COP26 is taking place in Glasgow from 31st October to the 12th November. The UK government, which is co-hosting the event with Italy, has produced an explainer – read it carefully because, as COP 26 President-designate Alok Sharma ‘underscores’: “Climate change ultimately threatens life on Earth”. The explainer describes four broad aims to this year’s COP: 1) Secure global net zero by mid-century and keep 1.5 degrees within reach; 2) Adapt to protect communities and natural habitats; 3) Mobilise finance; and 4) Work together to deliver. As we roll – or cycle in my case – towards the COP (I’m cycling to Glasgow from Shrewsbury), here are some initial thoughts about these aims.

Aim 1: Enter emergency mode

I’ve written about the net zero by 2050 target date before. There’s no scientific basis for that date. It’s only 2050 because that’s a numerically aesthetically pleasing number. Furthermore, we’re beginning to hear an increasing number of scientists saying publicly words to the effect of ‘this [insert climate change effect] took us by surprise/wasn’t captured in/predicted by the models/is happening more frequently/intensely/quicker than we thought it would’. Aaron Thierry has started to compile a list of examples of these declarations. Sure, when you start looking for examples of something, you generally find lots of examples of that thing. But, when you put them together like Thierry has done, it starts to become really unsettling.

In the light of his Twitter thread, Thierry asks a couple of very important questions: “Have scientists been systematically underestimating the impacts? And if so how should we as science communicators convey this to the public & policy makers?” Peter Kalmus‘ answer is ‘be blunt’! “To lower the odds of civilizational collapse” he argues “society must shift into emergency mode”. The net zero by 2050 target is not being in ’emergency mode’. Politically-speaking, we are not in a ‘state of emergency’; climatically and ecologically speaking, we most definitely are.

The ‘net’ part of net zero is also becoming increasingly worrying. I’ve written about this too – the fantasy that technological developments will allow us to meet our 1.5C target by drawing down carbon from the sky and doing something sustainable with it. Kalmus’ Guardian article talks about the folly of this approach, and you can read about its limitations here, here and here. Here’s how Kalmus describes progress thus far:

The world’s largest direct air capture facility opened this month in Iceland; if it works, it will capture one ten-millionth of humanity’s current emissions, and due to its expense it is not yet scalable. It is the deepest of moral failures to casually saddle today’s young people with a critical task that may prove unfeasible by orders of magnitude – and expecting them to somehow accomplish this amid worsening heatwaves, fires, storms and floods that will pummel financial, insurance, infrastructure, water, food, health and political systems.

Peter Kalmus, Guardian, 10/09/21, ‘Forget plans to lower emissions by 2050 – this is deadly procrastination’

As Greta Thunberg tweeted, this is “a somewhat sobering reality check when it comes to the technology we seem to trust with our lives”. And yet, it seems increasingly apparent that this is what we are pinning our hopes of limiting global warming to 1.5C. But not in the way you might imagine. It seems unlikely now that we will avert a global increase of 1.5C of warming (note that the median is already 2.0C over land – the lower ocean surface temperature brings the global median down to 1.1C) at some point in the next two decades. The best we can aim for is most likely an overshoot and, thanks to technology yet to be developed at anywhere near the scale required, rapid carbon drawdown to bring the warming back to 1.5C. To return to the wording of the first COP26 aim, this is what ‘keeping 1.5 degrees within reach’ means. It’s like that move in the action films where the hero runs off the cliff and, miraculously, arches back and just manages to hold onto a piece of the rock face, pulling herself to safety. That happens in the movies; the question is whether you want to bet on it happening in reality.

Oh, by the way, were you reading the COP 26 Explainer carefully? Were you? Did you see what Alok did in the quote I gave you at the top of the page? Here it is again: “Climate change ultimately threatens life on Earth”. It’s the word “ultimately” that’s important. It suggests, doesn’t it, that whatever is going to happen is going to happen ‘at some point in the future’? In fact, climate change is not just threatening but actually ending life right now. Ten years ago, Peter Raven and colleagues made an astonishing/terrifying prediction:

“Biodiversity is diminishing at a rate even faster than the last mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous Period, 65 million years ago, with possibly two-thirds of existing terrestrial species likely to become extinct by the end of this century.”

