The UK Climate Change Committee (CCC) recently published its report Net Zero: The UK’s Contribution to Stopping Global Warming. If you’ve never heard of the CCC, it was established under the 2008 Climate Change Act “to advise the UK Government and Devolved Administrations on emissions targets and report to Parliament on progress made in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and preparing for climate change”. As with all reports of this scale, the amount of work that has gone into writing it is considerable, and credit is due to the report’s lead authors Chris Stark and Mike Thompson. It’s also an important report: whenever you hear politicians or advocates talking about the UK’s commitment to climate breakdown, you can be sure that it is the arguments and data presented in this report that inform what they say. As the title of this post suggests, the report is best known for one number – 2050 – the date by which the UK is now legally obliged to reduce its carbon emissions to net zero. However, as I argue in this post, there is no scientific basis for 2050 to be the target date. Furthermore, and more importantly, 2050 is too late. If we continue to focus on that mid-century target, whoever writes the epitaph of our species will inscribe that date on our tombstone.

The Climate Change Committee’s 2050 target

The CCC report has a number of aims but chief amongst them (indeed, “the key question”) is to identify when the UK must reach net zero. We get straight to the point with the very first sentence: “The UK should set and vigorously pursue an ambitious target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) to ‘net-zero’ by 2050, ending the UK’s contribution to global warming within 30 years”. And lest there be any doubt, 2050 represents “the UK’s highest possible ambition” (emboldened in the original).

As you read, you may – as I did – begin to detect a pattern. Here’s an early example, taken from the Executive Summary: “The Committee does not currently consider it credible (my emphasis – I’m helping you out here) to aim to reach net-zero emissions earlier than 2050″. Later, “the UK should achieve net-zero GHG emissions by 2050…the earliest to be credibly (still helping) deliverable”. After that, well, it’s a case of live, die, repeat: “for most sectors 2050 currently appears to be the earliest credible date” (p21); “Setting a legal target to reach net-zero GHG emissions significantly before 2050 does not currently appear credible” (p21); “To continue being a credible leader, the UK should set a net-zero GHG target by 2050” (p113); “Achieving net-zero emissions domestically prior to 2050 does not currently appear credible for the UK” (p137); etc. You get my point.

So, presumably, there is some evidence offered in the report to support the “credible” date of 2050, rather than 2047, 2039, 2030 or even – as Extinction Rebellion is proposing – 2025? On a first reading, it looks as though the choice of date is based on a cost-benefit analysis. Take a look at this justification from Ch7 of the report:

“A mid-century date provides a good balance between starting early with a clear target, which may deliver lower costs (investing in low-carbon technologies and approaches now gives more scope for cost reductions from learning-by-doing), while still allowing time for high-carbon capital stock turnover without extensive early write-offs”.

CCC 2019, Ch7 p214

However, the focus of the cost-benefit analysis is not the 2050 date, which was already established in the UK’s 2003 Energy White Paper and later the 2008 Climate Act, but the net zero target. It is this latter target that the Advisory Group was tasked with reviewing (see Box 7.1) not the year by which zero emissions should be reached. Thanks to the falling cost of technology, net zero emissions by 2050 represent the same % of UK GDP (1-2%) in 2019 as the 80% emissions target back in 2008. What I suspect, therefore, is that the 2050 date was never in doubt or even in question. It is simply “a good balance”, apparently (although why and for whom is not explored any further in the report).

At the end of the report, in the Recommendations chapter, there is one last-ditch attempt to justify the 2050 target: because “it corresponds with the latest climate science” (p259). Let’s have a closer look at that claim.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2050 target

The year 2050 features heavily in both the IPCC Annual and Special Reports (AR/SR). It is mentioned 31 times in SR15’s Summary for Policymakers, for example. It also has a long history – 2050 appears as a mid-century marker in the IPCC’s first AR, back in 1990. But, and here’s the important point, 2050 has no scientific significance beyond the fact that it is a midway point between the start and the end of a century.

