One of the worst aspects of depression is the ability to watch yourself disappear, unable to act in self-defense.

Barbra Jago, 2002

It’s World Mental Health Day on the 10th October. I’m going to write about mental health today because I can’t guarantee that I’ll be able to write about it in October. That’s because I struggle with chronic depression. If you are in the same boat as me, you will know that you are at the mercy of your emotions (or, more likely, a sudden lack of them), and so you have to write when you can. I’m not a psychiatrist or psychologist and thus don’t have the fluency of vocabulary to describe, technically, what depression is. But it may be worth reflecting on what depression means for me, personally and as an academic. This post may also have a cathartic effect.

Where to start? I guess with my breakdown, because it was quite insidious. Breakdowns are a long time coming and then, when you realise that you’re in one, it’s too late. My most recent breakdown started sometime in 2021. Hard to say when exactly, but I’d probably place it at COP 26 in Glasgow. I attended as a delegate, but hated it. I mean, I hated everything about it. I found myself unable to distinguish anything good from anything bad. You can probably detect my mood in the blogpost I wrote about it. That was when I was still able to feel.

Returning to England from Scotland, I became increasingly detached from reality. It was busy at work; I was teaching a module; there were the usual distractions of a Program Director. But I was aware that my relationship with the world was changing quite rapidly. I removed all of my friends’ contacts from WhatsApp; quit Twitter (again); stopped listening to the radio; stopped reading the news. In fact, bizarrely, the only entertainment I could tolerate was watching ZackScottGames episodes of Plants vs Zombies on Youtube! Thank you Zack! I completely stopped socialising. By Christmas 2021, I had all but given up speaking.

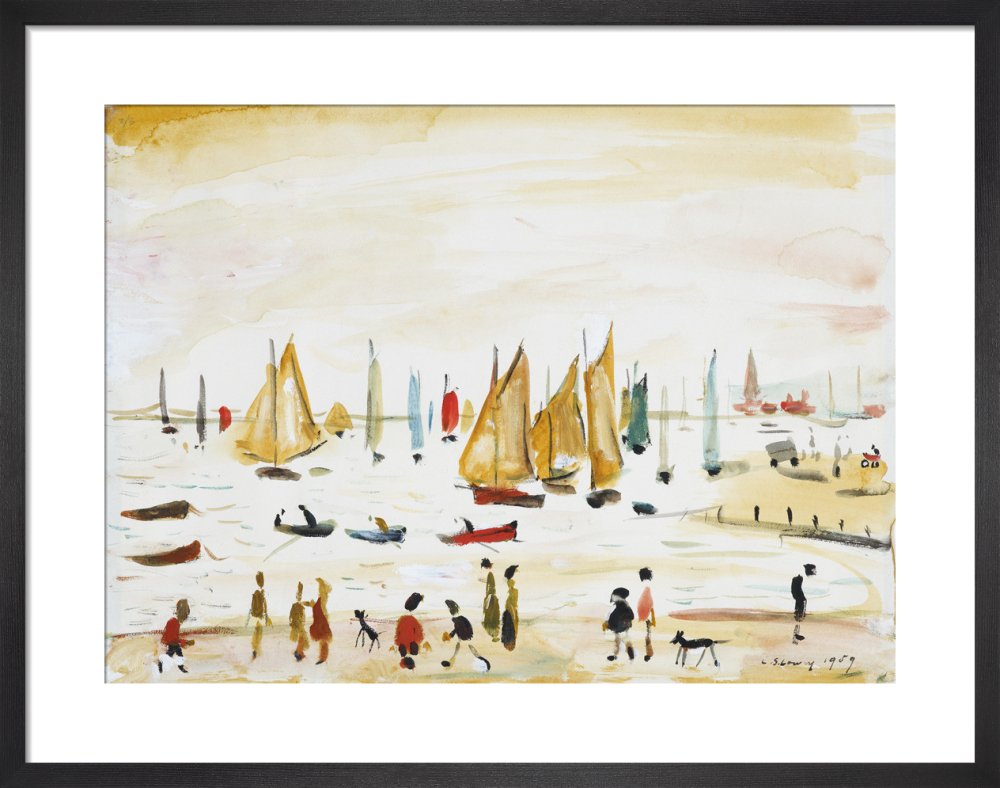

I have a copy of a painting by Lowry on my wall. By the end of January 2022, I started to see people in 2D, much like the painting. They stopped becoming 3D in my mind, probably because I couldn’t bear to look at anyone in the street. I don’t know whether Lowry suffered from depression, but he manages to paint the world I saw.