Raven et al 2011, Introduction to special issue on biodiversity.

A few years later, Philip Cafaro referred to the loss of life as ‘a mass extinction event’ (the sixth in the Earth’s history), identifying climate change as one of five direct drivers (habitat loss, the impacts of alien species, over-exploitation, pollution, and climate change) which in turn are driven by increases in human population and increases in economic activity. Here’s how he describes the latter two drivers:

“The forces driving extinction are increasing as individuals pursue wealth, corporations pursue profit, governments pursue economic and demographic growth, and ever more people consume, degrade, and appropriate ever more resources”.

Cafaro, 2011 , Three ways to think about the sixth mass extinction

It is no coincidence that our climate and biodiversity crises are concurrent. The IPBES/IPCC co-sponsored workshop report on biodiversity and climate change explains the synergies between them very clearly, noting almost in passing that human modifications to land and sea “are associated with the loss of 83% of wild mammal biomass, and half that of plants” (p14). That loss (equating to 1 million species now facing extinction) is detailed in IPBES’ Global Assessment Report (you can read the SPM here).

This is happening now but the language we are using to describe that reality is not the language we need to be using to describe our plight. We have to tell it like it is, regardless of how unsettling or frightening that may be. This is no time for a Conservative to be conservative in their choice of phrase.

Aim 2: Adaptation program? What adaptation program?

What about the second broad aim of COP26 – adapting to protect communities and natural habitats? There was a lot of discussion in June this year with the publication of the UK’s Climate Change Committee Progress Report to Parliament: Progress in adapting to climate change. Here is the CCC’s rather concerning conclusion:

The UK does not yet have a vision for successful adaptation to climate change, nor measurable targets to assess progress. Not one of the 34 priority areas assessed in this year’s progress report on adaptation is yet demonstrating strong progress in adapting to climate risk. Policies are being developed without sufficient recognition of the need to adapt to the changing climate. This undermines their goals, locks in climate risks, and stores up costs for the future.

CCC, 2021 p.10

Well, that’s a damning assessment! Especially so when you consider that by mid-century UK winters will be warmer (by 1C) and wetter (+5%), summers will be hotter (by at least 1.5C) and drier (and when it does rain, it will be more intense and thus increase risks of flooding), and sea level will rise 30-40cm. The CCC warns that despite stronger national climate commitments “global warming of up to 4ºC above pre-industrial levels by 2100 cannot yet be ruled out” (p17).

Nevertheless, the CCC found adaptation planning inadequate in 27 of 34 priority areas. The UK has produced a National Flood Strategy and is adapting key infrastructure sectors (flood and water management, road, rail, and energy sectors). But risk management of supply chain interruptions, ports and protection of biodiversity in freshwater habitats has declined.

According to the CCC, the UK government basically needs to get its adaptation act together. Amongst many other things described in detail in the CCC’s report, here are some key recommendations:

- In terms of the natural environment, the Government needs to set outcome-based, long-term targets for widespread habitat restoration;

- In terms of infrastructure, it needs to focus on reducing the vulnerability of the power system;

- In terms of health and the built environment, houses are still not resilient to heat, water efficiency or flooding (surface water) – and they need to be;

- In terms of business, supply chains for food and medical supplies, and also further progress required on the Government’s ‘green recovery’ (I’ve critiqued this so-called green recovery elsewhere), but putting all of that to one side for a moment, the CCC notes that Johnson’s ‘Ten Point Plan’ is all about reaching net zero and nothing about adaptation;

- In terms of support for businesses, it’s unfortunate that the UK Climate Impact Programme closed in 2016, leaving a gap in support for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). And, of course, local government need to be properly funded;