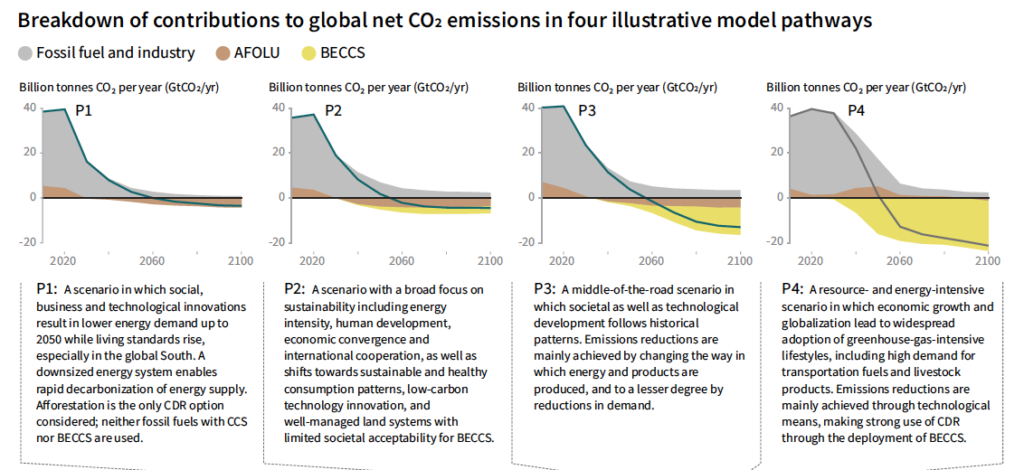

There is a widespread misinterpretation by politicians, either deliberately or through ignorance, of the science presented in the IPCC reports. The misinterpretation is that the science tells us that 2050 is the only target and, furthermore, that it is the only credible or feasible target for achieving zero emissions. I suppose this misinterpretation is understandable. Have a look at this iconic set of four pathways – the ‘shoes’, as I like to call them:

These four shoes illustrate “pathways limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees with no or limited overshoot as well as pathways with a higher overshoot. CO2 emissions are reduced to net zero globally around 2050”. This is the science to which the CCC report refers. It’s supported by headline statements such as: “In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5°C, global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030…reaching net zero around 2050”. Never mind that only 9 out of 90 model pathways reviewed allowed for this eventuality, and that 0 pathways allowed for this eventuality at better than two thirds odds. When a policymaker reads hasty statements such as “limiting warming to 1.5°C implies reaching net zero CO2 emissions globally around 2050 (high confidence)” inevitably they will take that as definitive.

