Ilona Kickbusch, Michel Kazatchkine and Peter Piot have written a new Guest Essay over on Geneva Health Files in which they have a bit of a rethink about the role of the WHO in a transformed global health order. Expect more of this kind of commentary in the coming months as the usual players begin to shift their pieces around the chess board. Here are a few modest reflections on their essay.

In their opening paragraph, the authors note that although the Covid 19 pandemic “highlighted longstanding structural limitations in the global health architecture” Trump’s withdrawal from the WHO in January was the main driver of their “fundamental rethinking of what multilateral global health efforts should be”. It’s not specified in the essay which structural limitations the authors were thinking about, but it’s worth re-reading (to take just one example) Else Torreele’s work on The People’s Vaccine project to remind ourselves of the shortcomings of global efforts to govern global vaccine production. You may also recall Gavin Yamey’s description of Covax as “a beautiful idea, born out of solidarity. Unfortunately, it didn’t happen…Rich countries behaved worse than anyone’s worst nightmares”. My point here is simply that a rethinking of multilateral global health efforts was well overdue years before Trump decided to withdraw (again) from the WHO. But, furthermore, you might argue that the limitations of our so-called global health architecture are actually symptoms of limitations further ‘up stream’. To put it another way, what if the architect is flawed?

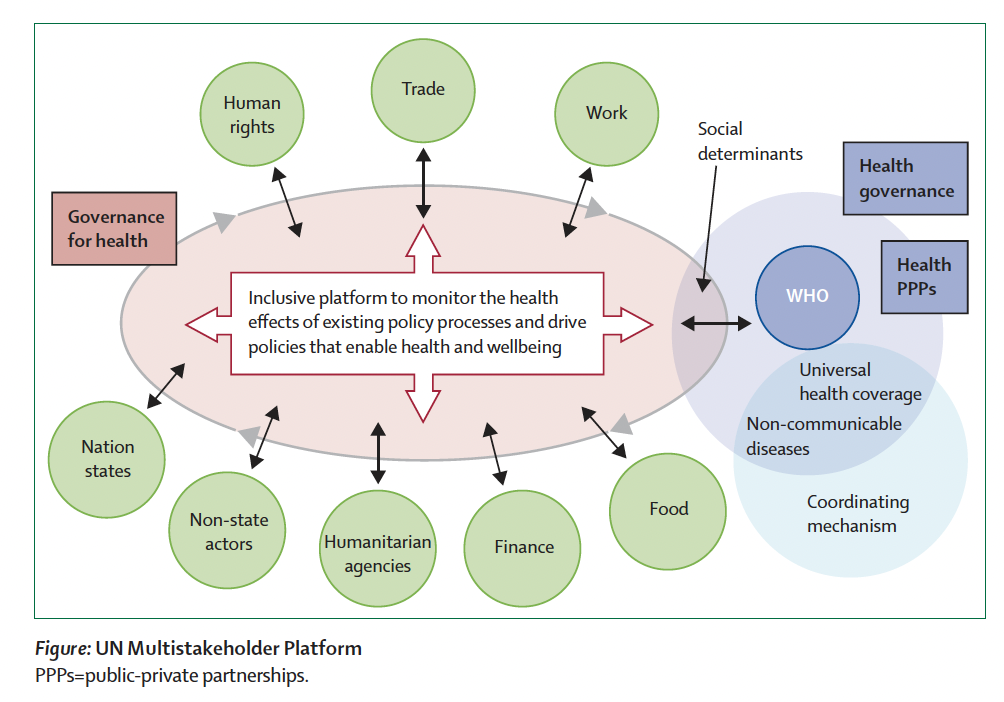

The authors assert that the “WHO is at the core of the global health ecosystem”. It should be, but is it? Does anyone remember this figure from that Lancet paper by Ottersen et al on the political origins of global health? To be fair, the paper was published twelve years ago, but has the Organisation’s relative influence changed so much since then?

That aside, I agree with the authors assessment that the WHO is “one of the most important multilateral organizations for which many countries and political groupings have expressed their strong support”. But it remains a mystery to me why those countries don’t then ensure that the WHO is appropriately funded. As I’ve argued a gazillion times, the WHO’s member states can easily pay more than they do. They just choose not to.

