Quite out of the blue, I was contacted a couple of weeks back by the Secretary-General of the Swiss Association for Science Journalism who invited me to deliver a keynote speech at the Association’s yearly ‘Fall Seminar’. The title of the Seminar is ‘How to cure a health system’, which struck me as an odd way to phrase the problem as it begs the question: ‘from what’? And as I’m not a health systems specialist, I did ask the organisers: ‘Why me?’ ‘Oh, we want someone to provide a global perspective that brings in some geopolitics – you know, to give some context’. I agreed. Journalists are cool, mostly, so who wouldn’t want to hang out with a bunch of them?

Having never delivered a keynote before, I did what all academics pretend they don’t do and asked ChatGPT for help. After a bit of banter with ‘Chat’ about whether or not the SASJ had made a mistake (the AI had apparently reviewed my h-index and raised its digital eyebrow – ‘No, Chat, I’m not pulling your bitcoin, they really did invite me), it relented and provided some pointers on what constituted a ‘keynote’ speech rather than a regular lecture. Let’s see: a keynote focuses on purpose, tone and structure, and it should inspire and energise the audience, give some big ideas and a vision, and provide a unifying, motivating message. Yikes, I’ll get my coat! Oh, wait, rhetoric – I can use rhetoric! Can I swear? Fuck yes! Damn, why haven’t I done one of these before? [Ed. you have to be invited, you can’t just ‘do’ one – it’s not a Ted Talk].

So, the title of this blogpost is the title of my keynote: Does global health have a future? Some reflections on the present. Below is the work I do to prepare for things like this. It’s not what I’m going to deliver: that would be boring. Somehow, I’ll do whatever alchemy lecturers do and convert this dry content into a scintillating oration. I confidently predict that the applause following my keynote will echo for centuries; future global health policy will draw from it extensively; Nordic tales will be based on it [Ed. Nordic? You’re going to Switzerland. Me. Yes, fucking Nordic – do you have problem with that?]

Obviously, it’s a meaningless question: concepts like ‘global health’ are, generally, timeless. And anyway, each time you ask a question about the demise of something, you are basically just breathing life back into its corpse! The phrase ‘global health’ has a wardrobe full of tired old clothes that people like to dress it up in: ‘death’ is one, ‘crossroads’ is another, ‘golden age’ a third (there was a time when academics used to be imaginative with their language). Global health might not have a future if ‘global health’ was nothing more than a meme or a marketing strategy: both these things are vulnerable to political, economic and cultural riptides – meme today, gone tomorrow, you could say. Sometimes, I think global health is just a meme or a marketing strategy – designed to attract students to study something at university. But there are other times when I think that global health is more than that. I’m going to focus on the ‘more than that’ perspective today.

Global health is important because it’s about the health of everyone.