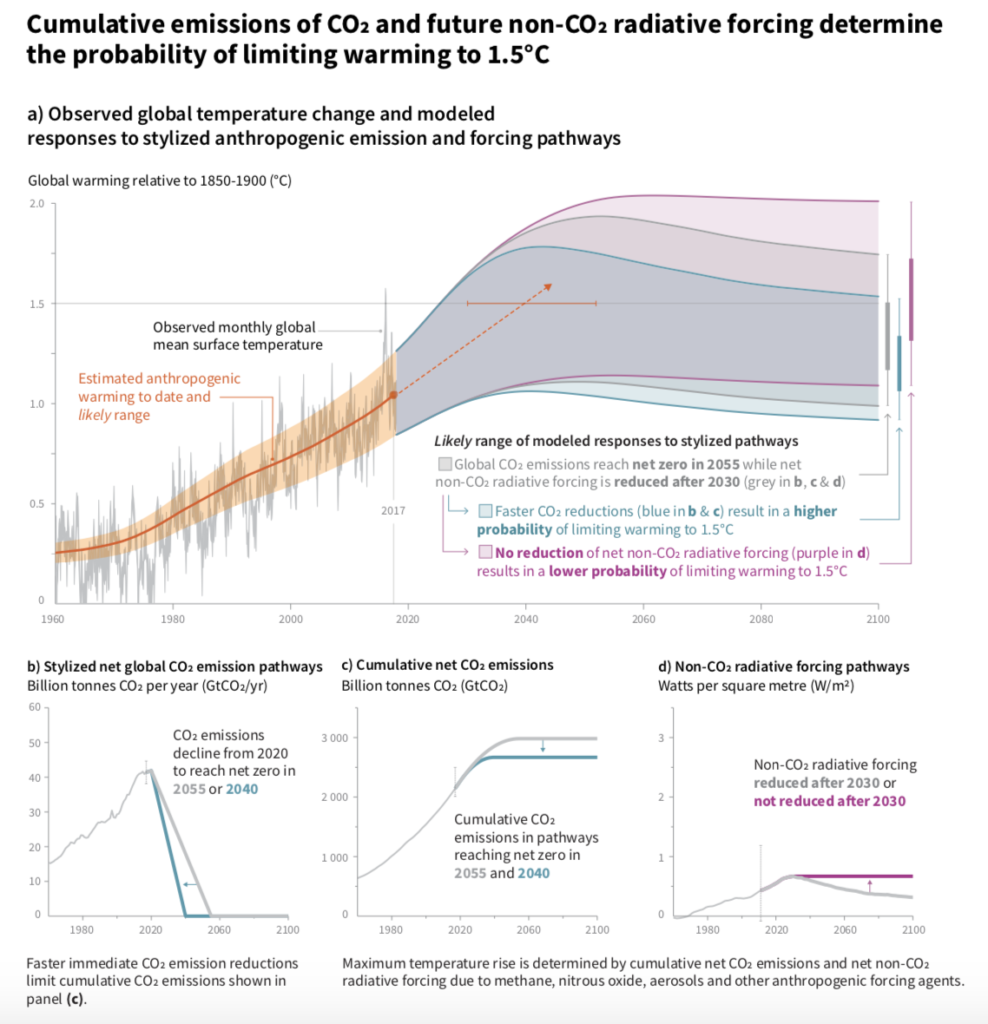

However, the science community is perfectly clear when it comes to interpreting ‘transformation pathways’. Chapter 6 of IPCC’s Working Group III’s contribution to AR5 and Chapter 2 of IPCC’s SR15 provide extensive discussion of the assumptions on which such interpretations are based. Here’s an image taken from the IPCC’s SR15 Summary for Policy Makers showing net zero pathways not for 2050 but for for 2055 and 2040:

There are a number of points to make here. The first is captured nicely in Ch2 of IPCC’s SR15: “Earlier assessments have highlighted that there is no single pathway to achieve a specific climate objective…Pathways depend on the underlying development processes, and societal choices, which affect the drivers of projected future baseline emissions” (p109). The second relates to trade-offs. “Transformation pathways inherently involve a range of trade-offs that link to other national and policy objectives” (AR5 WG III, Ch6, p420). The third relates to ‘feasibility’. While there are some science-based scenarios that clearly do make a certain outcome unfeasible (e.g. if you peak emissions too late and are entirely reliant on carbon dioxide reduction (CDR), but CDR is untested at scale or cost, then limiting warming becomes unfeasible), much like ‘credibility’, feasibility is first and foremost a political consideration:

“Statements about feasibility are bound up in subjective assessments of the degree to which other characteristics of particular transformation pathways might influence the ability or desire of human societies to follow them”

AR5 WG III, Ch6 p420

It’s also important to understand that the models on which transformation pathways and scenarios are based are, themselves, subject to numerous caveats and limitations. Chapter 6 of the AR5 WG III report describes these in some detail:

“Most fundamentally, integrated models are simplified, stylized, numerical approaches to represent enormously complex physical and social systems…The models do not structurally represent many social and political forces that can influence the way the world evolves…Instead, the implications of these forces enter the model through assumptions about, for example, economic growth and resource supplies…In this sense, the scenarios tend towards normative, economics-focused descriptions of the future”.

