I like to think that people reading my posts come away from the experience in awe of the world around them but, mostly, of my creative genius. However, I also recognise that one or both of my readers may also be feeling a bit like this at the thought of reading yet another post on WHO’s FRIGGING EXECUTIVE BOARD MEETING. I mean, really, enough already. Ok, ok, OK! This one will be the last, I promise, and it’ll be short (it so won’t). Below, I write about EB154/26 Economics and health for all: Report by the Director General, which builds off The WHO Council on the Economics of Health for All’s Final Report Health for All: Transforming economies to deliver what matters. The bottom line – the narrative is not especially new and it seems to be deliberately ignoring important parts of the story.

I’ll start with the Council’s Final report. Given that the ten Council Members include some of the finest economists in the world (Mazzucato, Raworth and Ghosh, for example), it seems a bit (a lot) absurd for someone who knows very little about economics (me) to be even writing about this report. Maybe I should just leave it there….Nah.

Might as well begin with the Preface, written by Mazzucato in her capacity as Chair. It contains some powerful statements. Here’s part of it:

A healthy population is not just human and social capital, or a by-product of economic growth. Health is a fundamental human right. Alongside a healthy and sustainable environment, human health and wellbeing must be the ultimate goal of economic activity. This goal requires investment and innovation by all actors in the economy, which can also help steer the rate and direction of economic growth. Growth not for growth’s sake but for people and planet.

What’s not to like there? But that final phrase “growth not for growth’s sake” – it sounds like a critique of capitalism, doesn’t it? Consider the opposite: growth for growth’s sake. That sounds like the blind logic of capitalism to me. Marx described one of the imperatives of capital expansion thus: “the development of capitalist production makes it constantly necessary to keep increasing the amount of the capital…in a given industrial undertaking, and competition makes the immanent laws of capitalist production to be felt by each individual capitalist, as external coercive laws” (Marx, Capital p649 quoted in Dowd Capitalism and its Economics (p6). I am all for an economy that is there for people and planet, so it’s great to see this expressed so bluntly right at the start of the Council’s report. But let’s be clear, capitalism is not there for people and planet – it is a system unto its own. It also persists because a small number of people can benefit hugely from it. So, if you don’t want growth for growth’s sake, you will – at some point – have to contend with capitalism.

I’m 100% behind the ‘ultimate goal’ of “a healthy and sustainable environment, human health and wellbeing”. But let’s also be clear, some actors in the economy are not. They just aren’t. They only care about themselves and the return that their companies make for their shareholders. There is a huge literature demonstrating this but you could do worse by starting with Provost and Kennard’s new book Silent Coup. So, I’m really not convinced that the call for “investment and innovation by all actors” is going to achieve the goal – it just seems wildly inadequate. If you want all the things expressed in the goal, you will – at some point – have to contend with those actors who don’t want to play ball. And they are very powerful.

The Executive Board document summarises the work of the Council thus:

During the Council’s two-year term, its reports focused on identifying ways to put the principle of health for all at the centre of government decision-making and private-sector collaboration at the national, regional and international levels.

I don’t know whether I’ve imagined the last 30 years of my life or not, but for all of that time (I’m going to go out on a limb here) I would say that ‘private sector collaboration’ has been a disaster for peoples’ health. There are many, many, MANY examples to support this argument – of huge profits going hand-in-hand with low-quality services, of services that were once free becoming expensive or just no longer being supported, of lobbyists bending their wills towards weak and/or greedy politicians in order to influence policy for the benefit of their private clients, of a revolving door between public servants and private interests, etc. I could go on but you get the point. See this Oxfam report for just one example – corporate hospitals. Part of the reason for this is power, a big part is ideology, and underlying it all is the imperative noted above – growth for growth’s sake. So, I’m afraid that my heart sank when I read the EB Report. It’s like none of the last three decades happened and we’re coming to the problem anew.