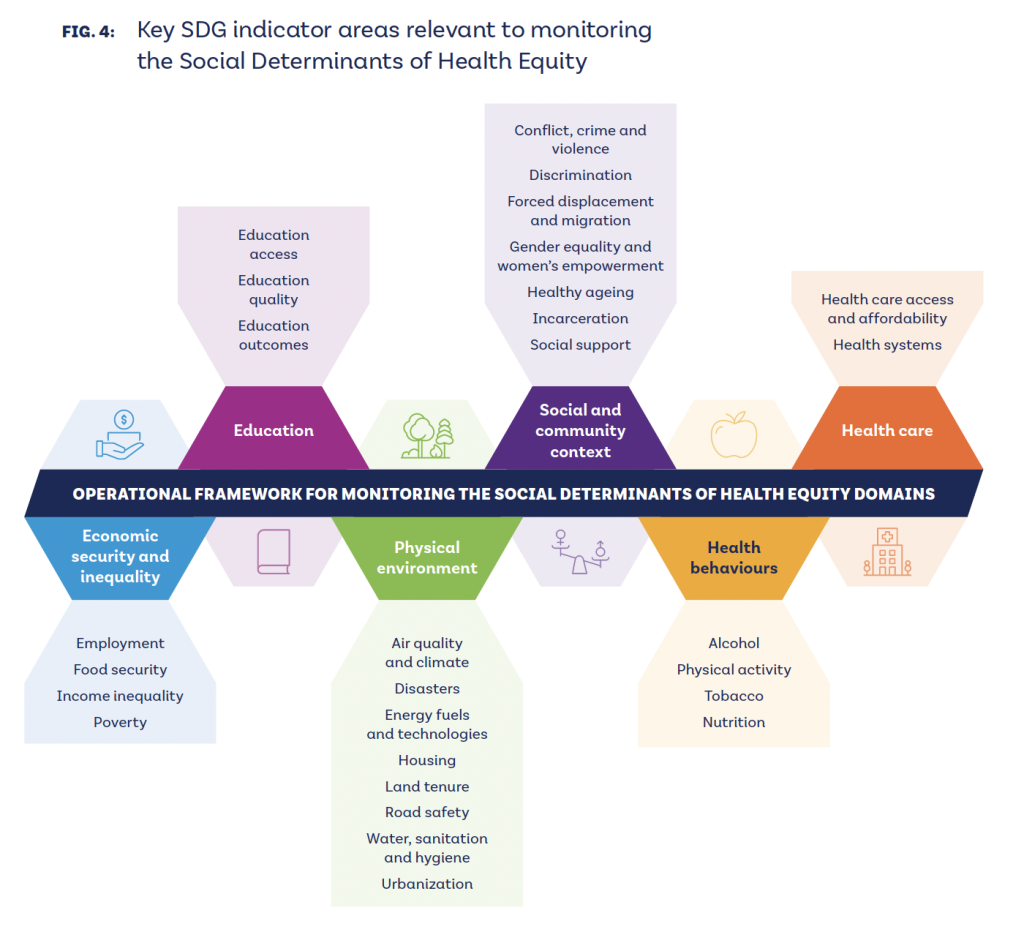

I think what’s important about global health are two things: the fact that it is global and the fact that it is about our health. Yes, I know, genius level insight, right? What I mean is that we are talking about the health of everyone on the planet – the global population – rather than just the health of some of us. The World Health Organisation published a report on health inequity in May this year. Maybe you read it? It noted the many successes we are – perhaps – all familiar with: maternal mortality, for example. It fell by 40% globally between 2000 and 2023, from 328 to 197 deaths per 100 000 live births. That’s progress. But the rate would need to fall to less than 16 deaths per 100 000 live births by 2040 to meet WHO’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Heath target. And it remains the case that women from disadvantaged or marginalised groups are still far more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than women who are less disadvantaged or marginalised – and this applies in countries at all income levels. So, we have a long way to go. There are multiple factors – let’s call them social determinants – that affect one’s health. I’m just stating the obvious, here. Below is a figure from the WHO report that visualises the main ones.

I don’t know which of these is the most important factor. Maybe none of them in isolation. But economic drivers seem particularly important to me. Globally, the divide between the wealth ‘haves’ and the wealth ‘have nots’ has never been wider. It’s a chasm. If Musk were to meet all of the performance indicators recently approved by Tesla, he could access up to $1trillion in stock options. That amount of wealth is simply unimaginable. We all know the extent of global wealth inequality – Oxfam publishes annual reports describing the wealth gap between the wealthiest billionaires and everybody else. Its most recent report found that the wealth of 3,000 billionaires has increased by $6.5 trillion in the last decade – that’s nearly 15% of global GDP. For perspective, the cost of achieving all 17 Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 would cost around $4 trillion. 9 out of 10 people interviewed by Oxfam replied that they would support further taxing the super rich to finance public services. It reminds me of that Rutger Bregman interview at Davos at the World Economic Forum in 2019 where he called out philanthropic interventions as bullshit. His solution was three words: taxes, taxes, and taxes!

There is money to pay for stuff, if we want it. A recent study in which the authors had a go at rethinking the global health architecture argues that their proposed ‘global health nexus’ could be funded by a small % tax on digital services – a transaction that tends to avoid national tax systems. There’s even a word for this kind of tax evasion – base erosion profit shifting (BEPS). And tax could be embedded in membership of the newly conceived global health organisation the authors describe in their think piece (they offer by way of an example a nominal 0.01% allocation from alcohol or tobacco taxation in exchange for reduced membership fees).