- In terms of risk to the UK from climate change overseas – there is nothing in the UK Government’s National Adaptation Programme on this. The UK Climate Change Risk Assessment 3 provides details of the specific risks (food availability, international supply chains, public health) and systemic risks from multiple impacts that will “cascade across the globe”. The UK needs to assess climate risks in future trade deals; dietary changes; look at food supply chains (just-in-time is not working); monitor emerging disease pathways; plan for increased unpredictability;

- In terms of metrics, the UK Gov needs to provide clarity on frameworks for monitoring species abundance, indicators for flooding, improved surveillance of disease vectors and vulnerability measures for infrastructure;

- The 3rd National Adaptation Programme must be “more ambitious, more comprehensive and better focused on implementation” (p26)

Aim 3: Mobilising finance, but for what?

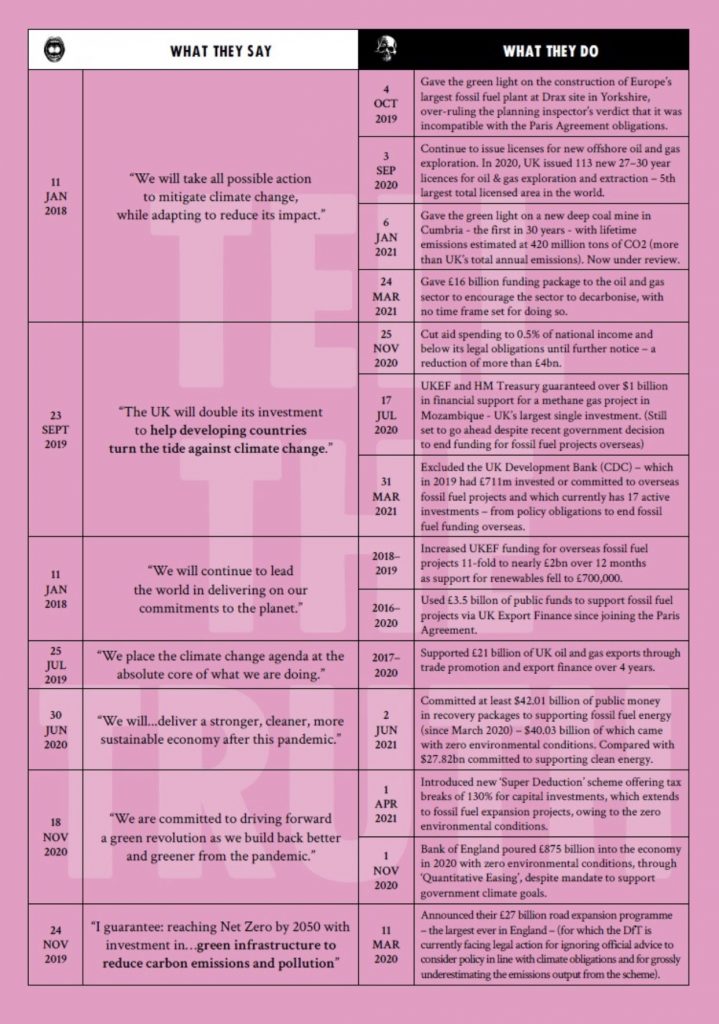

The UK Government announced way back in 2019 (anyone still remember 2019?) that it would double its climate change spend to £11.6 billion over a five year period from 2021/22 to 2025/26. Ok, so that’s great. But as we all know, it then decided to cut its international aid budget to 0.5% of GNI and voted in July to keep it cut. So that’s not so great – at £10bn, it’s the lowest for ten years and £4.5bn lower than last year. Compare that to the £372bn the Government is expecting to spend on Covid-19 measures or… well, take a look at this handy table produced by Extinction Rebellion:

The text is a bit blurry, but can you see the £16 billion figure (fourth row down in the ‘what they do’ column). What’s all that about? In March this year the UK government announced it would be supporting continued fossil fuel extraction (FFE) in the North Sea. The fact that it is supporting FFE is deliberately obscured in the Press Release.The £16 billion is being given on the promise from the fossil fuel industry that it will reduce its emissions by 50% by 2030. Ever since the brothers Meinshausen gave us the concept of the global carbon budget, we’ve understood that most fossil fuel is unburnable – i.e. it must stay in the ground. In a paper published in Nature last week, we now know exactly how much of it must stay buried. Here’s the main result of the analysis:

By 2050, we find that nearly 60 per cent of oil and fossil methane gas, and 90 per cent of coal must remain unextracted to keep within a 1.5 °C carbon budget.

Welsby, 2021 Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5 °C world

Furthermore, the authors of the Nature paper “estimate that oil and gas production must decline globally by 3 per cent each year until 2050”. That’s not what is going to happen in the North Sea, however. According to Friends of the Earth, “the UK’s 5.7 billion barrels of oil and gas in already-operating oil and gas fields will exceed the UK’s share in relation to Paris climate goals – whereas industry and government aim to extract 20 billion barrels”. Actions, it seems, speak louder than words.

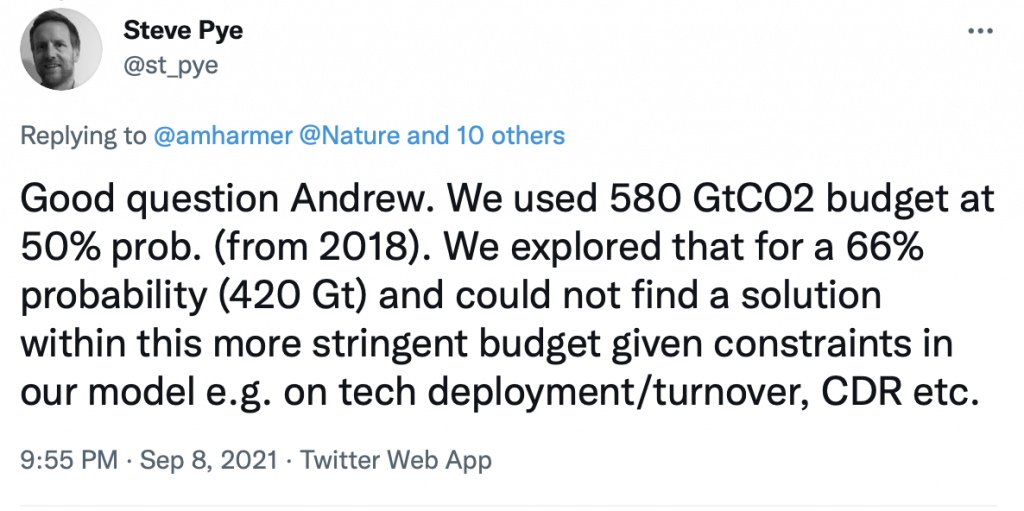

It’s important to understand that Welsby et al’s analysis is based on a target of keeping global warming to 1.5C at 50/50 odds. I asked the authors why they weren’t more ambitious. One of the authors, Steve Pye, replied:

The point I’m trying to make is that the UK Government is mobilising finance, just not for the right things. Continuing to financially support FFI, even if that support is spun as encouraging the Industry to wean itself off fossil fuel (which it isn’t), is the wrong thing to do. Or, if you prefer, “a colossal failure in climate leadership in the year of Cop26” (Mel Evans, head of Greenpeace UK’s oil campaign). What the Government should be doing instead is setting clear targets for the phase-out of UK old and gas extraction not providing FFI huge sums of money to continue extracting on a promise of something at some time in the future.

