You know the cartoon I mean? It’s the one with the IPCC scientist standing at the front of an auditorium in 1990 warning that “this climate change thing could be a problem” and becoming increasingly anxious at subsequent six-yearly meetings until, in 2019, exasperated at the fact that no-one is heeding his warnings, taps the microphone asking out loud ‘Is this thing on?’ I often think of UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres when I see that cartoon. He must wonder whether anyone is listening to his repeated warnings of impending ecological and climate breakdown.

Here’s Guterres’ latest warning in a Forward to the recently published World Meteorological Organisation’s State of the Global Climate, 2020.

[C]urrent levels of climate ambition and action are significantly short of what is needed… We need to do more, and faster, now…it means radical changes in all financial institutions, public and private, to ensure that they fund sustainable and resilient development for all and move away from a grey and inequitable economy.

Antonio Guterres, WMO 2021. State of the Global Climate. Forward.

It’s not just Guterres who can see the writing on the wall if we don’t sort out the global economy. Here’s the World Health Organisation’s Dr Mike Ryan receiving the Trócaire Romero Award earlier this year (in recognition of his efforts to protect vulnerable communities from Covid-19) and giving this stark assessment:

We’re doing so much, and we’re doing it in the name of globalisation and some sense of chasing that wonderful thing that people call economic growth. Well in my view that’s becoming a malignancy not growth, because what it’s doing is driving unsustainable practices in how we manage communities, how we manage development and how we manage prosperity. We’re writing cheques that we cannot cash as a civilisation for the future, and they’re going to bounce.

Dr Mike Ryan, receipt of the Trocaire Romero Award, Feb 2021.

The state of the global climate

The ‘highlights’ section of the WMO report are summarised in a handy graphic (below) to show the state of the global climate at 1.2C of warming. It gives you an idea of what ‘bouncing cheques’ look like. Imagine what the report would be ‘highlighting’ at 3-4C, which is where we are headed if we continue with the current paltry level of emissions mitigation policies.

It’s going to get worse unless we start reducing our emissions. On the one hand, emissions dropped by around 7% last year, which is the level they will have to drop year in/year out in order to reach net zero emissions by mid-century. But we still emitted CO2 in 2020, just less of it than usual. Consequently, according to the WMO, “Real-time data from specific locations, including Mauna Loa (Hawaii) and Cape Grim (Tasmania) indicate that levels of CO2, CH4 and N2O continued to increase in 2020”.

The United Nations Environment Program’s 2019 ’emissions gap’ report estimated that current efforts to reduce emissions would take us to 27% and 38% over emissions levels required to limit warming to 2C and 1.5c respectively. Its 2020 report is a little more upbeat, noting that a ‘green recovery’ from the pandemic could see emissions reduced by 25% to 44 GtCO2e by 2030 – which would put us “within the range of emissions that give a 66 per cent chance of holding temperatures to below 2°C”. Note that that’s only a 2/3rds chance of keeping below 2C (not 1.5C). That’s the good news.

Covid-19 has helped us to see what a world might look like with profoundly re-calibrated consumption patterns. Do you remember those before-and-after photographs of once polluted cities suddenly clear of pollution? As UNEP tells us, the pandemic is both a wake-up call and an opportunity to do things differently – to embrace a just, ecologically and environmentally sustainable economy.

The road to hell

Unfortunately, if revised economic forecasts are anything to go by, the UK is about to squander that opportunity and return to the pre-pandemic economic model of GDP growth and unsustainable levels of consumption. As lockdown measures are relaxed, the UK is seeing a sharp increase in spending. The Guardian’s Business Live was left breathless with excitement last week at the prospect of a revitalised economy:

We’ve had rocketing UK retail sales for March and PMI data indicating the strongest private sector growth in eight years in April as coronavirus restrictions were eased, which pushed the pound higher. The eurozone shrugged off tighter lockdowns and enjoyed a record manufacturing boom in April, while the service sector returned to growth.

Business Live, 23rd April

This, in the words of Chris Rea, is the road to hell.

With his ‘ten point plan’ for a green industrial revolution, you might think that the UK government was blazing a trail to green Nirvana. Johnson certainly thinks so, boasting to delegates at the Earth Day Summit last week that: “The UK has shown that it’s possible to slash emissions while growing the economy, which makes the question of reaching net zero not so much technical as political”.