Ironically perhaps, given the topic of this talk, wealth inequality per se is itself an important global health topic. Yes, taxing the super rich could be an important source of finance, but since the publication of the book The Spirit Level (revisited in 2024), we’ve known very well that just the fact that inequality exists within and between societies results in lower health outcomes. And not just health outcomes: inequality erodes trust, increases anxiety and illness, and encourages excessive consumption (thereby contributing to transnational crises such as global heating). At the end of the day, inequality dissolves the glue that holds society together: it erodes social cohesion. So when we talk about global health, it’s important because we are talking about the health of everyone, equally and equitably. I mention this now because, at some point I’m going to be asked what do we do? I won’t answer that question specifically, but while I think that it is possible to reform certain things to make something work better (the World Health Organisation, for example), if you really want to improve things – structurally – you need to go way up stream and look at the global economy.

Global health is important because it’s about all health not some health.

Ok, so when we talk about global health, we’re talking about health for all. But when we talk about health, we are also talking about health in the broadest possible terms. This is best expressed in the Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organisation. It’s worth reminding ourselves of the key text because it’s fundamental:

- Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

- The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.

- The health of all peoples is fundamental to the attainment of peace and security and is dependent on the fullest co-operation of individuals and States.

Remember these things: health is holistic – physical, mental and social; health is a right; and if we want it, for everyone, because that’s how the world will be secure, we have to cooperate.

There are two basic challenges to achieving health for all: money and politics

Forty five years ago, at the International Conference on Primary Health Care held in Alma Ata, Russia, delegates made the extraordinary – some might say commonsensical – observation that a sustainable food supply, basic sanitation, and social and economic inequality was the way to address health problems rather than focus primarily on disease-control. The Declaration of Alma Ata articulated a social justice approach to primary health care rather than the medically and technically-focused approach that permeates health care today. If you’re familiar with this story about Alma Ata and comprehensive primary health care, you will know that almost immediately a counter-narrative of selective primary health care was constructed through research by Walsh and Warren, a hastily convened meeting ‘Health, Population, and Development’ at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio conference centre, and UNICEF’s focus on vertical child health interventions. Arguing that comprehensive approaches were a) too expensive and b) too political, the ‘selective’ narrative effectively undermined the holistic and community-led approach envisaged at Alma Ata. I mention this example in passing to make a basic point: IF you think that equality – or inequality to be precise – is a problem for global health; IF you believe that rights are important, and that the right to health is fundamental; and IF you believe – as all the evidence suggests you should – that community-driven health care is best, THEN you are going to – very quickly – face two fundamental challenges – money and politics. People often ask me what global health is all about and I always come back to these two drivers: money and politics.

Financing the World Health Organisation

I’m going to give you two examples to show you what I mean. The first is financing the World Health Organisation. If you’ve followed my blog over the years, you’ll know that I’ve been documenting the WHO’s sustainable financing reforms quite closely and been commenting on the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Organisation. I’m not going to go into too much detail, but these are the headlines:

First, there are structural problems with the way that the WHO is funded: most of its funding comes with strings attached, which means that some health issues are over and some under-financed, and this leads to so-called ‘pockets of poverty’. The funding is unpredictable in terms of when and how much WHO will receive and because it comes from a small number of wealthy donors, the WHO is vulnerable to non-payment (as witnessed with the US withdrawal). These are not new problems, and there have been some successes by WHO in mitigating them – the increases in Member States membership fees, for example. But the problems have come to a head in the wake of the pandemic and the election of a child-man narcissist to the Whitehouse.

Trump has withdrawn from the WHO, leaving a $500m hole in the organisation’s 2026-27 program budget but WHO’s Investment Round has brought money forward with nearly $2bn pledged and $1.3bn signed for the period 2025-2028. On the one hand, that means that WHO’s program budget is currently 75% funded, which is a better position for this time in the funding cycle than WHO has ever been in. On the other hand, as the WHO’s DG Tedros noted last week “we are in a much worse environment for mobilizing resources than we have been in before”, meaning that securing the remaining 25% will be much more difficult than in previous biennia. The WHO is not in as dire a situation as some might have you believe, but we could easily panic and throw the baby out with the bath water in an effort to make things ‘right’ again.