AR5 WG III, Ch6 p422

I hope that the above explains why science per se doesn’t support or imply a 2050 zero emissions target. There are other target dates besides 2050 and these, as with the 2050 target date itself, are influenced by social, economic and – perhaps most importantly – political factors. In the remainder of this post, I’d like to summarise the main objections to 2050 being the net zero target date. I divide these objections into two broad themes: the first relates to the limitations of the IPCC’s own analysis (which will be familiar to anyone with even a passing interest in this topic); the second relates to scientific analysis and observations since the publication of IPCC’s SR15 at the tail end of 2018 (which will be familiar to anyone who has read the news or simply looked out of their window recently).

Limitations within the IPCC’s analysis

It’s important to repeat that the IPCC didn’t review any zero model pathways “that achieve a greater than 66% probability of limiting warming below 1.5°C during the entire 21st century based on the MAGICC model projections” without recourse to some kind of carbon dioxide reduction (CDR) intervention – either by reforestation or employment of bio-energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) (IPCC SR15, Ch2, Table 2.1). These are not great odds in themselves – i.e. you role a dice and are only successful two out of every three throws. This is fine if you’re playing a board game; it’s not fine if the role of the dice determines whether or not the Earth careers into a hothouse state and irreversible global heating. If we want better odds, then we need to bring the zero emissions date forward.

It is crucial to understand that BECCS (bio-energy with carbon capture and storage) technology is still in its infancy. The IPCC concedes that “large uncertainties remain, in particular concerning the feasibility and impact of large-scale deployment of CDR measures” (IPCC 2018, SR15, Ch2 p121). An Editorial in Nature last year (which itself describes negative emissions technology as “magical thinking”) quoted the European Academies’ Science Advisory Council: “Negative emission technologies may have a useful role to play but, on the basis of current information, not at the levels required to compensate for inadequate mitigation measures.”