The Council Report is – in parts – inspiring, and you can really hear the voices of some of the authors speaking through it – the need to “reshape” the economy (Raworth); governments rethinking value (Mazzucato); the impact on health of austerity or debt (Ghosh). But I’m not sure what to make of bold statements like: “The ultimate outcome must be that every person should be able to flourish physically, mentally and emotionally”. I mean, I agree of course – who wouldn’t want that outcome? It’s just that ideology dictates how that flourishing can best be achieved: Liberalism would focus on the individual; Socialism on society; Conservatism on tradition and ‘paternal’ support; and Neoliberalism on economic liberty via markets. And yet, ideology is so conspicuous by its absence in both the Council’s report and the EB document that it feels like a deliberate omission. Most global health courses will introduce its students to ideology (mine do) – you can’t understand the social, economic, political or commercial determinants of health without understanding ideology. So, just ignoring it in these reports is very odd.

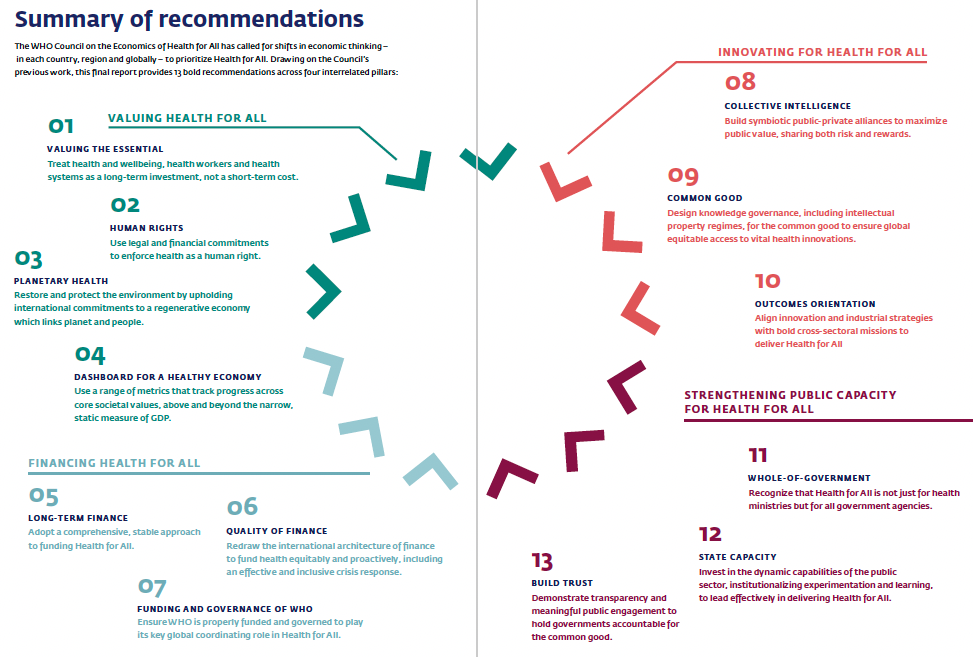

The list of 13 recommendations in the Council’s report make for an upbeat read. It’s genuinely refreshing to read here many of the arguments made elsewhere by the authors.

To return to the two main points above – capitalism and ideology – the report does address both issues indirectly. As is well known, Raworth studiously refuses to refer to capitalism explicitly, seeing it as a polarising concept (which it is, of course: some do but most don’t own the means of production – but that’s not what Raworth means). So, the critique comes obliquely via various routes as “conventional economic theory” is put under the authors’ critical lens. For example, the report argues for “mission-driven governments that work with purpose-oriented businesses and civil society to deliver on people-oriented outcomes” (“purpose-oriented businesses” are those that “maximise stakeholder rather than shareholder value”). Ok, that would be great – unless you were a shareholder – but how would this be achieved?