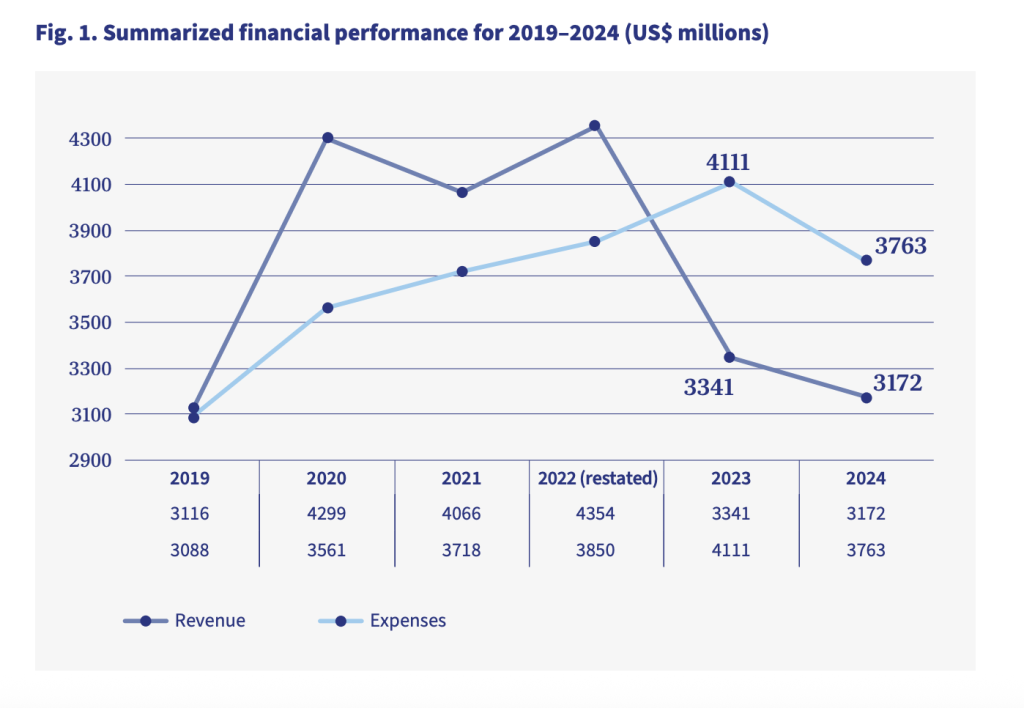

What we’ve seen over recent biennia is what I call a pandemic arc, and (in my mind at least) it explains the so-called crisis that the WHO is currently facing. There’s a figure below of what it looks like. In future pandemics, global health leaders should take note of the trajectory of this arc and plan accordingly. Sad to say, but funders – particularly Member States – are extremely conservative, status-quo seeking funders that will do anything they can to ensure that funding to International Organisations such as the WHO does not exceed a socially constructed funding ceiling.

At the end of the day, the WHO is asking for $4.2bn over a two year period to cover all the things it has to do to lead the world’s multilateral response to health. That is – to quote Voltaire – fuck all! Scholars such as myself like to draw comparisons with money spent on other things to illustrate just how little this amount is, comparatively speaking. Historically, we’ve pointed out that the amount is comparable to the budget of Geneva’s main hospital; more recently it’s been a luxury Boeing jet or – if you prefer – 2/3rds of a nuclear submarine. I like to imagine that $4.2bn is equal to the amount of loose change one might find behind the backs of all the chairs on the planet. The point is that if a Member State complains that its contribution to the WHO is too much while at the same time spending 10x as much on One. Single. Painting – Leonardo Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, for example, which was acquired by the United Arab Emirates in 2017 for $420m – then we should rightly call that out as disingenuous bullshit. What I particularly like about this story is that whereas the UAE/Saudi (the painting was acquired by UAE but paid for by the Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman) contribution to the WHO was money well spent, the painting turned out to be a fake!

The America First Global Health Strategy: an attack on multilateralism

The second example I’d like to reflect on is the recent publication of the America First Global Health Strategy. My first observation? Well, the clue is in the name – America First. Unlike the WHO, which has a global mandate, embraces a holistic understanding of health, enjoys legitimacy from its Member States and hence the authority to make decisions that would benefit everyone, the United States and this strategy document is only about economic self-interest and the health security of its population. It has a very myopic understanding of health – understood in terms of a handful of diseases – and it has no legitimacy (and thus no authority) to impose its will on everybody else. But worse, through this strategy document the United States, or more specifically the Republic Administration, or even more specifically Donald Trump personally, is quite deliberately signalling to the world its/his intention to replace the existing multilateral global health ‘system’ with its own uni/bilateral system. And it’s going to do that through partnerships with individual countries (countries that can’t afford to say no) that promise some short term funding on condition of introducing a raft of long-term health measures that would directly benefit the United States. This is not a ‘retreat’ or a ‘withdrawal’ from multilateralism, as some scholars are politely arguing, it is an attack on it.

