If you’ve been listening to this year’s Reith Lectures, delivered by ex-governor of the Bank of England, United Nations special envoy on climate finance and adviser to the UK Government for COP26 Dr Mark Carney, you may be feeling a tad depressed – especially if you caught his final lecture: From Climate Crisis to Real Prosperity. If you are, good, because it shows that you are alive to the reality of the climate and ecological crisis we are in. If you aren’t, you’re probably a financier.

But what you do next, however, is vital. Joanna Macy and Molly Brown’s 2014 book Coming Back to Life reviews and updates decades of training for environmental activists – work which they describe as Work That Reconnects. They describe the aim of that work thus:

“The central purpose of The Work That Reconnects is to bring people into a new relationship with their world, to empower them to take part in the Great Turning, and to reclaim their lives from corporate rule”.

Macy and Brown, Coming Back To Life. 2014, p65.

The first step in reconnecting with our world is reflecting on everything we love about it. Go ahead, pick something. Then imagine your world without it. It’s painful, right? Carney reminds us that in his lifetime – like me, he’s in his 50s (I look much younger) – the population of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians has fallen by 70%. That’s a horrific loss of life that could, and for some people does, lead to feelings of despair. But, according to Macy and Brown, we should “honour” the pain that we feel from that loss, i.e. experience it but not let it immobilise us.

Establishing a connection reminds us that we are not separate from our world; that we are not separate from one another. Carney, in the first of his lectures, refers to Aristotle’s observation that civic virtue grows with practice but atrophies otherwise. A wasting muscle, Carney calls it. Carney provides the example of “spontaneous” voluntary support for the UK’s NHS during the pandemic.

But he’s mistaken. That wasn’t an example of civic duty, it was an example of humanity. Think about it: if our civic duty does indeed atrophy through lack of expression, as Carney and Aristotle seem to think, then we wouldn’t be able to spontaneously demonstrate it. If it were a weakened muscle, it would take time to strengthen. Rather, it turns out, we were just being human; our humanity was just laying dormant, suppressed by the economic environment in which we live, but waiting to reconnect nonetheless. That’s a reassuring thought.

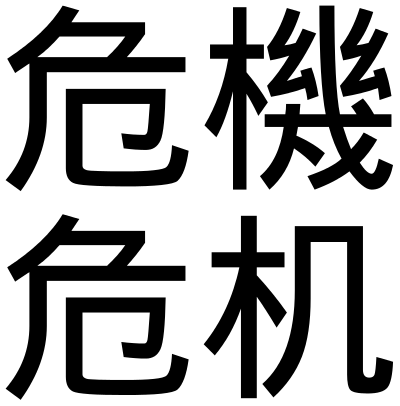

We tend to reconnect in a crisis. The Chinese word for crisis comprises two characters: one of danger, the other signifying a ‘change point’. For Macy and Brown this is important when thinking about the third stage of becoming politically active – what they call ‘seeing with new eyes’. Feeling the pain of a dying world, feeling distress, anxiety and grief is a trigger that leads to a realisation – a turning point when “we shift to a new way of seeing ourselves in relation to our world and a new way of understanding our power” (Macy and Brown, 2014, p135).

Note the interpretation of the Chinese word for crisis as the confluence of danger and a change point. Often, but incorrectly, the word is interpreted to incorporate the characters for danger and opportunity. One of the dominant themes on which Carney’s lectures rest is the description of the climate crisis as a moment of danger, but also of financial opportunity. I prefer to think of the crisis as an opportunity for change; for a genuinely different approach to politics, economics and society. Carney doesn’t, even if he says he does.

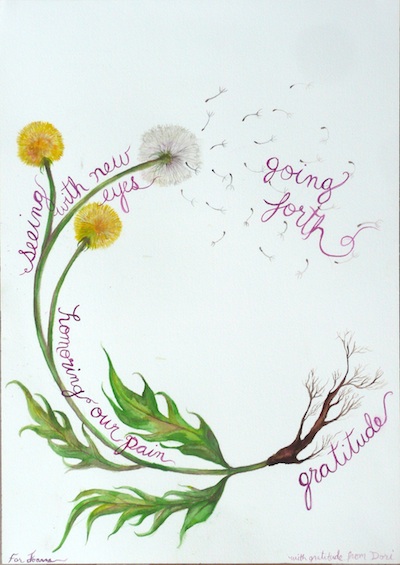

The final stage of Macy and Brown’s Coming Back To Life is what they call Going Forth. I say final stage but, actually, it’s a spiral – captured in the beautiful image below.

It’s an important stage that takes us from a passive to an active response to the climate crisis. Coming Back To Life provides numerous methods for ‘going forth’, many of which will be familiar to anyone now involved in the various climate movements that are beginning to re-mobilise. As an aside, it’s telling that Carney deliberately ignores any reference to Extinction Rebellion, preferring to acknowledge the impact that Greta Thunberg, the Fridays for Future and Sunrise Movement have had on his thinking. Not so much of an impact, it turns out.

For now, I would invite you to reflect on these words by Thunberg, and then ask yourself how much of it Carney is really – I mean really – prepared to consider.

“Until you start focusing on what needs to be done rather than what is politically possible, there is no hope. We can’t solve a crisis without treating it as a crisis. We need to keep the fossil fuels in the ground, and we need to focus on equity. And if solutions within the system are so impossible to find, maybe we should change the system itself.”

Greta Thunberg, COP24, Katowice https://www.facebook.com/dailygoalcast/videos/317250348869151/

Macy and Brown encourage us to create our own narrative for life – one that takes us beyond the ‘business as usual’ of industrial growth, through ‘the great unravelling’ – the story of ecological collapse with which Carney begins his final lecture, and towards ‘the great turning’. Macy and Brown describe the great turning in these terms:

“The Great Turning is the story we hear from those who see the Great Unravelling and don’t want it to have the last word. It involves the emergence of new and creative human responses that enable the transition form the Industrial Growth Society to a Life-Sustaining Society. The central plot is about joining together to act for the sake of life on Earth”

Coming Back To Life, p5

Carney is drifting somewhere in the great unravelling and has yet to appreciate the need to turn away from a society he has invested (literally) his entire life. In part 2 of this blog, I try to describe some of the problems with his story. We have to turn away from it.

Andrew