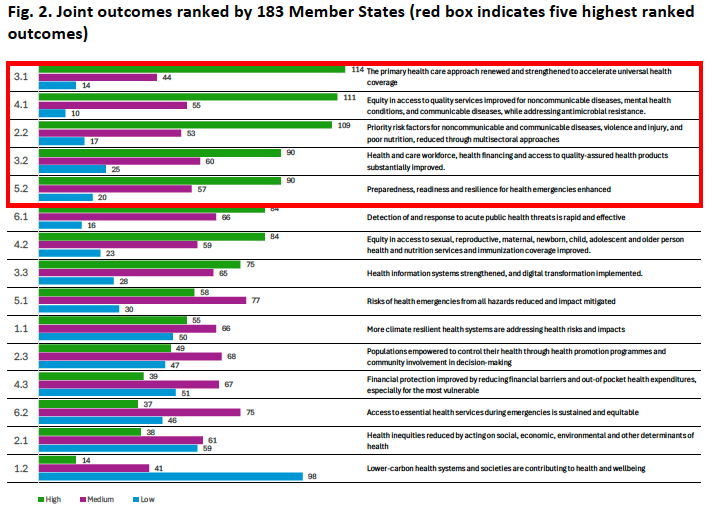

Priority setting became really important as a tool for resource allocation for the 2024-25 program budget. To be clear, the priorities identified by Member States are based on criteria that focus on WHO’s technical ability to assist and not on any judgement about the relative importance of the outcomes.The priority-setting exercise for the 2024-25 program budget identified Member States’ top ten priority outcomes which are described in the table below.

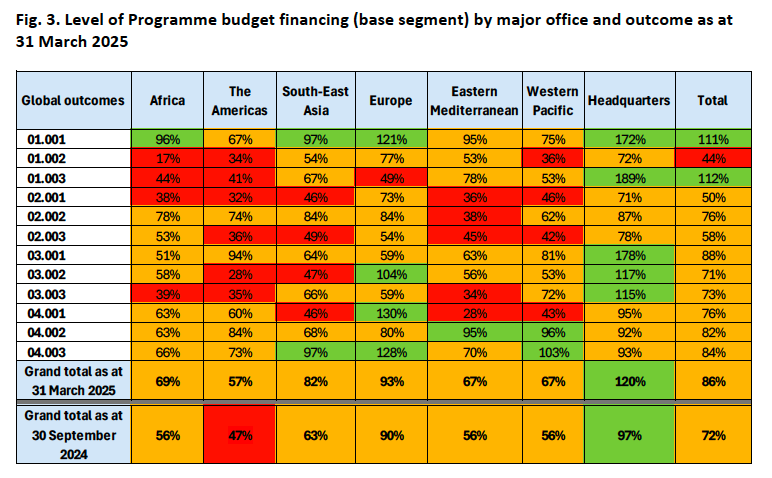

The top five priorities, then, are: 1) access to health services, 2) health emergencies, 3) risk factors, 4) health emergencies (again), and 5) access to medicines/vaccines/diagnostics. As you can see from the heat map below, the health emergencies outcomes are significantly underfunded in five of the major regions. Access to medicines/vaccines/diagnostics is 112% funded thanks to a massive overfund of 189% at HQ level but is significantly underfunded across 3 major regions. Also in the tope ten priorities is 1.2 – financial hardship. This is the least funded outcome at 44% total – and just 17% in Africa. It’s worth recalling that the Secretariat can only re-allocate 5% of earmarked funds across outcomes.

Drawing on the experiences of the 2024-25 priority setting exercise, a similar exercise was conducted for the 2026-27 program budget. Annoyingly, from an academic perspective, it’s impossible to compare outcomes between the biennia 2024/25 and 2026/27 because they relate to different General Programs of Work, were derived using different priority setting processes, and the language of each outcome is radically different. The ‘options’ presented to Member States to prioritise are heavily influenced by whoever penned them. Yes, there was a transparent consultation process, but the Secretariat ultimately wrote the outcomes. This is a classic agenda setting face of power. It allows the Secretariat to magically align everything. The Secretariat want to construct an understanding of what the WHO should do and wants the MS to agree, so it constructs options that can best lead to that outcome. Here is the somewhat triumphant description of the priority setting exercised described in the 2026-27 PB document: “These results reflect a strong global demand for WHO’s technical cooperation in areas central to strengthening health systems, improving service coverage and access and building resilience”.

It’s not obvious how/whether anyone can predict which of the outcomes prioritised during the most recent exercise will/won’t be funded. But we can try. The 2026/27 outcomes are ranked in the figure below.