Consider, for example the following:

- The WHO is not mentioned once in the Strategy – i.e. the actual leader of global health is written out of US consciousness with Rubio declaring right from the off that ‘The United States is the world’s health leader’.

- In times of emergency, the WHO can mobilise funding in various ways: it has an annual Health Emergency Appeal to support a sustained response to health emergencies; it has a Contingency Fund for Emergencies for acute emergencies; and it has an Emergency Operations and Appeals budget line in its program budget for planning purposes. The America First strategy would bypass this multilateral response to health emergency funding by unilaterally offering to its partner countries (currently un-costed) “surge resources to ensure [an] outbreak is contained”.

- In times of emergency, the WHO advises Member States against introducing broad international travel bans, preferring instead to encourage risk-based public health measures such as screening and contact tracing. During the Covid pandemic, the United States ignored that advice repeatedly. In the Strategy document, countries signing up to a US bilateral agreement would be expected to take its travel advice from United States health experts.

- The United States is very keen to develop its own global surveillance system through its partner countries, apparently preferring this approach to the current WHO-coordinated Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN). Exhibiting a typical ‘have its cake and eat it’ mentality, the Strategy explicitly states that – in the context of surveillance – it will take advantage of multilateral relationships “for targeted purposes, such as when there is not the ability to develop a bilateral relationship with a specific country for the purposes of surveillance”. It doesn’t mention GOARN by name of course because the WHO is persona non grata as far as the US is concerned. There appears to be no recognition in the Strategy that undermining a multilateral surveillance system by replicating it through a bilateral system could weaken that multilateral system, and thus impact on US security in times when it needs to rely on it.

- Following the adoption of the Pandemic Agreement in May this year, an Intergovernmental Working Group was set up to negotiate in a separate Annex a Pathogen Access and Benefit Sharing (PABS) system. The process is being administered by the WHO’s Bureau. It’s a controversial topic but at its root is a desire for better (i.e. quicker, equitable, and more predictable) global surveillance of and response to outbreaks through a legally anchored system of shared pathogen samples and genetic sequence data. Formal negotiations will resume next week. The US has not signed up to the Pandemic Agreement and, through its Strategy document, is seeking to write into its bilateral agreements its own pathogen sharing terms and conditions. The Strategy is very clear about this: “We will engage counterparts in the local government to understand the risks for additional spread and obtain basic genetic sequencing information or physical samples of the pathogen to inform the response and development or deployment of medical countermeasures”. This has not gone down at all well with [checks notes] anybody else. And by anybody else, that includes The Elders. Without naming names, they issued the following warning: “Parallel systems created through bilateral agreements should not undermine the foundations of global preparedness and response being built at the multilateral level. Once multilateralism is hollowed out, it is hard to rebuild”. Emily Bass has taken a ‘first look’ at the model agreement on pathogen sharing the US intends its partner countries to sign. Her conclusion? “Access? Not really. Reciprocity? Not a chance”.

- One of the goals of the Strategy is to “Create a conducive environment for American businesses to deploy their innovative health products and services globally”. It wants its bilateral partners to reduce barriers to entry to the US pharmaceutical industry and one route to that “is ensuring that countries recognize U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved products and promoting regional regulatory harmonization initiatives (e.g., African Medicines Agency)”. Is it a stretch to see FDA approval as an entry point for the US to subvert the much-hated WHO List of Essential Medicines?

The US America First Global Health Strategy fails the two ‘global health’ tests.

All of these measures indicate the desire and intent of the US to replace one system with another – one that reflects its own interests. The Strategy, then, fails the first ‘test’ of global health as it is directed unambiguously towards the health of a specific population (US citizens) rather than the global population. It purports to “keep Americans safe” by developing an unnecessary parallel surveillance system that won’t keep Americans safe; it purports to strengthen the US through an aid program that is repurposed as “a strategic mechanism to further our bilateral interests around the world”; and it will “first and foremost make America more prosperous by helping contain outbreaks at their source, protecting American lives and the American economy”.

