Andy Haines and Kristie Ebi’s review article The Imperative for Climate Action to Protect Health, published in The New England Journal of Medicine a couple of days ago, summarises the health effects of global warming now and over the remainder of this century. The authors identify three major pathways that lead from global warming to ill health: direct effects (e.g. exposure to extreme heat); effects “mediated through natural systems” (e.g. vector-borne diseases); and effects “mediated through socio-economic systems” (e.g. from increased poverty). It’s a useful analysis. But while it counsels action, the kind of action recommended to health professionals falls a long way short of what is actually required.

One of the headline statements in the review concerns what the authors regard as a “conservative estimate” by the World Health Organisation of 250,000 annual deaths between 2030 and 2050 from the effects of climate change. The authors cite the findings from a 2016 study by Springmann et al which found that reductions in food availability would result in 529,000 additional deaths between 2010 and 2050. Here’s the relevant text from the 2016 study:

Climate change reduced the number of avoided deaths by 28% (95% CI 26–33), which led to 529 000 climate-related deaths (95% CI of the relative risk distribution averaged over all climate scenarios 314 000–736 000; CC SD 105 000) compared with the reference scenario in 2050

By my reckoning, that’s an additional 13,225 additional deaths per annum added to the WHO estimate (but notice that the CI is quite wide, so it could be significantly fewer or significantly more deaths).

Even with these additional deaths factored in, the total still strikes me as conservative. In their study, Haines and Ebi refer to World Bank estimates that because of climate change 100 million people will be forced into extreme poverty by 2030. Poverty is not taken into consideration in the Springmann et al study. But less food and an increasing number of people with no money to buy whatever of the food remains? Well, expect more deaths.

Grim as these findings are, this is not the main point I want to make in this post. What concerns me about the Haines and Ebi review is the tendency of the authors to err on the side of caution themselves. Their analysis draws heavily on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special report: global warming of 1.5: summary for policymakers published last year. The report notes:

Applying a similar approach to the multi-dataset average GMST used in this report gives an assessed likely range for the date at which warming reaches 1.5 degrees of 2030 to 2052 (Ch1, p66).

Haines and Ebi, however, base regional temperature changes on the assumption that 1.5 degrees “could occur within three decades at current rates of warming” (p 265). In fact, 1.5 degrees could occur in little over one decade. Later, in relation to the impact of GHG emissions on asylum applications, the authors compare a “high-emission pathway” with an emissions pathway peaking in 2040 (p 268), the implication being that this 2040 peak is the better alternative (no, both are bad alternatives).

Although the authors make the case for the health benefits of a zero-carbon economy, there is little sense of the kind of urgent and immediate reduction in emissions required to ensure that the world does not warm beyond 1.5 degrees.

The IPCC report suggests that if we want to keep the planet within 1.5 degrees, then governments should be working towards 45% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2030, and net zero emissions by 2050 (IPCC SR1.5, Summary p14). This is the same target envisaged in the Green New Deal but much more conservative than the 2025 target demanded by Extinction Rebellion. There are a number of compelling reasons to support the 2025 target and reject the 2050 target.

For one, the planet is going to release stored heat no matter what we do (the latent heat effect). Richard Rood explains that ocean warming will eventually release an additional 0.6 degrees into the air even if we cut emissions to zero tomorrow. Why? Because “there’s a delay in air-temperature increase as the atmosphere catches up with all the heat that the Earth has accumulated”. So that takes us beyond the 1.5 degrees right there.

But we also know of a number of ‘feedback loops’ that will almost certainly interrupt the linear projections of global warming described in the IPCC report. Take the ice-albedo effect. Summers in the arctic could be ice free by mid century, and this so-called blue-ocean event could itself hasten a latent-heat ‘tipping point’. The dark ocean will absorb more heat than the white reflective ice, and with no ice to absorb the energy from a warming ocean, the arctic will heat up even more, threatening to release seafloor methane and further alter the jet streams.

Quantifying the additional warming from these feedback loops is difficult and estimates incorporate wide intervals. The IPCC 1.5 report does not factor these loops into its warming projections for precisely that reason. Nevertheless, scientists have attempted to put a number on the effect. Schefer, Brovkin and Cox’s 2006 study, for example, estimated that feedbacks would promote warming from anywhere between 15-78% on a century scale. So, between 0.2 and 1.15 degrees of additional warming. Add that to the 0.6 degrees Rood talks about, and we’re rapidly approaching 2 degrees!