Aim 4: In bed with the enemy

I cut my academic teeth studying global health partnerships, so I know what ‘working together to deliver’ means in practice – it’s code for working with the private sector. There is no doubt that the elephant in the room is the Fossil Fuel Industry. If they ever re-make the film ‘Thank you for smoking‘, the producer will have to re-shoot the classic ‘Restaurant Scene‘ (where representatives from the alcohol, arms and tobacco industries argue about which of them is responsible for the most daily deaths) to include a representative from the FFI. I’ve written about conservative climate change mortality estimates previously, and it’s high time we had an accurate re-assessment of.this vital statistic, be more explicit about linking mortality and morbidity directly to fossil fuel companies, and hold them to account through the legal system. Not to mince my words, the FFI is not our ‘partner’, it is a cancer. So when you hear government saying that ‘we’ have to ‘work together’, the correct response is to ask: who is ‘we’?

Thanks to a study from DeSmog, reported in The Guardian last week, we now know that UK ministers met with FF and biomass industry leaders nine times more than with clean energy producers. Between the 22nd July 2019 and 18th March 2021, BEIS met 63 times privately with FFI/BI representatives. This degree of access provides an opportunity for FFI lobbyists to shape government policy so that it reflects FFI interests. One might reflect on the third aim above, and ask whether continued oil and gas extraction in the North Sea is an example of what lobbyists can achieve given sufficient contact with ministers?

Let’s just return to the CCC report discussed above. One of its recommendations is that the UK assess future international trade agreements in terms of climate change. Fine, super, but what is the UK Government actually doing? As scooped by Sky News last week, and reported widely in the British media, the UK-Australia free trade agreement (FTA) removed specific references to the temperature goals of The Paris Agreement. As far as the two countries’ trade ministers are concerned, this FTA is an example of aim 4 of COP 26 where “Australia and the UK have agreed to work cooperatively on environmental issues, including emissions reduction” (AU trade minister Dan Tehan, quoted in the Guardian article linked above). It’s hard not to interpret this omission in UK-AU trade relations as being inconsistent with either country’s climate commitments.

Before closing, I just wanted to mention the work that Global Justice Now (GJN) has been doing in relation to the extent that so-called ‘corporate courts’ can threaten the climate. GJN’s March 21 campaign briefing explains that ‘corporate courts’ are tribunals that convene privately to hear disputes between states and investors that have signed trade agreements. There are an increasing number of bilateral trade agreements (BTA), and many include Investor-State Dispute Settlements (ISDS) that both states agree to honour. Within the BTA, the ISDS protects investors against any subsequent decision by either state party that impacts negatively on the investor’s financial interests – it could be a decision to ban toxic chemicals, introduce a sugary drinks tax, anti-smoking policies, capping water rates, or simply raising the minimum wage. Increasingly, however, multi-national corporations are pursuing ISDSs through ‘corporate courts’ to seek compensation for states that attempt to introduce climate policy. For example, coal company RWE sued Netherlands €1.4 billion for deciding to phase out coal to generate electricity by 2030; UK fracking company Ascent Resources sued Slovenia for seeking to protect its groundwater from pollution from fracking; and UK oil company Rockhopper has recently sued Italy for banning offshore oil drilling. There are many examples of such ISDSs and they run counter to the broad aim of ‘working together’ internationally to reduce the impact of climate change.

So where does that leave us? It’s essential that we don’t take these broad aims as ‘given’. They are highly contested aims even if, on paper, they sound quite reasonable. The ‘net’ of net zero is extremely problematic, and the 2050 deadline is too late. We must shift into emergency mode and, to quote Thunberg, start treating this crisis as a crisis. We should not lose sight of the importance of mitigation but, at the same time, start taking adaptation seriously. The UK government currently has no measurable, time-bound plan. A response to a crisis of this magnitude needs financing at sufficient scale. £11.6 billion is – frankly – peanuts. And, finally, there are enemies in this story. The FFI has, throughout its history, distracted, lied and denied, threatened and murdered its way to profit at the expense of all else. Its actions are killing us and everything we love. It has no place at the table.

Andrew