But the Strategy also fails the second ‘test’ of global health because health is understood in the document in the most restricted sense possible. Read through the document and check which health issues are described in it. Actually, don’t bother, let me do that for you: it’s a handful of infectious diseases – HIV/AIDS, Ebola, mpox, influenza, Marburg, malaria, TB and polio. That’s what health means to the self-appointed “world’s health leader”. Hang on! What about SARS? What about Covid-19? What about the pandemic? The Strategy document mentions it just once in its forty-odd pages. Second in a list. Behind Ebola. The US is writing its cluster fuck of a pandemic response out of its history books. There is zero mention of any other health issues: nothing about non-communicable diseases, for example. Maternal and child health does, however, get a mention – but in the context of a rebuke rather than anything positive.

At the cold heart of the Strategy is the US’ major concern with inefficiency and waste. Overhead costs are too high, implementing partners have been charging too much, there is too much duplication, and care isn’t integrated horizontally across different services. But do you know what is worse than that? Worse even than waste, theft, and abuse in the supply chain? Well, here’s what really annoys the US Administration:

“Worse still, a violation of abortion-related restrictions in Mozambique was reported to Congress in January 2025 that PEPFAR had funded four nurses who performed at least 21 abortions between April 2022 and June 2024 in violation of U.S. law codified in the Helms Amendment. This deepened concerns that the program had drifted from its original mission [and should not] “cross over into promoting divisive ideas and practices that are not consistent with those of Africa.””

You can see how this development mirrors the comprehensive vs selective primary health care narrative I began with. With this Strategy document, the US would have us return to medicalised and technical framings of health that ignore basic understandings of social justice or the social and economic determinants of health. The Strategy is all about the security of US citizens, and security is best achieved by going to the source, and the source is disease outbreaks in foreign places, overseas. Never mind that the greatest threat to the health of US citizens is home-grown, through the policies of the Trump administration: an administration responsible for the death of >1million Americans from Covid-19 in the last five years; responsible for an obesity epidemic that will likely see 100% of Americans obese by mid century; responsible for turning its back on multilateral action to halt global warming (preferring to ‘drill baby drill’); and responsible for overseeing the worst healthcare system of any high income country – spending more money yet achieving the worst health outcomes.

Nobody wants to join the America First party

Fortunately, the Trump administration is very much an outlier in its selfish, myopic, narrow-minded blackhole of a Strategy. I like the blackhole simile because the Strategy (much like a blackhole) wants to suck everyone and everything into itself. But compare it with what others want – the vision presented by the head of the African Centres for Disease Control Jean Kaseya, for example. In a Comment in The Lancet titled Africa’s Health Security and Sovereignty agenda: a new way forward, Kaseya describes a quite different future to that envisaged by Marco Rubio. Rubio’s US Strategy is supported by 3 pillars: making America safer; making America stronger; and making America more prosperous. Kaseya’s vision is supported by 5 quite different pillars with the African region’s health security and sovereignty at the centre: a reformed and inclusive global health architecture; a continent-wide preparedness, prevention and response unit (Incident Management Support Team) and a sustainable financing arm (the Africa Epidemics Fund); health financing that is predictable, domestic, innovative and blended; digital transformation; and local manufacturing.

How do Kaseya’s and Rubios’s worldviews compare?

- The Africa perspective is regional and global; the US perspective is national and bilateral.

- The Africa perspective believes in solidarity and is supportive of multilateralism (but notes its weaknesses); the US perspective ignores and wilfully underfunds and undermines multilateralism in order to orchestrate an alternate system built around its own self-interests.

- The Africa perspective recognises the wisdom of a regional, coordinated surveillance system; the US wants to create a patchwork of individual surveillance systems propped up by a global surveillance system it pretends doesn’t exist.

- The Africa perspective is about health security and sovereignty; the US perspective pretends to want that too. But you would have to be incredibly naive to think that the US is concerned about African countries’ sovereignty. The US wants Africa’s minerals, and it’s going to get them before China does. It’s a scramble for Africa all over again but wealthy countries are just pretending to be nice about it this time.

- The Africa perspective intends to provide its own, regional, surge capacity, its own sustainable funding, its own digital infrastructure, including an African Health Data Governance Framework because “Africa does not want…to see its health data stored elsewhere”, and establish its own, local manufacturing (“the engine of the second independence of Africa”), be responsible for its own regulatory governance (through the African Medicines Agency) and its own pooled procurement. The end game is a continent that locally produces at least 60% of vaccines, diagnostics and therapeutics by 2040.