It is interesting that NCDs are described explicitly in the 2026-27 outcomes (they weren’t in the 2024/25 outcomes). Also – side rant – the outcomes lump so much together – especially 4.1 which lumps together NCDs, CDs, and AMR but the focus is on equity in access. How could that be measured? Anyway, outcome 3.1 focuses on PHC. While not the same wording as outcome 1.3 in the 2024-25 PB, PHC has been significantly underfunded in most regions (but significantly overfunded at HQ level). Outcome 4.1 emphasises equity to access to services, which is more closely aligned with outcome 1.1 in the 2024-25 PB and is well funded across all regions. Outcomes 4.1 and 2.2 both focus on non-communicable diseases. Historically, NCDs are underfunded. By lumping NCDs with everything else, this underfunding could continue but be hidden within an otherwise well-funded outcome. Outcome 3.2 is hard to map onto the 2024-25 PB outcomes but maybe it is allied with 1.2 and 1.3? Both are significantly underfunded. And finally, Outcome 5.2. If this maps to 2.1 in the 2024-25 PB, then it is one of the most underfunded outcomes.

Obviously, we will just have to wait and see which of these outcomes are ultimately funded or not funded. My view is that most of the priority areas identified by Member States as areas of focus for WHO to support will remain those areas that are least funded by the small number of wealthy donors that continue to provide WHO with most of its funding.

Health emergencies

I’m going to focus, briefly, on this broad topic because it illustrates a number of inter-linked issues. You will recall that all of the WHO’s work on health emergencies was brought under a single Health Emergencies Program in 2016 – a decision precipitated by the experiences of Ebola the previous year. The relevant document is A69/30 Reform of WHO’s work in health emergency management. Initially, the program was funded by core funding, a fully-financed Contingency Fund for Emergencies (for rapid deployment), and some crisis specific financing for protracted emergencies. For the 2016-17 biennial budget, there was $334m ‘budget space’ allocated for the program. Since then, the program budget has evolved such that in 2020-21 a new budget line for Emergency Operations and Appeals was introduced with a nominal $1bn approved and which gave the DG autonomy to adjust the amount up or down to reflect the emergencies of the day.

One reason why I am focusing on health emergencies is because of this text in the 2026-27 budget: “Based on the discussions with the regional committees, it is proposed to continue with the practice in previous bienniums of setting the budget for this segment at US$ 1 billion. While Member States acknowledged the current reporting discrepancies, they advised that at this point in time it is wiser to keep the current practice in order to avoid the perception of a large budget increase” (p25 A78/6) (my emphasis). Even though the budget for the WHO’s Health Emergency Appeal for 2025 is $1.5bn, the Secretariat does not feel confident to ask up front for more money to support this aspect of its work because of the current acute budget sensitivity. And it doesn’t feel confident to ask even though it is a demonstrable priority for Member States – based on criteria that include the WHO having the technical capacity to provide support (i.e. it is the right organisation to do the job).

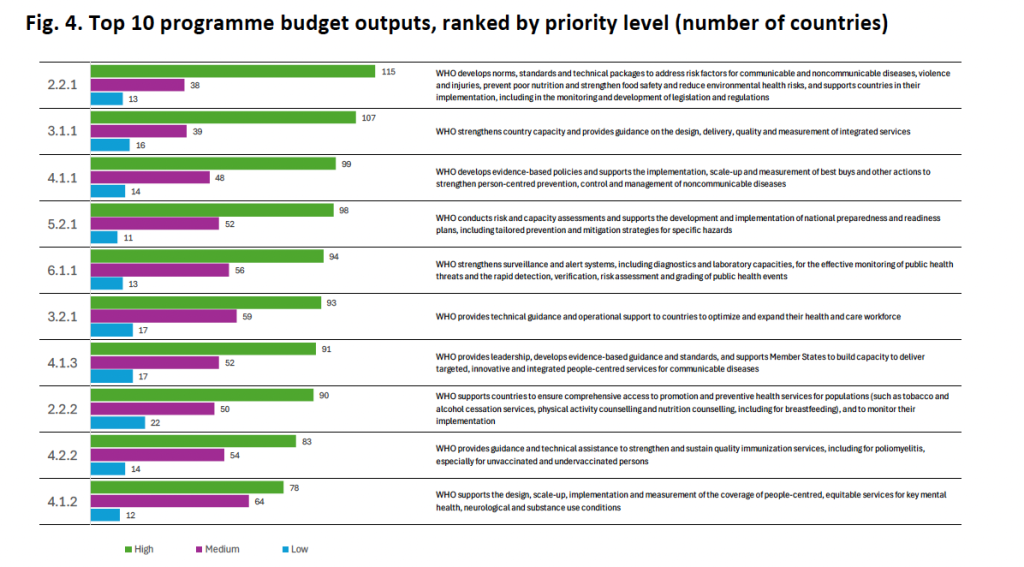

Which brings me to a second point. Inevitably, priority-setting is linked inextricably to debates about what the WHO should – and could – do. Or, if you like WHO’s ‘functions’. I’ve written at length about this issue in a previous post – The WHO that we need. And I describe here how the literature on this topic divides very roughly into three narratives: functional (i.e. WHO should not have more money but stick to its ‘core’ functions); additional (i.e. more money/do more); and progressive (i.e. global public investment). As noted above, the GPWs are structured around objectives, outcomes and outputs. The outputs are what the WHO will do to meet the outcomes. Part of the priority setting exercise was to ask regional offices and HQ to rank the outputs – the top ten are shown below.