But this is the pied piper talking, beguiling you with soothing music. The fact of the matter is that we can’t grow our way out of the climate and ecological crises. It’s simply not possible – I mean, if we are serious about keeping global warming below 1.5C – to reduce annual emissions at the required rate while at the same time growing the global economy by 2-3% each year (the standard measure of a ‘healthy’ economy i.e. for firms to make an aggregate profit). It would be, to use a metaphor from Jason Hickel’s book Less is More, “like shovelling sand into a pit that just keeps getting bigger” (p138).

Buoyed by a desire to “cake have eat” (WTF?!), Johnson’s intended response to the climate crisis was/remains growth. Or, in his words: “Build build build… Build back better, build back greener, build back faster, and to do that at the pace that this moment requires”. True to form, this is what we are going to get. From a fall of 10% growth in 2020, the Office for Budget Responsibility is forecasting 4% growth in 2021 and 7% in 2022.

I see Johnson as less the green Rooseveltian and more the spiteful child who knows the damage he can cause with a well-turned phrase. Recall how, last week, he urged delegates not to regard the international response to climate change as ‘politically correct bunny hugging’, knowing full well that the derogatory term ‘bunny hugging’ would be picked up by the media and the insult would go viral all the same. That was deliberate. This man knows how to shit in your sink.

The UK’s net zero by 2050 target – aka ‘the wrong target‘

Can we return to the UK’s net zero by 2050 emissions target for a moment? This is the basis for Johnson’s cake/eat fantasy. Johnson is waving his signed little scrap of paper from the Climate Change Committee (which recommended that the UK reduce its emissions by 68% by 2030 and by 78% by 2035) like he’s just got a signed autograph from Noel Clarke.