One argument is that “Governments must rethink value and reshape and redirect the economy, guided by new metrics”. Out with GDP and in with the “Doughnut model” or Genuine Progress Indicator. The Wellbeing Alliance is presented as an example of how that rethinking might be put into practice. It’s a “movement of movements” whose work aligns with many of the reforms argued for in the report. In addition to missions and purpose-reorientation, there are recommendations to stump up more money to deliver Health for All; ensure a “properly resourced WHO; “replace counter-productive austerity” and suspend debt repayments; and support for The Pandemic Fund. “Collective intelligence” is also a term introduced and described in the report as a way to describe the perennial call for the public and private sectors to come together and ‘share’ their collective wisdom.

The authors are not blind to the problems: “Too often, these relationships tend to be parasitic, with large amounts of public funding flowing to private sector actors without conditions attached to align this funding with the public interest”. So, they call for conditions to be attached to public funding; ask us to consider health technologies as part of “a global health commons”; view patents from “a knowledge governance” rather than a “generating revenue” perspective; and stop thinking of innovation as something that is led by markets. At the route of the recommendations is this line (presumably from Mazzucato): “It is crucial to re-invest in the ability of governments to drive transformative change”. That, in turn, “necessitates meaningful public engagement and accountability to build trust”.

Again, some of these recommendations are ones that many would and could support. But the broader arguments have been percolating for decades, perhaps centuries, and (unlike the Council’s report) expressed in ways that do bring ideology – neoliberal ideology in particular – to the front of the analysis. For example, The Struggle for Health – a pamphlet written by Amit Sengupta, Chiara Bodini, and Sebastian Franco – pulls no punches in its preface: “Neoliberalism, the dominant economic system in the world today, with its principal objective of endless accumulation of capital and the creation of profits for a tiny elite, stands in contradiction to the rights of populations to health and health care”. I recommend reading this pamphlet: it covers many of the same issues and shares some similar concepts to the Council report, but it is explicitly anti-capitalist, situates health within the context of struggle and is more socially-oriented than the member-state oriented narrative of the Council report.

Sadly, though, I wonder if time is running out? It’s no coincidence that one of the key themes of the World Economic Forum in Davos this year is Rebuilding Trust – another perennial political topic but one that is becoming increasingly urgent to address, particularly if we want to avoid the slow (possibly quick) descent into autocracy. Here is the final recommendation in the report: “In addition to building their capacity to work in the public interest, governments need to build public trust that they are doing so”. Again, am I living in an alternate reality? Governments have had a spectacularly bad time of it recently, eroding trust to the point where dictatorship actually seems preferable over democracy to a sizeable percentage of the population. Multi and trans-national corporations on the other hand are doing splendidly – with 148 corporations garnering $1.8tn in total net profits in the year to June 2023, a 52% jump compared with average net profits in 2018-21. So, YES, governments need to restore trust – OBVIOUSLY they need to do that. But they aren’t doing that. Instead, many senior level politicians continue to enrich themselves over and over again through the position of their political office. The “collective intelligence” is limited, it seems, only to those who would profit from it, be it friends of friends of politicians or the corporations.

The Council report and the EB summary document focus on economics, but the recommendations are political in nature. To me it feels like the end game – a phrase the marvel universe has depressingly brought into public discourse. 2024 continues with multiple crises that demonstrate how governments under the leadership of brutal men can cause carnage. The year may culminate with a Trump presidency with all the chaos that that would bring. But 2024 also seems to be the year when many people seem to have had enough of politics generally. Of course, it is only my privileged, Western gaze that makes all this seem new and pressing – elsewhere, shitty government leaders have been fucking everything up for their people for years – aided and abetted for decades by our shitty government leaders. So all of this is not new – not new at all. It’s just a bit closer to home. I guess the point is that for the economics to change, the politics has to change first.

Andrew

Also read this excellent Commentary on EB154/26 by PHM on its Tracker website

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1TNFC31M_11XJpQWNRUOHPVskYOSaqT10-aGxk-5Vqoc/edit#heading=h.mp17nknfeq3s