Lowry, Yachts, 1959. I’m the one in the bottom right corner.

Coming back to work in February was hard. I found it increasingly difficult to feel anything. People would ask me how I was, and I realised that I was unable to answer the question. I simply didn’t know. I didn’t feel anything about anything. Of course, that was when colleagues began to notice. If someone asks you, casually, ‘how are things?’ and you answer ‘I don’t know’, well that’s the wrong answer. If they then ask ‘are you ok?’ and you answer ‘I don’t know that either’, well you’re kind of giving yourself away. At home, alone, I remember walking into the kitchen. I just stood there, for about twenty minutes because I couldn’t reason my way into going in one direction or another. When I ventured out, I would sometimes sit down because I couldn’t think of a good reason to continue walking.

In March, a work colleague and friend asked to meet because they were worried about me. In her office, I sobbed for a while. I remember being advised to contact the University’s Advice and Counselling service – a service I have signposted so many students towards over the years. I did do that eventually; not immediately.

Depression is a ghost disability: I quite literally wanted to disappear; to become invisible. And most of the time you won’t see it in someone. That’s because they/I don’t socialise when I’m depressed. Most of the time you wouldn’t know. You are more likely to notice it by something that someone you know stops doing. Consequently, it took me a while to contact A&C, and then longer to contact a counsellor for my first appointment. I had to wait for a break in the clouds.

The university counsellor put me in touch with a local counselling service and I had regular counselling sessions this year. They are exhausting! Typically, I would have to lie on my bed for the entire afternoon following a morning session, unable to move. Mostly, the sessions were an opportunity for me to talk, or not talk. Sometimes, I would have to ‘hold on for dear life’ as my counsellor put it; often, I would just stare into space.

My depression has affected my job as an academic, and will likely continue to do so. Earlier this year, I had to cancel four speaking engagements because I couldn’t bear to hear myself speak, let alone attend a public function. Motivation is patchy, requiring considerable effort to start a project, with no guarantee that I will be able to finish it. When the depression is in remission, I make plans, reach out, start to do new things; but when it returns, I fall silent, renege on commitments, and generally disappear. It is immensely frustrating. Generally speaking I avoid conferences, and periodic bouts of self-loathing dampen most attempts at self-promotion. A few years back, I deleted my blog globalhealthpolicy.net while depressed and all the posts written on it, and I erased all my 2000+ followers on Twitter. I hope this blog doesn’t experience the same fate.

I am talking about a recent episode of depression; an intense one, admittedly. But I have looked back on my life during counselling and now realise that I have been depressed since at least my late teens. It’s easier to identify and relate to depression these days, although depression remains a taboo within society. It is still perceived to be a weakness, a sham, an excuse for not pulling your weight. And people often misinterpret my inability to engage as grumpiness or rudeness, as uncaring or anti-social. Culturally, I am in the company of a depressed donkey (Eeyore), a depressed super computer (Marvin) and ‘sadness’ in the film ‘Inside Out’. Admittedly, sadness turns out to be essential, in the end. I used to be both ‘angry’ and ‘joy’. Perhaps I will be them again one day.

It is difficult to know what to say when someone outs themselves as being depressed. If that happens to you, don’t say or do any of the following: 1. Tell that person to ‘cheer up’ or advise them that ‘tomorrow is another day’; 2. Share your own depressive moments and reassure them that ‘everyone’ gets depressed; 3. Ignore them. Allie Brosh’s comic strip How NOT To Talk To Someone With Depression is the best place to start if you want to understand depression from the perspective of someone with depression. William Styron’s Darkness Visible is also quite good.