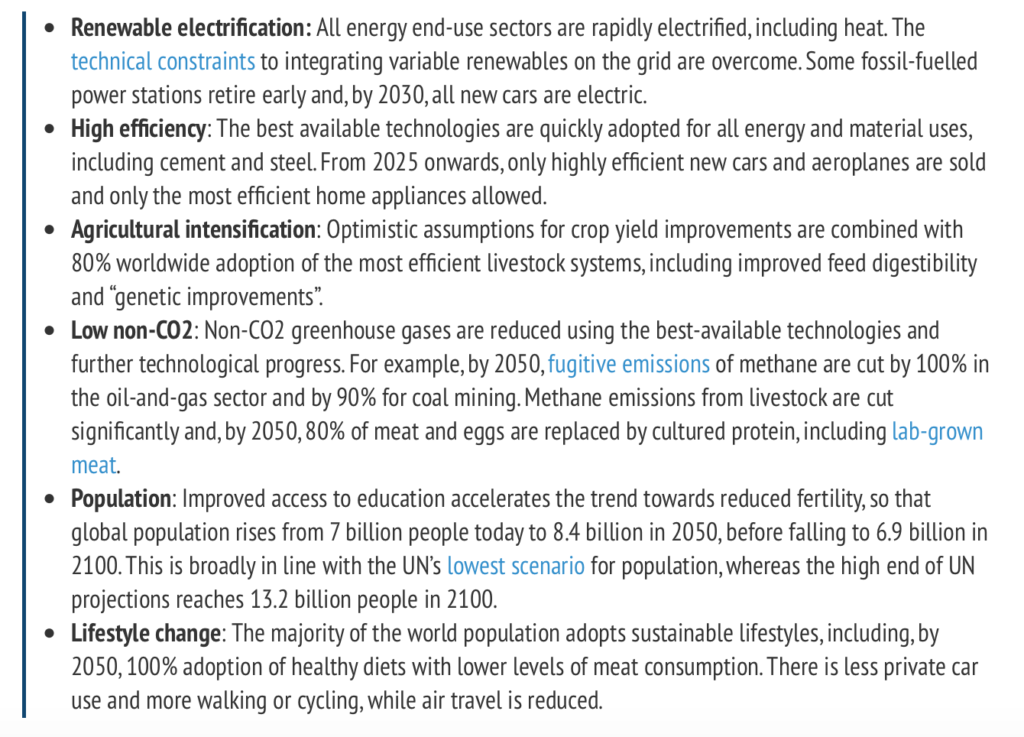

The CCC 2019 report is well-aware of the limited progress made in developing this technology, pointing out that in 2018 just 18 large-scale carbon capture and storage (CCS) facilities existed, globally. Wallace-Wells points out in his book The Uninhabitable Earth (and see his Guardian editorial) that we would need to open one and a half new plants every day for the next seventy years to limit global heating to 1.5 degrees. Recognising that “it will soon be impossible to achieve ambitious climate goals without implementing CDR to compensate overshoot of the carbon budget” Van Vuuren and colleagues in a study last year explored which aggressive policy options, if implemented, could decouple our reliance on BECCS. These are summarised below:

Alternatively, we could bring the zero emissions date forward. It’s curious, bordering on weird, how few Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) incorporate dates other than 2050. There may be an obvious reason for this but – disclaimer – I am not a climate scientist and the only models I work with on a regular basis are Lego. So if there is, do let me know. But going out on a limb, I would hypothesise that scientists working with IAMs are a conservative bunch, who work with socially constructed assumptions that have emerged within an equally conservative discipline (as per my discussion above). I imagine a conversation along these lines:

- Colin: Hey Janet, I see you’re working on your new IAM, cool! Ermm, what date are you using in your model?

- Janet: Oh, hi Colin. Thanks for asking. I thought I’d try 2025 for a change.

- Colin: Hilarious. But, really, which date?

- Janet: 2025.

- Colin: Are you crazy? You know what happened to Jethro!

- Janet: Oh, yeah [points to Jethro who is mopping the floor down the corridor]. So, you think I should, erm, change the date?

- Colin: [Rolls eyes] – duh, yeah-ur!

- Janet: 2030?

- Colin: Nope

- Janet: 204..

- Colin: 2050, 20 fucking 50! It’s always 2050!!

- Janet: Alright, [types 2050] keep your hair on. Sheesh.

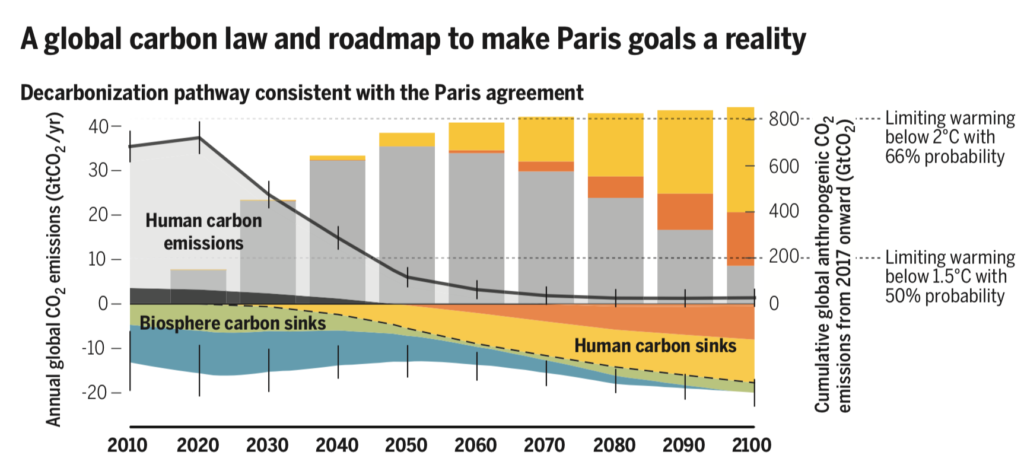

Consequently, 2050 is the date against which most scientists calibrate their models. I’m guessing. But that aside, without BECCS, the zero emissions date would have to be brought forward to the mid-2020s – so around the date Extinction Rebellion is calling for. It’s a busy figure, but see the image below from a study by Rockstrom and colleagues, and discussed further by Glen Peters here. The mid-2020s date is where the left hand point of the yellow ‘human carbon sinks’ band meets the horizontal zero emissions line.