The authors mention ‘geopolitics’, and it’s interesting how they use that term: “Rapid changes in geopolitics further increase the challenges of coordinating health action at the international level”. Equally, though, you could say that geopolitics increases the need for coordinating health action at the international level. Do you want to frame the issue as a need that motivates expansion or a challenge that discourages ambition? Later in the essay, the authors provide a long list of “multiple concurrent challenges” which they use as a preface to make an ominous warning: “Amid this uncertainty, the legitimacy and leadership capacity of WHO – and its future role as a central actor in the global health ecosystem – are at stake”. Or, it’s an opportunity to encourage more funding from member states and for the Secretariat to demonstrate its leadership skills.

Unsurprisingly, talk of funding crises segues uncritically to priority setting. Indeed, one can be used to justify the other. I’m not saying that the authors are doing this, but books have been written on the deliberate manufacture of crises (or ‘shocks’) to bring about change. Personally, I don’t believe that the WHO is currently in a financial ‘crisis’, but we could easily talk it into one by exaggerating the situation. For example, the authors get a bit carried away when they state that the US withdrawal and geopolitics “have forced an accelerated prioritization process within WHO, underscoring both its structural vulnerabilities and the urgent need for strategic reform”. Chill your beans!

The authors are talking about the Secretariat’s internal prioritisation process, which I’ve written about in previous posts (here and here). I don’t really understand why this process isn’t sufficient for the authors. It’s a relatively transparent, inclusive and fair priority-setting exercise that all member states can buy into, and which allows the WHO to maintain its legitimacy. Compare this with the process implied by the authors’ essay, which would basically = me and my mates think the WHO should reduce its core functions to four priority areas. I’m not sure the authors have thought this through. Ironically, they then end the section with a flourish: “We believe in an independent and bold WHO”. Huzzah! But you’re happy to bypass the internal priority setting process by seeking to influence it externally? And isn’t the WHO entirely dependent on its member states’ political and financial support?

Anyway, we’re getting to the main event now, i.e. those areas of “strategic reform” that the authors think the WHO should focus on. They are:

1. Refocus WHO on its core mandate and reduce its core functions to four: setting norms and standards, health intelligence and surveillance, pandemic preparedness and emergency coordination, and convening. That’s actually seven once you separate norms and standards, pandemic preparedness and emergency coordination, and health intelligence and surveillance. I don’t understand why people do this – it’s not four things, it’s seven things: norms, standards, pandemic preparedness, emergencies, intelligence, surveillance, and convening. Conflating PP and emergency coordination is especially problematic in my opinion, as I wrote about in my previous post.

2. Ensure WHO’s financial independence. I’m not going to say that I told you so, but I told you so. We’ll get to my telling you so in a minute. Here, the authors’ arguments are not especially convincing. They rightly note that the 20:80 AC:VC funding ratio “is no longer sustainable”. But that’s why the Working Group on Sustainable Financing worked so hard to get member states to agree to increase their ACs to 50% of the base segment of the program budget by 2030. That took A LOT of work and the ambition has effectively been reduced to a little over 30% increase thanks to the US withdrawal. So while it’s nice to read that the authors’ are proposing “that by 2030, 80% of WHO’s budget should come from assessed contributions”, you have to ask yourself how likely that is to happen.

Here’s how, Andrew: “The 80% target will become realistic and acceptable through a focus on the four core functions proposed above. The overall budget will be decreased significantly through stopping other activities, reducing country offices and cutting back in regional offices”. There are two things going on here. The first is the proposal to significantly reduce the overall budget. This is the ‘do less with less’ argument. Have to admit, I haven’t heard that one before! But I have warned against this rationale and I worry that it will lead to a race to the bottom where the WHO is financed out of existence. Reductio ad absurdum, imagine how little member states would have to give to the WHO if the WHO did nothing? I fear that this is where we would be heading if we accept this line of argument.

The second thing going on is the rowing back on country level support, which is a proposal that goes in the opposite direction to the feedback the Secretariat was getting from member states at the WHA – strengthen country level capacity was the message there. And there are other proposals circulating along the lines of strengthening – not ‘cutting back’ – regional offices. Perhaps more importantly, though, is on what authority are the authors proposing all of this? As per the above point about undermining the priority setting process by wanting to externally influence the decision-making process, now the authors want to unilaterally dictate some new terms of financial engagement? But don’t worry, “this financial reform must be co-led by countries of the Global South”. Ugh – did they even ask ‘the Global South’?