- The US perspective has other ideas. Through bilateral agreements with individual African countries (apparently 16 countries have been identified although we don’t have a list of them yet), the US will provide its surge capacity thank you very much, and its idea of sustainable financing is to commit to not decrease current levels of funding to those countries for one year but then rapidly scale back its financial support.

To be clear, the US Strategy is about making its population safe. Another way of putting this might be to say that the ‘function’ of health in Africa is to contribute to the health of US citizens. As far as Rubio is concerned, this is now the job of African health systems. To make sure that those health systems function correctly, the US: “will partner with recipient countries” (i.e those countries dependent on the US for funding) “to develop a streamlined and robust performance monitoring system”; countries will provide the US with “necessary data on emerging threat surveillance, program management, and legislatively required reporting”; and countries will be required to “establish formal transition metrics to track country co-investment” and if they don’t perform, then they won’t get any future money. Another term for all of this is ‘conditionality’, and when countries ‘co-invest’ with the US there will be plenty of conditions attached to “unlock future US funding” around co-financing, developing data systems, and setting program benchmarks for relevant diseases. But more than this, a country entering a bilateral agreement with the US will be expected “to utilise the private sector to the maximum extent practical” because – as everyone knows – “private sector solutions are more likely to consistently deliver lower cost and higher quality services long term”.

It’s not about you, it’s about US

Given all of this, the golden, glowing aim of the US Strategy – that the majority of the 71 US-supported countries will fully transition to self reliance over an agreed time period – is just a lie. Why? Well the simple answer is Pillar 3: Making America More Prosperous. You recall Kaseya’s dream of a continent that locally produces at least 60% of vaccines, diagnostics and therapeutics by 2040? Not on the US’ watch! The US Strategy sees the African continent as one big market for US-based Pharma companies to hawk their diagnostics tests, innovations such as Gilead Sciences lenacapavir, and for American logistics companies to transport commodities. The Strategy is very clear: “The U.S. government will continue to make the purchase of innovative American products a key component of future U.S. health foreign assistance programs”. Oh, and do you really think that the African Medicines Agency won’t recognise US FDA-approved products? The Strategy touts ‘commercial diplomacy’ as a way to promote regional regulatory harmonisation initiatives, but what it really means is an in-road to shaping those initiatives so that they reflect the interest of US companies. Through these bilateral agreements, the African continent will be flooded with American diagnostic companies, healthcare logistics companies, private American pharmacies and clinics, and health data solutions. Market entry is the name of the game, and bilateral agreements is the route to getting it.

I probably need to wrap this up. I started with two global health ‘tests’: is it health for all or health for some, and is it all health or some health? The World Health Organisation reflects the former while the US America First Strategy does exactly what its title suggests and embraces the latter. In thinking about what comes next, we’d be wise not to forget what we have and try harder to make it work rather than throw it all away. This seems to be the reaction to the so-called funding crisis facing WHO at the moment. All Member States have to do is commit to a bit more funding and fund it in predictable and sustainable ways – preferably through membership fees (aka assessed contributions). If that’s really not possible, then look to taxing the wealthy – remember that in the 1950s the equivalent of the US billionaires of today accepted 91% marginal tax rates. The money is there, if we want it.

Look around you. Looking at what is coming out of the United States right now, it’s like the circus has come to town and put the clowns in charge. But not the nice clowns. No, the kind of clowns that hide under your bed waiting with grinning, deformed teeth to drag you under. It’s a horror show. Chief clown Donald Trump is a threat to global health. He is a bully. And if there’s one universal life lesson everyone is told – at home, at school, in books, in films, in music and in art – it’s that you must stand up to bullies. But it’s much easier to do that collectively because that’s where the power lies. The answer to Trump’s attack on multilateralism is to support multilateralism, not abandon it. And you might be surprised to learn that pretty much every other country supports multilateral cooperation: the MIKTA countries do, the G20 does, the EU, AU and OACPS do, and China does – recently re-affirming the central role of the UN in world affairs. So, don’t be fooled by the hype.

Andrew

While ‘taxes, taxes, taxes’ is easy to say, the reality is of course very different. Here’s just one example of the fiasco of international efforts at taxing multinational corporations.