Perhaps the most concerning limitation of the IPCC report is its reluctance to incorporate feedback loops (such as permafrost thawing) into its analysis (some may argue that this is a strength because the effects are uncertain and could potentially weaken an otherwise robust assessment). The SR15 report is upfront about this omission:

“The reduced complexity climate models employed in this assessment do not take into account permafrost or non-CO2 Earth system feedbacks… Taking the current climate and Earth system feedbacks understanding together, there is a possibility that these models would underestimate the longer-term future temperature response to stringent emission pathways”

IPCC 2018 SR15, CH2 p104.

Further more, although uncertain, the effect of feedback loops are estimated by the IPCC “to reduce the remaining carbon budget by an order of magnitude of about 100 GtCO2 and more thereafter”. The IPCC estimates our carbon budget with two in three odds of keeping below 1.5 degrees to be 420GtCO2 (it’s more for lower odds, i.e 580GtCO2 for one in two and 830GtCO2 for one in three). Take into account the feedback loops and the budget drops to 320GtCO2. We are currently emitting 42GtCO2 per year, so that gives us, hmmm, seven and a half years at current rates of emission. Bearing in mind that the report was published in 2018 and we are already half way through 2019 and emissions rates haven’t slowed, then we’re looking at 2025 to break through the 1.5 degrees threshold.

Observations since the publication of IPCC’s SR15 report

I think it’s fair to say that there have been some incredibly alarming reports this year. That the Greenland ice sheet is melting quicker than scientists predicted is an issue etched into the brain of anyone who saw Stefen Olsen’s mind blowing photograph on Twitter a couple of weeks ago.

Earlier this year Bevis et al 2019 found a 4x increase in the rate of ice melt between 2003 and 2013 “due to the combination of sustained global warming and positive fluctuations in temperature and insolation driven by the NAO”. Rignot et al 2019 reported that the Antarctic lost 252Gt ice between 2009-2017, up from 40Gt during the 1970s. Last week, Damian Carrington reported in The Guardian on the doubling of glacial ice melt in the Himalayas since 2000 – up to 8Gt per year – with global heating the primary cause. In case you’re wondering, a Gt = a billion. You could probably fit a tonne of ice into your car. Times that by a billion, and then times that by 252. That’s how much ice is melting into the sea every year just from the Antarctic ice sheet.

What effect do you think that’s going to have on sea level rise? For years climate scientists like Paul Beckwith have been warning of 5-10 feet increases by mid-century. In the video link, he notes that conservative estimates of the current (but exponential) sea level rise of 3.4mm per year, which would result in a 3-4 feet rise by 2100, are likely to be reached by mid-century. Alarmist? Well, the BBC covered this issue in May this year, reporting on a new study that anticipates a 2m rise by the end of the century (that’s about 8 feet, incidentally).

The point I’m trying to make is that scientists are being consistently surprised – in real time, it seems – by events playing out before our eyes. How many times have you heard or read statements from scientists working in various climate-related fields along the lines of ‘we weren’t expecting this!’, or ‘it really took us by surprise when we found that!’? Again, that’s fine if the ‘that’ is a new species of mollusc or a lost Alan Bennett script, but definitely not fine if it’s an unprecedented species extinction rate. I focus above on ice melt but I could just have easily chosen something else. Here’s Dr. Roisin Commane describing her findings on permafrost thaw in the Alaskan Tundra: “We’re seeing this much earlier than we thought we would see it.” ‘This’, by the way, refers to the somewhat worrying finding that “Alaska, overall, was a net source of carbon to the atmosphere during 2012–2014” completely overwhelming “a small net uptake from boreal forest ecosystems”. Elsewhere, in Siberia, scientists are reporting a warming of almost 1 degree C in permafrost 30 feet below ground. As Romm puts it: “Humanity is leaving the freezer door wide open”.