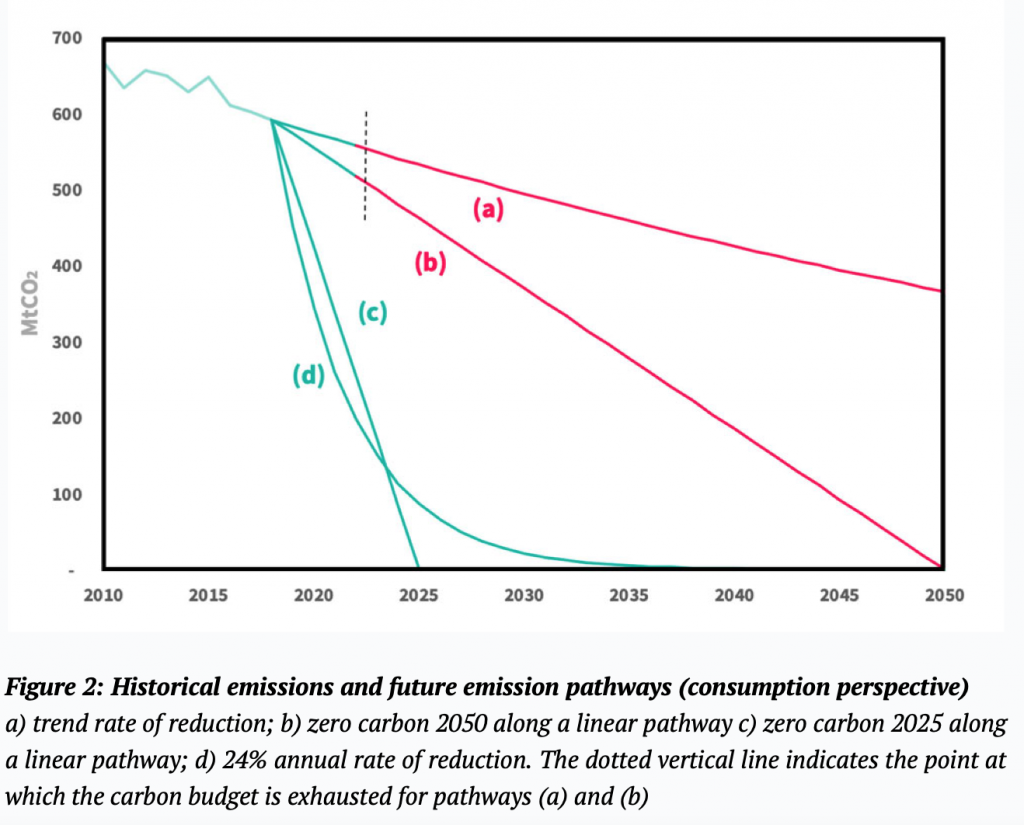

The target is based on a 1990 emissions baseline when the UK was emitting 794MTCO2e. But look, the baseline does not include emissions from aviation and shipping and does not include emissions from consumption of goods and services imported internationally. We know from work by the Centre for Understanding Sustainable Prosperity that if we include what the net zero target excludes then, assuming a linear reduction in emissions, the UK will exceed its carbon budget by 2023. Yes, 2023! If the UK continues along a linear reduction in emissions, year on year, by 2050 it will have exceeded its budget by 13GtCO2. The image below, taken from the CUSP report, might help you appreciate this. Note that whatever falls below the (c) and (d) line is the UK’s actual carbon budget; the difference between that and what falls below lines (a) and (b) is basically the amount by which the UK is blowing its budget. That’s how far over the UK’s carbon budget the net zero target will take us.

What else to say about the UK’s net zero 2050 target? Oh yes, it’s not fair. And by not fair I mean that it doesn’t take into account the really obvious fact that the UK has a historical carbon debt. As with all ‘developed’ countries, the UK started industrialising in the mid 1800s. You would think that any net zero target would take into account a country’s responsibility for the cumulative stock of carbon emissions in the atmosphere and adjust accordingly, wouldn’t you? Looking at historical emissions, the US is rated first with 26% of all historical emissions between 1850-2015, China is third with 12% and India 6th with 3%. If you want to know how the UK’s historical emissions stack up, take a look at the Global Footprint Network.

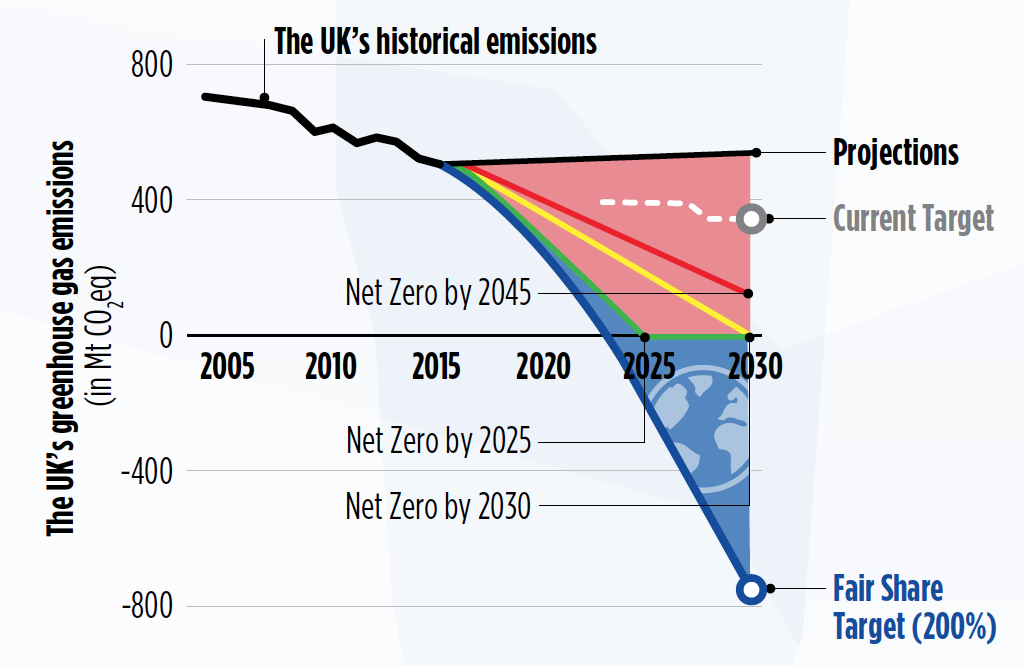

Christian Aid did just that. Remember Johnson agreeing to reduce the UK’s emissions by 68% by 2030? Christian Aids analysis found that the U.K’s fair share of the total emissions mitigation effort (i.e. a share that took into consideration the UK’s historical emissions and its capacity to do more) required globally was around 3.5% of 36 GtCO2eq. That works out to about 1,544 Mt, or 193%, below 1990 levels. That means not just reaching net zero emissions by 2030 but also supporting by a roughly equivalent amount emissions reductions abroad.