The point is this: the sooner we achieve net zero emissions, the better! We simply do not know when feedback loops will kick-in, so setting a target of 2050 knowing that emissions estimates do not take into account likely, rapid, disruptions to the CO2 pathway, strikes me as plain irresponsible. And remember, the odds the IPCC gives us are not great: the 2050 target only gives us a 50:50 chance of keeping below 1.5. For a 66% chance, you’re looking at 2040, and if you want much better odds – say 90% – then you’re looking at the 2020s.

Finally, and this will be familiar to many, the IPCC recognises that the chances of keeping within 1.5 degrees without having to sequester (aka ‘suck’) carbon back out of the atmosphere are slim-to-the-point-of-impossible:

As almost no cases have been identified that keep gross CO2 emissions within the remaining carbon budget for a one-in-two chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C, and based on current understanding of the geophysical response and its uncertainties, the available evidence indicates that avoiding overshoot of 1.5°C will require some type of CDR in a broad sense (IPCC SR1.5 Ch2, p114).

But the technology required to do that, namely BECCS or bio-energy with carbon capture and storage, has yet to be proven at scale. Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is risky. Here’s what the IPCC has to say about it:

CDR deployed at scale is unproven, and reliance on such technology is a major risk in the ability to limit warming to 1.5°C. (SR1.5 Ch2, p96)

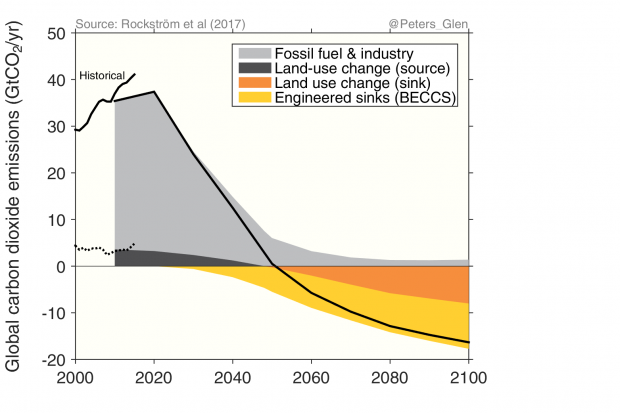

So if we want to avoid having to resort to it, we have to bring the target date for zero emissions forward – to around 2026 according to Glen Peters (see image below).

It should also go without saying (because the IPCC report warns us) that the longer we leave it before we achieve zero emissions, the steeper the remaining emissions curve. Indeed, every year of delay shaves two years off the time we have to meet our target (i.e. do nothing in 2019, then the target becomes 2048; do nothing in 2020 either, and the target becomes 2046, etc.).

So what to do? Haines and Ebi bring action back to health professionals thus:

Health professionals have leading roles to play in addressing climate change. They can support health systems in developing effective adaptation to reduce the health risks of climate change, promote healthy behaviors and policies with low environmental impact, support intersectoral action to reduce the environmental footprint of society in general and the health care system specifically, and undertake research and education on climate change and health. The pervasive threats to health posed by climate change demand decisive actions from health professionals and governments to protect the health of current and future generations.

Sure, you can do all that AND NOTHING WILL CHANGE! We are at a moment in time where decisive action means – quite literally – taking to the streets. It’s very difficult to understand this if you are over the age of 15, but it is necessary. In order to avert impending catastrophe, and I don’t use that word lightly, governments must be shaken physically out of their stupor. This is the job of health professionals as much as it is the job of schoolchildren. At the moment, nationally determined commitments of governments commit to 3-4 degrees of warming, and those commitments won’t be reviewed until 2020 or come into effect until 2030. Can you hear the can being kicked down the street?

We must try to bring the target date for zero emissions as far forward from 2050 as possible – to the 2020s and 2025 if possible. But to do that, we have to join the movement emerging from under us. On April 15th and for two weeks from that date, Extinction Rebellion is planning a massive mobilisation in London and globally. If you are a health professional, then I hope to see you there. For me, I see it as our best, last chance.

Andrew

I don’t mind admitting that climate science is not my professional field. That means that I am learning as I go. The language is unfamiliar, the interpretation of data difficult, and the concepts are often baffling. Consequently, if you are a climate scientist, reading this post may be like listening to someone play the violin for the first time. So bear with me! If there are errors, point them out; help me learn!