The CCC report – 2050 is too late!

So we have a report that makes the case for the UK to achieve zero emissions by 2050. That target has now been enshrined in UK law, to almost universal applause. But, pace universal applause, this is misplaced. The report adds the following caveat to its analysis: “If replicated across the world, and coupled with ambitious near-term reductions in emissions, it would deliver a greater than 50% chance of limiting the temperature increase to 1.5°C” (CCC 2019, p11). Are those odds good enough for you? And recall that the reason why “delivery must progress with far greater urgency” is because – in the decade since the last piece of climate legislation – “current policy” has been “insufficient for even the existing targets” (of 80% emissions by 2050) (CCC 2019, p11). That is a pretty damning track record.

This isn’t the post to relate all the emissions-heavy projects the UK government is currently supporting and which aren’t consistent with a net zero strategy, so I’ll park that for now on runway three. Neither is this the post to reflect on the UK’s consumption emissions (which are 69% greater than its territorial emissions) an issue the CCC report duly notes and discusses in its report: “Estimates published by Defra…indicate that UK consumption emissions were significantly higher than comparable territorial emissions reported in the UK GHG inventory. That reflects the high carbon intensity of our imports” (p105 and Box 3.3). This also isn’t the post to push back on the reliance in the report on greenhouse gas removal via direct air capture of CO2 with CCS (DACCS), enhanced weathering and biochar, not to mention BECCS. And, finally, this isn’t the post to critique the argument presented in the report that “the UK has continued to demonstrate that it is possible to decouple emissions growth and economic growth” (p46). These will have to wait for another time.

I’ll end this post with a couple of quotes and a figure. I think the IPCC is spot on when it says:

“Ultimately, society will adjust the choices it makes as new information becomes available and technical learning progresses, and these adjustments can be in either direction…Societal choices…may also influence what futures are envisioned as possible or desirable and hence whether those come into being”.

IPCC 2018, SR15 Ch2 p99

On the one hand, I take inspiration from that because I am part of a climate movement that is trying to influence the future by creating possibilities that didn’t exist before. In one respect, the CCC report is also trying to create possibilities – we now have a country that is aiming for net zero emissions! That is a first – hence the applause. But what possibilities have now been sidelined as a consequence of that report, and subsequent legislation? The report effectively silences any more radical – but necessary – net zero emissions targets. 2040? No chance. 2025? Forget it.

The IPCC again: “Earlier scenario studies have shown, however, that deeper emissions reductions in the near term hedge against the uncertainty of both climate response and future technology availability” (SR15 Ch2 p99). Our number one priority must be to peak emissions immediately and reduce emissions to zero as quickly as possible. But how quickly is possible? The CCC report doesn’t discuss that; it doesn’t present a range of options for us to choose from; indeed, despite claims to the contrary, it doesn’t countenance any other date than 2050 – which is presented as the only “credible”, “feasible” and “realistic” date imaginable. We must do better than that. Or that figure – 2050 – will be the death of us.

Andrew

Awesome work and communication of the nexus of science and social policy. Glad I have stumbled upon this, via a Kate Raworth Tweet I think. Submission deadline for the NZ “Climate Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019 is on 16th July. Than you Andrew for clarifications of the fit for purpose parameters , the Goal (66% confidence, not “2050” ) and the need for system regulatory integrity that is constantly responsive to evidence of both climate science, policy performance and social license for risk settings.

Thanks very much Alistair! Kate’s tweet really helped get this post to a wider audience – such is the power of Twitter! Glad you got something positive out of the post. I hope it feeds in to the submission in some way.