The aim was “to identify areas that WHO needs to safeguard and areas that WHO can scale down, delay or stop in

a P1–P2–P3 framework (P1= Essential, must be preserved; P2 = Important, but can be scaled back or delayed; P3 = Consider sunsetting or stopping)”. As you can see, the outputs that are highest ranked also reflect the classic ‘core’ functions of the WHO that were articulated way back in 2006. So, you’ve got output 2.2.1 – norms, standards and technical packages; output 3.1.1 is on guidance; output 4.1.1 is focusing on evidence-based policy, etc. But to return to health emergencies for a moment, the output ranked against this outcome is 6.1.1 – surveillance and monitoring, detection, risk assessment and grading. To my eye, these are a far cry from the kind of activities described in A69/30 – the document that launched the Health Emergencies Program and which has this to say about WHO’s role: “The new Health Emergencies Programme represents a fundamental development for the Organization, complementing WHO’s traditional technical and normative role with new operational capacities and capabilities for its work in outbreaks and humanitarian emergencies” (my emphasis). And it’s a far cry from the kind of work described in the Health Emergency Appeal brochures.

It’s quite likely that I am reading too much into all of this but it feels to me that even though health emergencies are a priority to Member States, and were identified twice in the top priorities for the 2024-25 program budget, nevertheless this area of work is subtly being written out of the main area of focus for the WHO into the future. In 2024-25 we had “countries prepared for health emergencies” and “health emergencies rapidly detected and responded to”, but in 2026-27 we will have “preparedness, readiness and resilience for health emergencies enhanced”. And this will be achieved through surveillance and monitoring, detection, risk assessment and grading. Hmmm.

What does a weakened WHO mean for the World?

Let me begin to answer this question on a positive – and perhaps controversial – note. The WHO was never intended to have an ever increasing budget – this has been capped for decades and what we are seeing now is the budget is returning to pre-pandemic levels. I’ve argued against this for many years, but it does appear to be the case, right or wrong. So you could argue that the WHO is not weakened but is just returning to the status quo informally ‘agreed’ by its wealthy donors. WHO was able to function relatively well with the funds it was receiving in 2019, and could – arguably – do so again. All of the problems it was facing then would continue to apply, of course – pockets of poverty, unpredictable and earmarked funds, etc. And because Trump has decided to withdraw from the WHO, much of the progress made towards increasing the amount of flexible funding has been undermined. So, it feels like we are back to square one. Yes, there is still a bit more flexible funding and there is commitment amongst the vast majority of Member States that flexible funding is desirable. Hopefully, the Investment Round will continue to attract even more flexible voluntary ‘core’ and ‘thematic’ funding, and sufficient funds to fully finance GPW14 (it needs $7.1bn but only has a quarter of that so far). I have also argued previously that the fact that the 2026-27 budget is already 60% financed is a major improvement when compared to previous program budgets at a similar time in the budget cycle. So that’s also good news. My point is that maybe the WHO is not as ‘weakened’ as you might think. I’m not saying it’s great – lots of staff are going to lose their jobs – and it’s immensely disappointing to see funding levels returning to their pre-pandemic levels. Just think what the WHO could do with more money! If I’m being honest, I didn’t come away from the WHA this year feeling that the WHO was in a state of crisis. It could still end up that way, and quite quickly. We have to return to the assumptions that underpin the GPWs – “sustained political commitment” and “sufficient financing”. If those aren’t there, then why would anyone expect the WHO to meet its objectives?

On a less positive note, much has changed geopolitically since the pre-pandemic period. So, the idea that the WHO could return to that era and continue to do what it used to do seems absurd to me. Trump’s re-election and subsequent withdrawal from the WHO, not to mention the impact that the dissolution of USAID has had on global health and international relations more generally, has been an unmitigated disaster for hundreds of thousands of people. The interpretation of findings from a recent study in the Lancet that evaluated two decades of USAID funding is profoundly sobering: “USAID funding has significantly contributed to the reduction in adult and child mortality across low-income and middle-income countries over the past two decades. Our estimates show that, unless the abrupt funding cuts announced and implemented in the first half of 2025 are reversed, a staggering number of avoidable deaths could occur by 2030” (my emphasis). At the time of writing, Trump is asking Zelensky if missiles he provided could hit Moscow. The utter carnage that could ensue following such an act is unimaginable. I struggle often to find an anchor – something that seems secure in such a turbulent world. I feel that the WHO is an anchor – something necessary that we need to hang onto. I can’t imagine a world without it. To paraphrase Timothy Snyder, the WHO is an institution we should care about and take its side.

Andrew