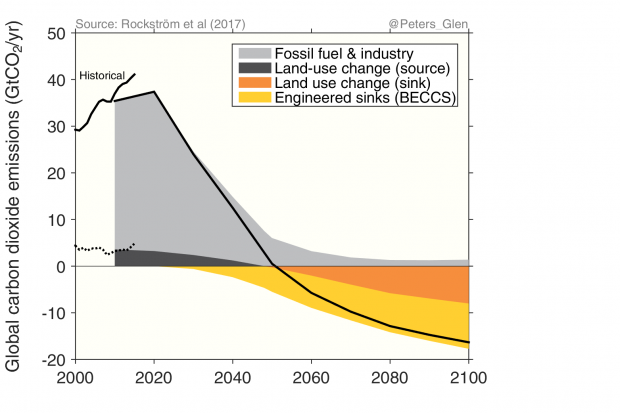

The important thing to remember is that the UK’s target, all countries’ target actually, is net-zero. The ‘net’ problem has been understood for some time, but was described very clearly by James Dyke, Robert Watson and Wolfgang Knorr in The Conversation last week. Take a look at the graph below – it shows you how much emissions have to be removed (either engineered or by natural processes) in order to achieve net-zero. It’s basically everything in yellow and orange:

Dyke and colleagues argue, in essence, that planting trees won’t ‘capture’ enough carbon, BECCS isn’t scalable, DACS (direct air capture) is currently unfeasible and too expensive, and solar radiation management (aka geo-engineering) – just no. In other words, Johnson’s net zero target is based on the assumption that come 2050 the ‘net tech’ will be cheap enough to employ, be scalable to meet the demand and won’t tailspin the planet’s climate once it’s put into effect. To use another metaphor from Hickel’s book: we are jumping off a cliff in the hope that we discover how to fly before we hit the ground.

But suppose carbon capture and storage (CCS) was the way forward, what then? Well, you’d expect the UK government would be throwing the kitchen sink at this new technology. Here’s how the CCC’s 2020 Progress Report to Parliament summarises the UK Government’s commitment to CCS:

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is a key pillar in achieving Net Zero, requiring significant progress in the 2020s to get on track to meeting the target by 2050. However, it is yet to be developed at scale in the UK and there was little progress in the 2010s. It must be a priority progress area for the 2020s. The Government cancelled two CCUS commercialisation programmes since 2008, halting progress in the sector…

CCC, 2020 Progress Report to Parliament, p80

The UK Government’s 10 point plan

Ok, ok, so the UK Government isn’t doing much to support CCS. But at least it has a plan, right? A 10 point ‘green’ plan? Oh, yes, that. Banning the sale of new petrol and diesel cars by 2030; £4bn funding for various emissions-cutting proposals; create 250,000 green jobs; ‘build-back’ better to deliver the net zero target we’ve talked about. It all sounds jolly marvellous.

But read the small print, as Simon Evans of CarbonBrief has done, and you’ll notice that the ‘plan’ was actually more like an ‘ambition’ that, if fulfilled, would only meet half of the UK’s 4th-5th carbon budget 2023-32 and would not get us to net zero by 2050. Furthermore, the headline figure of £12bn to finance the plan comprised of just £3bn in new money. In short, it’s a cheap ambition that would only get us half way to achieving an unfair target that would, even if possible, blow our carbon budget clean out of the water.

Putting aside the plan/ambition, take a look at what the UK Government is actually doing to retard our prospects for a green and ecologically sustainable recovery. Here’s my work-in-progress list:

- Johnson’s Chancellor Sunak announcing last year a £27bn budget over five years to expand Britain’s road network for all those fewer petrol and diesel cars we can expect from the ’10 point plan’;

- The emissions from all those fewer cars using all those new roads is going to be 100x what the Government claimed;

- Determined to expand Heathrow airport, the UK Government continued its appeal through the courts system and, in December, the Supreme Court overruled the Appeals Court, finding that the expansion was compatible with the UK’s Paris Agreement commitments;

- That coal mine in Cumbria.

- Johnson’s decision in March to allow new North sea oil and gas exploration;

- Also in March, Johnson;s decision to scrap his £1.5bn green homes grant scheme – a scheme that offered households grants of up to £5-10,000 to install insulation or low-carbon heating;

- Finally, though I’m sure there are many, many examples that I’ve missed (I haven’t even mentioned HS2!), the UK government’s utterly dumb decision to cut its aid budget, one consequence of which is that there will be a quarter less funding for education. Investment in education, particularly education for young girls and women, is one of the most effective interventions for combatting climate change.