3. Strengthen WHO governance and accountability. Here we go: “In an era of waning trust in multilateralism, WHO governance and accountability must adhere to the highest standards of transparency, ethics, and performance management”. Yadda, yadda, yadda. This is the ‘quid pro quo’ mentality that is undermining WHO/member states’ relations at the moment. But the explanation for ‘waning trust in multilateralism’ – which I think is exaggerated (i.e. mistrust in the WHO is not a perspective shared by most states), btw – is external to transactional arrangements. Trust won’t be restored by WHO’s Secretariat constantly making x or y governance reforms. The Secretariat has been bending over backwards making such reforms for decades at immense cost, effort and stress to its staff, and yet still there are calls to do more. It’s insatiable and achieves little. Governments need to ‘look within themselves’ and ask why they mistrust international organisations; they need to relearn the art of collective decision making; and they need to reconnect self-interest with collective (read global) interest.

The authors end with a proposal to revisit the role of the Executive Board, making the fair point that the Board meetings are becoming quite the grand occasion. But what I’d then like to read are some detailed arguments (supported by evidence) to support claims such as: “The EB has, in practice, become a mini-WHA, failing to operate as a strategic decision-making body. Its role should be redefined to enable rigorous debate and oversight”. It’s noteworthy that the essay has no references and no links to any other literature. For all we know, it could have been written on the bus to work.

I can’t imagine how anyone who works at WHO would feel reading these proposals – demoralised maybe? Unappreciated? Tedros will be delighted, I’m sure, to read this observation: “Leadership reform is also essential. The WHO Director-General must act as a neutral, trusted representative of all Member States—engaging with global health initiatives, UN agencies, civil society, and the private sector”. The implication being that Tedros is or does none of these things. Anything else? Oh yes, just this throwaway at the end: “Independent evaluations should become routine and lead to actionable reforms”. I’m not even going to mention the Boston Consultancy Group.

I remember meeting one of the authors of this essay at the reception desk of WHO HQ. I was introduced and they said ‘oh yes, I think I’ve heard that name’. And then they just wandered off clutching their pass. It turns out that the Greeks needn’t have gone to so much trouble building a giant wooden horse. You just need some photo ID and a lanyard.

Andrew

Please consider donating to the One Dollar, One World campaign

https://www.oneworldhealthforall.org/

You can read about the origins of the campaign here: https://who.foundation/blogs-post/how-a-who-staff-member-turned-the-us-withdrawal-into-an-act-of-solidarity/

I was invited to write a more academicsy version of this post for Geneva Health Files. You can read that version here.

Thanks Andrew

A purely relfective note.

Very useful comments that take me back to the mid 1990s when several governments, academics and NGOs worked hard to strengthen work in what then was still termed “international health.” The drift to global was underway and today is applied uncritically to everything dealing with health outside of the Global North as opposed to the earlier intent: to address transnational threats and opportunities. This included issues like clinical norms and guidelines, research priorities, patent sharing, control of transnational infections, environmental factors, unhealthy marketing that impacted health and was exemplified by the renewal of the IHR and development of the FCTC. We did not know then that with the election of Brundtland we would see the start of 25 years of global health and international health flourishing underpinned by large increases in funding and new institutions. WHO played a key leadership role led by a rare UN leader with courage to act decisively, appoint people based on technical strengths, build partnerships with the World Bank, the new Gates Foundation and more. We do well to reflect on that time and what we have today.

We are in new territory. Funding is dramatically down. Geopolitical reality means that bold global plans will fail where they succeeded earlier. WHO leadership is deeply distrusted. The vibrancy of NGO movements that gave as major progress on HIV/AIDS has dissipated. The potential to find better ways to harness the power of the private sector ethically-something Brundtland constantly encouraged us to do-has been displaced by a very negative approach to most commercial entities .

Meantime the mental health of populations is under stress made worse by the pandemic, social media and economic reality.

What is needed remains unclear. But some elements are emerging. Young bright socially committed young people armed with new technologies must be our biggest hope provided they are imbued with values that favor “us” over “me”.