Fortunately, I have some very supportive colleagues who noticed something was wrong, and who decided to do something about it. I don’t think that happens very often in other professions. Depression is probably quite common amongst academics. The literature tends to focus on depression amongst students. And rightly so. But it would be interesting to see some data on depression amongst academic staff.

If you’re depressed, wait for a break in the clouds, as I did, and contact a local counselling charity, if you can. Making that first step is difficult but not impossible. Helplines – such as the Samaritans in the UK (116 123) – will listen to you without judgement. If you’re unsure, here’s a guide about what to expect when you call a helpline. Your university A&C services are there for you too, so don’t feel ashamed to contact them. I haven’t been ‘cured’: I don’t socialise and I remain fearful of remission, especially as the winter approaches. But at least I now know that I can talk with someone if I need to.

Andrew

I loved, lost, and grieved deeply for the most wonderful person depression took. The frustration at not being able to help, to be rejected impacted my entire life. Depression destroys both the individual and the person who loves them.

Lowry is well known to have suffered depression, his drawings, paintings and musings are full of references to it. Artists, by their very nature are ‘on the outside looking in’ We never really fit.

Thank you for sharing your own personal experience, it has helped me more than you know.

If you have stumbled across this post, I hope you find something positive that you can take from it. I wrote it in August 2022; it’s now July 2024. By way of an afterword, perhaps I can add a few words about what happened after I wrote the post.

My depression continued and January 2023 was quite bleak. My line manager and someone I know with experience of depression encouraged me to consider medication. By the Summer, I realised I had to do something and so I went to see my GP who prescribed Sertraline. I took the drug for about 9 months, increasing the dosage 3x after consultation with my GP, and then – eventually – slowly reduced the dosage before finishing the course of the drug.

Reflecting on this, I can say that there are various routes you can take to respond to depression. In my case, counselling worked in the immediate short-term. It was necessary to remove the emotional block – like pulling a plug to empty a sink. Counselling does the plug-pulling by encouraging you to talk in a safe space. For me, it wasn’t sufficient on its own and, eventually, I had to seek a medical intervention. William Styron recounts in his account of depression (referenced in my original post) that his depression ‘simply disappeared’ on its own accord. I guess that has happened to me in the past, but it didn’t happen this time.

The effect of Sertraline was almost immediate. Perhaps a couple of days after I started taking it, the ‘voices in my head’ (I’m not exaggerating) stopped as did the internal monologue I had with them. This was immensely relieving and probably the single biggest difference it made to my life. The drug reduced all feelings of anxiety, which meant I could enter rooms and participate at meetings; I even attended a workshop and gave a presentation. I recall, with grim humour that a colleague asked me why I was so calm. I refrained from replying: ‘because I’m medicated’!

There are side effects to Sertraline, so it’s imperative you understand these and develop a good relationship with your GP. For me, it was at times quite ‘trippy’ – like you are floating. It didn’t lift my mood though, which is why I experimented (with GP advice) on increasing the dosage. It mostly numbs emotions, so you can come across as a bit vegetative at times – not always. And it is quite tiring – I had to take quite a bit of annual leave when my brain wasn’t working so well, and I was finding it hard to concentrate. I had headaches after drinking alcohol and started to take a worryingly large and regular amount of paracetamol. One final note – if you have a sex life, forget about it!

Eventually, I just felt that it was the right time to reduce my dosage and come off the drug. Initially, it felt weird – and I had one significant drop in mood where I felt very depressed and contemplated self-harm – but that was the exception. I’m off it now, and have been for a couple of months. I would say that I am in full remission and feel quite optimistic about the future.

The experience reinforces a thought that I tried to hold onto throughout these past couple of years. I kept reminding myself that I was depressed, that whatever I was feeling was not ‘real’, and that I would see and interpret everything differently in the future. It’s all too easy to lose sight of that while depressed, and you can no longer see the light at the end of the tunnel. But I promise you that the light is still there, and the negative emotions you are feeling are not ‘real’. Hold onto that thought, if you can.

Andrew