The road back from hell

In his book Net Zero, Dieter Helm suggests we all start a carbon diary and record everything we consume that has a carbon component. It would quickly reveal, he argues, “just how unsustainable our lifestyles have become” (p.6, my emphasis). Yes, for some it’s a lifestyle choice; but for many others it’s a necessity born from inequity, exclusion and prejudice. Helm points out that the current focus is on net zero production, but the real challenge will be net zero consumption. And he argues for a carbon tax on consumption that should be applied domestically but also internationally, applied at state borders. Carbon pricing would, in theory, help diminish markets for carbon-intensive products, and encourage a reduction in consumption. That has to happen.

The reason carbon should be taxed is that polluters like you and me should pay for the costs we cause through our over-consumption. If we face up to our pollution and pay for it, we will be worse off. We will have to live within our means. That requires sustainable consumption, not polluted consumption.

Helm, Net Zero: How We Stop Causing Climate Change, 2020, p123.

Easy to say, difficult to do of course. You aren’t going to just stop consuming if you identify as a consumer – and most of us do, let’s face it. Capitalism is predicated on consumption and we are consumers; so achieving net zero consumption would certainly require more than a potentially regressive tax. And it would require a system change, a just transition, before most of us could even begin to think about keeping a carbon diary. If you live day-to-day in precarious employment, the idea of a carbon diary is, well, ridiculous. I ‘lived’ on benefits for a couple of years bringing up my kids as a single parent. I hate keeping diaries at the best of time; in the worst of times it’s never going to happen.

The Public Health Case for a Green New Deal

So something else has to happen. Medact has recently published a report presenting The Public Health Case for a Green New Deal. It’s a great report, also summarised in the BMJ last week. It has five key demands: rapidly decarbonise our economy; create well-paid, secure work and retraining for people working in high-carbon industries; combatting air pollution; ensuring quality homes for all; and securing food and land justice. Our economy is making us sick, and Medact’s report demonstrates not just the health benefits of a Green New Deal, but also the contribution that health can make to achieving a new, better economy – one that is fit for purpose:

The Health for a Green New Deal campaign shows that the health sector can play a critical role in the wider movement to build unstoppable social pressure for the Green New Deal we need. Those working in health are uniquely placed to draw attention to the health impacts of social and environmental injustice, and to explain how a Green New Deal can greatly benefit public health

Medact 2021, The Public Health Case for a Green New Deal, p11.

On the one hand there is an economic solution that needs to be implemented as a priority: internalise the costs of carbon pollution into the economy. Helm’s solution – the carbon tax – hits people in the wallet. Helm knows that, of course. But his answer is unapologetic: “voters need to be told the truth”. Ironically, Helm is not a fan of Extinction Rebellion, but that is the movements number 1 demand – tell the truth! That is categorically not what Johnson’s government is doing – quite the opposite in fact. If we knew the truth, we might begin to actually give a fuck.

On the other, there is a social solution that recognises the various inequities that plague our society and which, if left unchecked, could rock it to its core. Here’s Frans Timmermans, VP of the EU Commission:

“It’s not just an urgent matter – it’s a difficult matter. We have to transform our economy. There are huge benefits, but it’s a huge challenge. The biggest threat is the social one. If we don’t fix this, our children will be waging wars over water and food. There is no doubt in my mind”

That solution is a Green New Deal. A deal predicated on a new way of doing economics, a deal predicted on justice and a deal predicated on ecological sustainability.

We have a choice but we have to make it now.

We are consuming ourselves to death. Covid-19 has offered the possibility – a once in our lifetime opportunity – to do things differently. We don’t need to consume so much stuff; we don’t need to travel as much as we did; we can re-use and re-cycle what we used to throw away (can we please stop buying crappy clothes from Primark and start buying cheaper, quality clothes from charity shops). Our lifestyles can be different lifestyles – ones that aren’t constructed on the back of a multi-million pound advertising and marketing campaign but on principles of sustainability. Our work days can be shorter and healthier. And all of this can be done fairly, justly, with care and with kindness. That is not the way Johnson and the UK Government wants do things. But they are wrong.

Andrew